Aisha Osagie is a young Nigerian woman who is seeking asylum in the state of Northern Island. She finds herself in the asylum system, almost in suspended limbo—allowed to stay in the country but only in designated locations, following a curfew and rules—but not allowed to fully integrate into society. As Aisha states at the end of the film, she isn’t expecting a handout in one of her innumerable trials for appealing to be given asylum.

And perhaps that’s where the Matt Berry-written and directed film truly succeeds—in highlighting the dignity of a woman who is faced with casual racism, sexism, and limited knowledge about the linguistic varieties in her own country, on top of the bureaucracy. It’s almost darkly hilarious how, in her job as a hairdresser, one of her customers remarks that her English is good, and a couple of scenes later, we see Aisha describing to her new-found friend Conor in detail the vernacular and dialect differences of English with Nigerian and Irish affectations.

The movie, though, is all about the rigor and intricacy of bureaucracy pushing the very people the system had been ostensibly designed to help in the first place. It is a system so constricted and so overtly concerned with rules that basic tenets of empathy are easy to shrug off but valuable to be elicited out of, empathizing and, as a result, even exploiting trauma to ensure the interviewers are “put in the room” to understand the gravity of Aisha’s situation. It’s clever screenwriting as well because it makes Aisha’s guardedness both poignant and yet eerily compelling.

She reveals her past in patches of information when asked and only reveals essential bits. Her guardedness stems from her reluctance to be vulnerable and relive the trauma. It culminates in one of those patented interview scenes placed squarely in the middle of bleak conversational dramas, where the revelation of the character’s past or the inciting incident almost threatens to boil over. Except here, Wright, as Aisha, is fully in control, or at least capable of showing Aisha holding back from falling apart.

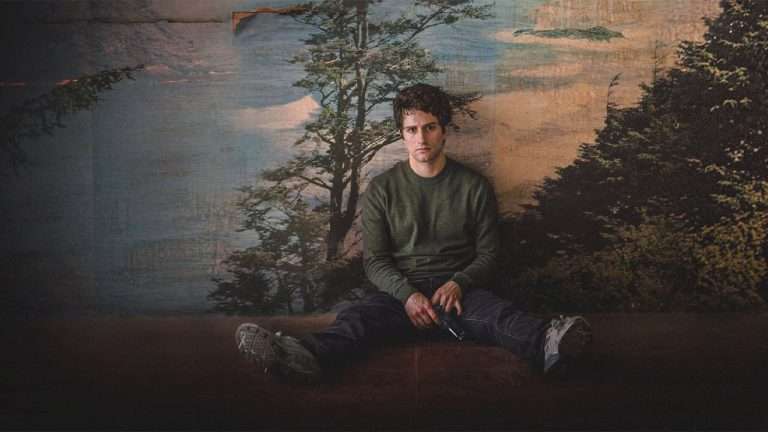

This is the Letitia Wright show, through and through. She is there in the frame for every second of the film, and she displays a chameleonic-like quality in understanding the vision of the director. For movies dealing with dramas about the byzantine nature of immigration and bureaucracy, it is perhaps hard to deny the temptation to go full-bore kafkaesque. But Berry foregoes surrealism instead of going for a kitchen sink, almost docufiction-like outlook in terms of aesthetics as well as storytelling.

He has a perfect partner in Wright, who understands the exact gear to play the role. Wright manages to evoke the quiet strength as well as the frustration stemming from Aisha through every jaw-clench. Considering what the story puts her through—being shifted from her place twice, having to look for jobs, being refused permission to leave the country to attend her mother’s funeral—unless she admits to that journey being a voluntary one, It is perhaps not a surprise that when the break happens, it begins with Aisha punching the wall of the movable home before almost tearing herself through a rampage.

Amidst it all, her one ray of light is the odd friendship she strikes with Connor, the new security guard working the night shift at the first place we first see her living. There is an easygoing chemistry there, an awkwardness between the two that feels organic rather than exaggerated. However, due to the nature of the story, watching the protagonist’s misery pile on, and that too in the most understated fashion, makes for a tough and even a staid watch at times.

The respite comes from brief snatches of happiness amidst the sea of dour moments, but the movie doesn’t have any such moments to give a sense of breathing room. This solipsism also makes the film’s world seem underdeveloped because everything revolves around Aisha’s orbit. The movie does take a gingerly step in developing Connor’s backstory slightly, emphasizing how life in prison does make him sympathetic to Aisha’s plight. There are also slight filmmaking choices in how Aisha first chooses to open up to Connor, and later Connor opens up about his feelings, both shot almost like inverse scenes of each other.

Subtle, bleak, and understated almost to a fault, Aisha doesn’t relentlessly pile on the bleakness, but it never loses sight of the reality of the helplessness faced by scores of people like Aisha in immigration systems in parts around the world. The movie ends without compromising an ounce of that bleakness, but it does end with the camera focusing on Wright’s face as she recovers from another setback, steels herself, and moves forward. It leaves you with a little kernel of hope, and really, isn’t that what most people truly operate on?