The Mountains (2023) ‘Sheffield Docfest’ Review: Christian Einshoj’s directorial The Mountains is a film that aims to bridge an emotional distance within his family. The defining locus in their lives has been the death of Einshoj’s younger brother, Kristoffer when he was a kid. No one has quite recovered from that episode and has resisted sharing and exchanging their experiences on how it has altered their lives irrevocably. The scars are palpable in the ways Einshoj’s father, Soren, and his brothers chose to subsequently steer their trajectories.

Everyone went their separate ways, seeking ways of escaping the damage wrought on their emotional lives, skirting a connective, mutual space of dialogue wherein a process of substantive healing and trauma-redressal could have been affected. Their unspoken decisions to duck any such communicative recovery stretched and exacerbated the deepening split within the family to a degree where Einshoj, in a telling scene, himself does not quite know how to grapple with his brother’s sudden confession of suicidal ideation. He stops filming, assuming it could possibly impede subsequent intimacy of the particular moment, but finds himself unable to comfort and assuage, both lapsing instead into an awkward hug-less silence and, soon, he realizes the moment of his unburdening has already passed.

The film mines the depth of mute denials and evasions with which the family has handled Kristoffer’s death, which they had been preparing for ever since the treatments began, and the doctors stipulated the time he had left. Einshoj chiefly draws upon the astonishing archive of their home videos, compiled over a twenty-five-year span, using his own narration for most of the film. Therefore, much of it is his private reflection on his family’s evolving moods through the decades, relayed over the rigorously documented events, both big-occasion and the every day, that they have shared or experienced in isolation.

After they get to know Kristoffer has a week to live, Soren buys a camera and starts relentlessly recording as much as he can as an act of preservation. The family originally shifted from their native Denmark to Norway for Soren’s job. The treatment complications prolonged the stay, and they became pretty much rooted in Norway thereafter. When the film opens, Einshoj, thirty-two, returns home to meet his family after a year because of his dad’s sudden decision to sell his house and move back to Denmark.

He views this as a moment at which his family can dissolve, and he feels compelled to intervene as subtly as he can, which he regards as the essential digging into the profound, silently stormy emotional trail the death left in its wake. Soren never stopped moving thereafter. Choosing to get thoroughly consumed by work, he took frequent global tours, never keeping himself tied to one place. Einshoj admits he once wished he had a mustache like him and a business card.

After the death, his father withdrew to filming on his own, filing away the tapes. Einshoj delves into them, initially suspecting them of holding traces of his dual life or some illicit affair. What emerges are hour-long videos of birds of various plumage, captured with unwavering patience and reverence. In a striking line, Einshoj acknowledges that it is in these bird videos he feels closest and most intimately connected to his father. There is a startling vulnerability his father expresses through these videos that Einshoj wishes he didn’t feel the need to repress.

The Mountains plays out as a quest for these hidden inner lives, the secret selves which Einshoj pursues. In the knowing, in the slow extraction of their traumas, he hopes to lay the road to retrieval, a renewal of stability long foregone after the death. His brothers, Frederick and Alex, demonstrate similar patterns of self-destructive, reckless behavior fifteen years apart. Both have drifted away once deeply close to Einshoj, Frederick receding into an emotionally locked silo. Expression of his vulnerability and grief became immanently linked to how he perceived conventional, normative masculinity.

Once remarkably uncynical and bursting with life, he turned guarded and obtrusively taciturn. Einshoj riffles through the footage of their childhood for clues that can prime him to that turning point of his transformation but soon discovers the futility of that pursuit. The images of him from fun rides at parks and fairs and singing Christmas carols constantly reaffirm a jovial presence, foiling his anxious search. For the director/narrator, the camera’s capturing is embedded with a function of bonding as well as a source of personal solace. The camera was once a tool to bring Einshoj and Alex together, enabling their intimacy, but the relationship gradually froze.

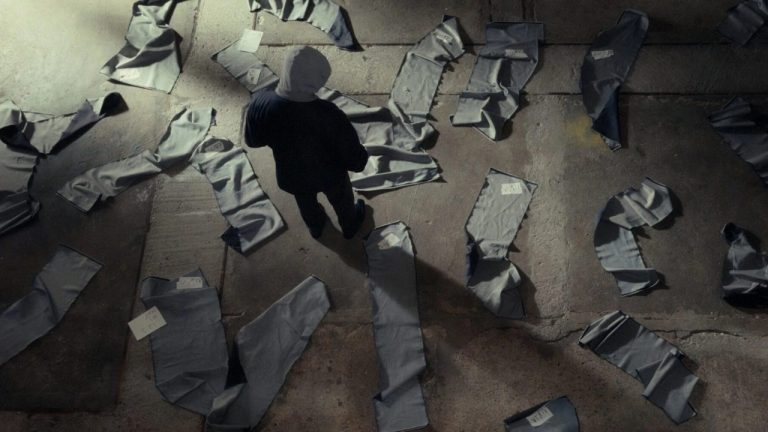

The montage of the brothers’ reconstruction of their childhood hobby of superhero-channeling, with the Norwegian mountains at their back, has a heart-warming, organically fused force to it that gathers all the emotional stakes built in the journey so far. The director gently unpeels cross-generational masculinities and male vulnerability shared between the father and brothers in their respective privation.

Initiating a tussle between withholding and revealing, the film could have loosened up a little without the overbearingly constant voiceover. Still, Einshoj deftly approaches the delicate nature of male silence, their unease with articulating grief publicly and openly, and that nagging feeling of being disconnected from one’s family, which drives the sense of estrangement deeper. This is a charmingly modest film, aware of the limits of its confessional mode while scooping out truth and honesty from within.

![Just Like That (Aise Hee) [2019]: ‘MAMI’ Review – The Unattractive Reality of Small-Town Existence](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/just_like_that01_copy-768x433.jpg)

![The Looming Storm [2018]: ‘NYAFF’ Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/THE_LOOMING_STORM_HOF-768x512.jpg)