Stanley Kubrick, a filmmaker renowned for his exacting precision and deep thematic exploration, delivered one of his most visually stunning and narratively subtle works with “Barry Lyndon” (1975). Based on William Makepeace Thackeray’s novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon, the film traces the rise and fall of an ambitious Irishman, Redmond Barry, as he navigates the 18th-century European aristocracy. Though “Barry Lyndon” is often overshadowed by Kubrick’s more famous works like “2001: A Space Odyssey” and “A Clockwork Orange,” it stands as an intricate study of human nature, societal ambition, and the consequences of vanity—all wrapped in a visually arresting package, and is my personal favorite of Kubrick’s work.

The plot of “Barry Lyndon” revolves around Redmond Barry, a young man from rural Ireland with dreams of climbing the social ladder. After a series of events—including a duel, a stint in the military, and a marriage to a wealthy widow—Barry finds himself entwined in the European upper class. His journey is both fascinating and tragic. Barry is a man consumed by ambition, seeking both wealth and status in a world that seems to reward those born into it rather than those who claw their way in.

Kubrick presents this narrative in a way that distances the viewer from traditional emotional engagement. There’s a cool detachment in the storytelling, which mirrors the protagonist’s own detachment from the world around him. “Barry Lyndon” does not offer the kind of character-driven emotional arcs that are commonplace in many biographical dramas. Instead, Kubrick presents Barry as an observer of his own life, with his moral failings and emotional shortcomings gradually becoming evident but never fully explained.

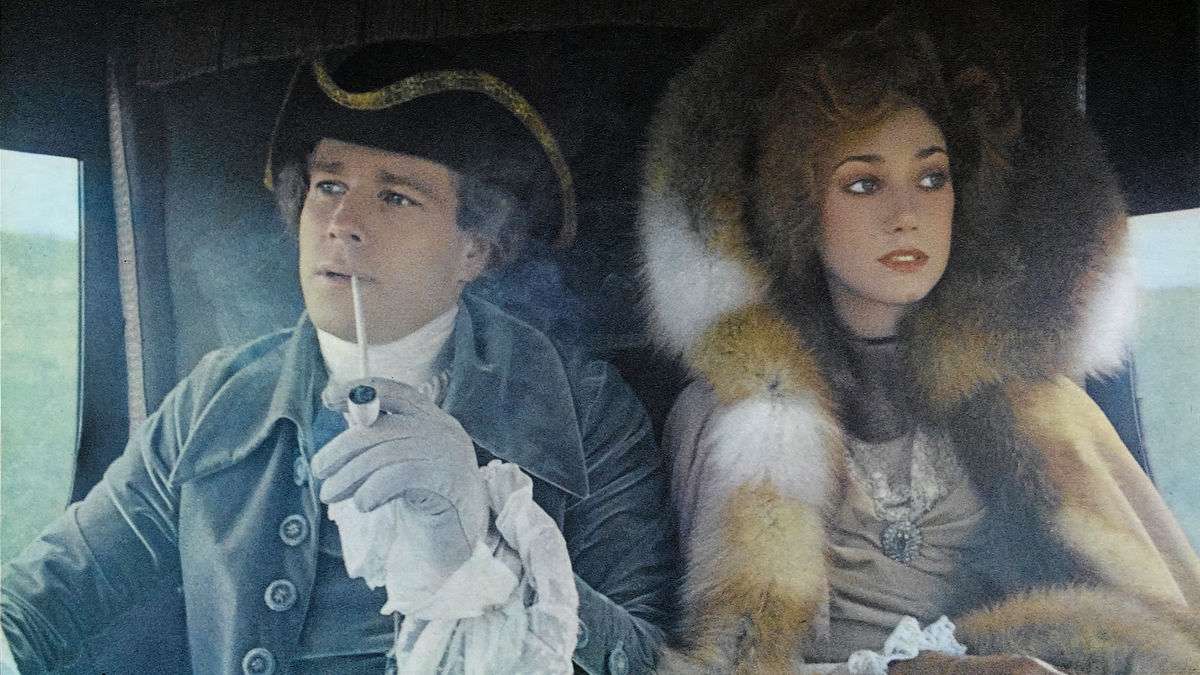

While Kubrick’s films are often associated with groundbreaking themes and innovative storytelling, Barry Lyndon” distinguishes itself with its breathtaking visual style. The film is a visual meditation, often compared to a painting come to life. Kubrick’s meticulous attention to detail and his collaboration with cinematographer John Alcott resulted in an aesthetic that is both historically evocative and highly stylized.

One of the film’s most famous features is its use of natural light. In a groundbreaking achievement, Kubrick and Alcott utilized lenses capable of shooting in extremely low light, allowing them to capture scenes by candlelight with a level of clarity previously unseen. This choice not only added an air of authenticity but also brought out the luxurious textures of 18th-century settings and costumes, adding depth to each frame. The candle-lit scenes, in particular, evoke the painterly quality of the time period, making the film feel like a living oil painting.

Moreover, Kubrick’s use of symmetrical compositions and slow, deliberate camera movements contributes to the film’s sense of stillness, as though we are gazing at a series of meticulously arranged moments frozen in time. Every frame is a work of art, each scene a reflection of the social order that Barry seeks to conquer and ultimately fails to understand.

At its core, “Barry Lyndon” is a critique of social mobility, ambition, and the consequences of pursuing a life of wealth and status without understanding the human cost. Barry’s journey is one of continual self-destruction. His relentless pursuit of an idealized life—a life of aristocratic privilege and financial security—ultimately leaves him alienated and broken.

The film makes it clear that Barry’s rise is not a result of his own virtues or moral fortitude but of circumstance and luck. He is manipulated by those more powerful than him, and his moral decline mirrors the world he inhabits—one defined by vanity, social pretensions, and an unyielding pursuit of status. In the end, Barry’s ascent feels hollow, a painful reflection of the empty nature of social hierarchies.

The film’s classical score further complements its visual and thematic richness. Composed of works by composers like Handel, Schubert, and Bach, the music reflects the time period and also serves as a commentary on the grand themes of the story. The use of the waltz, for example, in pivotal scenes is both a nod to the aristocratic world Barry seeks to enter and a tragic symbol of the emptiness of that world. The music provides a sense of grandeur and inevitability, echoing the rise and fall of the protagonist while reinforcing the film’s sense of fatalism.

“Barry Lyndon” is a film that demands patience and careful attention. Kubrick, never one to shy away from intellectual and artistic ambition, presents a work that is simultaneously beautiful and tragic, calm and suffocating. It is a meditation on the nature of ambition, the cost of societal success, and the futility of attempting to control one’s fate in a world where luck, birth, and death often have the final say. The film is a rich tapestry of visual splendor, philosophical musings, and complex character study—a rare work of art that transcends its period setting and speaks to universal truths about human nature.

In the end, “Barry Lyndon” invites contemplation. While it may not have garnered the same level of mainstream success as Kubrick’s other masterpieces, it stands as a quietly profound and visually arresting exploration of the fragility of human aspirations set against the opulent but decaying backdrop of 18th-century Europe. It is a film that stays with you long after the credits roll, much like the rise and fall of the man it portrays.

![The Beach Bum [2019] Review – Freewheeling Poetry of the Excess](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/The-Beach-Bum-highonfilms-768x432.png)

![Time of Moulting [2020]: ‘Nightstream’ Review – A slow burn mood piece too prescient for its own good.](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Time-of-Moulting-highonfilms-768x432.jpg)