Maybe we don’t always prioritise others, but that doesn’t mean we always go unnoticed. Aloners (2021), a 90-minute Korean drama, offers a quiet yet profound meditation on isolation, grief, and mostly on human connection. Directed by Hong Sung-eun and starring Gong Seung-yeon, the film follows Jina, an experienced call-centre employee for a credit card company, as she navigates her monotonous daily routine.

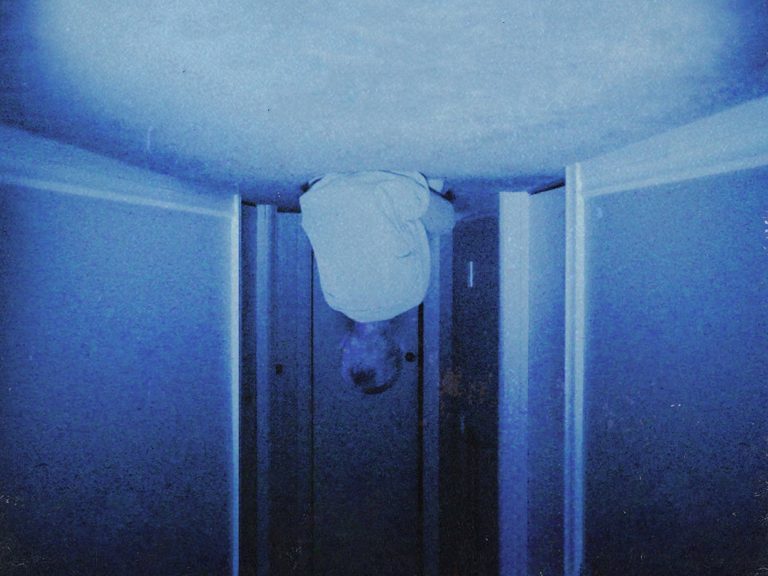

She wakes up after yet another sleepless night, commutes to work by bus, takes her scheduled cigarette breaks with robotic precision, eats lunch alone, and returns home—always on the same bus, often in the same seat. Every action is performed with a near-mechanical detachment, her face a blank slate devoid of emotion. What remains clear is that she is alone—at home, at work, during her commute, in every aspect of her life.

The film slowly peels back the layers of Jina’s life, revealing the deep-seated grief she carries. Her mother’s death has left a void that she hasn’t been able to fill, not even with her estranged father, who himself struggles between partially mourning his late wife and partially showing a strange excitement over her remaining will. Their relationship is distant, fragmented, and filled with unresolved mysterious emotions.

Once separated from Jina’s mother for not 20 years, but 17 years, her father reunited with her only a couple of years before her passing. While her father may be coming to terms with the rekindling of an old connection that ended too soon, Jina feels a different kind of loss—one that is far more profound. His wounds of separation do not compare to the deep, unresolved grief that lingers in his daughter’s heart.

Rather than confronting her emotions, Jina buries herself in work, earning recognition as a top employee—amid mental trauma. Perhaps isolation isn’t new to her and solitude comes naturally, helping her function in an ordinary life, or maybe her diligence at work is an unconscious coping mechanism. This level of confusion about Jina’s emotions is what we as an audience could experience in the first act.

Jina likely shared a close bond with her mother, but the film offers us only the aftermath of her loss. A woman who has lost her mother now unexpectedly finds herself in a maternal role—guiding a young intern at work. This subtle shift in her routine hints at an emotional undercurrent she cannot yet acknowledge. In parallel, another disruption shatters Jina’s carefully constructed solitude—the sudden death of a neighbour. The shock isn’t just for Jina—it’s for the audience as well. What she once perceived as a casual, distant presence in her surroundings turns out to be merely a memory of a person she had overlooked. Caught in the repetitive loop of her daily life, she failed to notice the small, yet significant, changes around her—just as others may have failed to notice her.

Also Read: The 10 Best Korean Movies on Prime Video

The film masterfully plays with irony through the characters surrounding Jina. The intern, for instance, is young, energetic, and completely opposite of Jina—she cannot bear to be alone. Meanwhile, Jina is a professional “Aloner”. She declines to participate in her mother’s memorial, a gathering organised by her father with neighbours and members of the church, including an important minister.

And yet, in a twist of fate, Jina finds herself attending her neighbour’s memorial instead. The young intern, the deceased neighbour, the injured new tenant in her apartment building, her pragmatic father, her long-time boss, and her once-loving mother—each of these figures leaves an impact on Jina’s life. And as the film progresses, we are left with Jina’s internal journey.

The silent ache for emotional bond from another human being is lost in translation. Jina is continuously surrounded by non-living things that always keeps her engaged and distracted including the computer she uses for the work, the TV she barely watches but always keeps on, the phone she uses to watch reality shows—an escape from the reality and the CCTV to revisit the last moments of her mothers, the duality of her father’s emotions.

Jina is resistant towards letting new people into her life; not a stranger, not a long-known boss who is also a friend, not even her father. The act of forgiving and apologizing to others takes nothing but an effort that brings kindness and respect towards each other. This strikes Jina’s mind, when she finally realizes why the intern quit the job. Sometimes it is important to acknowledge someone’s care, and sometimes we have to be careful with the words that come out of our mouths, while going through tough times—this perfect balance in the writing might be easy to come up with but adds essence to the story.

“Aloners” is a slow-burn character study, quietly dissecting the weight of grief, isolation, and the subtle ways in which people intersect—even in solitude. It’s a haunting reflection on modern loneliness, reminding us that even in our most isolated moments, we are never truly invisible. Gong Seung-yeon delivers a stunningly restrained performance, her expressionless face and lethargic actions perfectly embody the emotional numbness of her character. Other actors were brilliant enough to add more depth to Jina’s character. Gong Seung-yeon’s portrayal is hauntingly real, allowing us to feel the weight of Jina’s solitude without the need for dramatic dialogue.

Cinematically, the film’s editing choices are worth noting. Some sharp, abrupt cuts in the beginning reflect the rigid monotony of Jina’s life. However, as the film progresses, we see longer takes, subtly allowing space for emotions to seep in—mirroring Jina’s slow transformation. The shots were mostly fixed and repetitive angles, one more subtle way of capturing the same pattern of life. We could not stop thinking about the end of the film, how the protagonist is going to reflect upon her loneliness. But even so, “Aloners” stands out—not by offering grand revelations, but by capturing the realistically quiet and aching reality of modern solitude and grief.

![Riceboy Sleeps [2022]: ‘TIFF’ Review – A Deeply Personal Take on a Family Running Deep](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Riceboy-Sleep-2022-Movie-Review-768x384.jpg)

![The Dose [2020]: ‘Fantasia’ Review – A slim story anchors an engaging directorial debut](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/The-Dose-La-Dosis-Movie-Review-highonfilms-3-768x414.jpg)