From the early stages of film history, two broadly contrasting factions of filmmakers can be identified based on their approach to film aesthetics. The first group, which placed their faith in montage, can be classified as formalists, while the second group, which emphasized a more realistic representation of the world, can be classified as realists. Early film theorists sought to establish cinema as a legitimate art form by emphasizing its capacity to deviate from the real world. They argued that cinema had the right to diverge from reality in order to distinguish itself as an art form that evokes a subjective sense of the real.

Early filmmakers like Georges Méliès can be seen as one of the proponents of this notion, as their films delve into fantasy worlds that have little in common with the real world, often structured in an episodic manner, with separate images stitched together through editing. Later, when Soviet film theorists began to theorize montage, they used this extensive form of editing to, as André Malraux put it, “give birth to film as an art, setting it apart from other art forms, and creating a language.”

However, from the very beginning, cinema also held the potential to capture the real. A famous example of this is the incident in which audience members allegedly ran out of the theatre after seeing the Lumière brothers’ “The Arrival of a Train” (1896). Realist film theorist André Bazin highlights that the real is, in fact, a core asset of cinema. It is the “real” that is a prized possession of the medium. In contrast to the montage theory, Bazin argues that montage restricts the objective possibilities of the film image by imposing a predetermined dramatic logic on it.

He states, “It is the logic that conceals the fact of the analysis, the mind of the spectator quite naturally accepting the viewpoints of the director, which are justified by the geography of the action or the shifting emphasis of dramatic interest.” This can be illustrated by the famous experiment conducted by Lev Kuleshov, where the actor Mozhukhin’s face was shown in succession with different images: a dead child, food, and a lady. Each combination evoked a different meaning: Mozhukhin with the dead child evokes pity, Mozhukhin with food evokes hunger, and Mozhukhin with the lady evokes lust. These combinations emphasize the subjective nature of the dramatic logic imposed by the director.

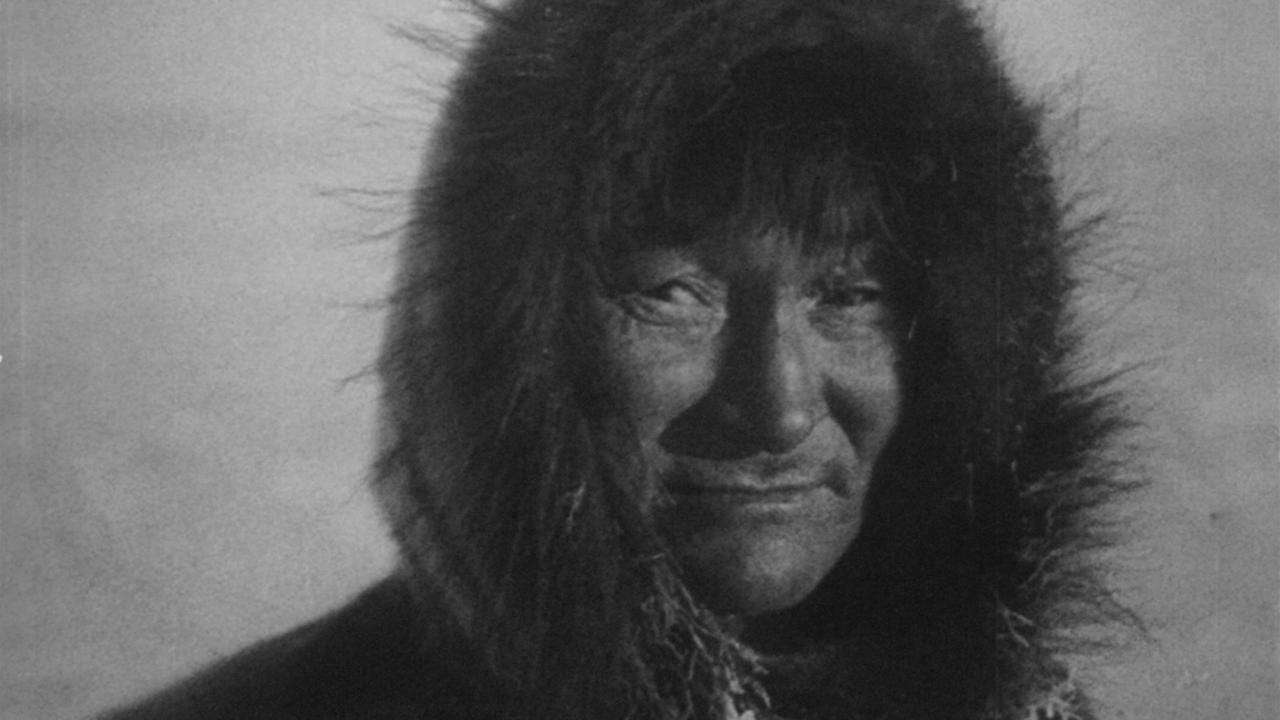

Bazin’s approach to realism draws our attention to the fact that while montage takes us on a journey, it is a guided journey. In contrast, there is another type of journey that can occur if filmmakers place their faith in reality. For instance, Bazin discusses the famous seal hunting sequence in Robert Flaherty’s “Nanook of the North” (1922), noting that, “What matters to Flaherty, confronted with Nanook hunting the seal, is the relation between Nanook and the animal; the actual length of the waiting period.

The montage could suggest the time involved. Flaherty, however, confines himself to showing the actual waiting period; the length of the hunt is the very substance of the image, its true object.” In simpler terms, Flaherty’s refusal to cut creates both spatial and temporal continuity between the real and the reel. The time that Nanook waits on screen is identical to the time the audience waits in reality. As cinema evolved, Bazin noted that filmmakers began to use deep focus and long takes to achieve a sense of harmony between space and time, creating a language of cinematic realism. This became the foundation of ‘Bazinian Realism’.

While many filmmakers have employed this technique to varying degrees, only a few have fully embraced ‘Bazinian Realism’ and even sought to push it further. Filmmakers such as Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Nuri Bilge Ceylan have repeatedly and imaginatively explored the aesthetic potential of the long take in their works. However, none of them can be said to fully follow the principles of ‘Bazinian Realism’ in its purest sense. For instance, Brian De Palma is one of the great long-take directors, frequently using the Steadicam to track complex spatial arrangements, but he is also known for his expressive use of montage.

Tarkovsky, on the other hand, relies on dreamy imagery, episodic narratives, and non-linear editing, adopting a more formalist approach. And, in the case of Scorsese and Ceylan, long takes are often used to emphasize the characters’ subjectivity. In contrast, Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón’s work demonstrates a particular fixation on the capacity of the image to display more complex indices of time and space. Scholar Bruce Isaac notes that the aesthetic disposition in films like “Y Tu Mamá También” (2001), “Children of Men” (2006), and “Roma” (2018) is grounded in the uninterrupted flow of time and space, a characteristic that reflects the cinematic approaches of neorealist filmmakers and the works of Orson Welles and William Wyler in the 1940s.

In his canonical essay, “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” Bazin examines how filmmakers manage to evoke realism using long takes and deep-focus cinematography. He proposes three psychological modalities that relate to this aesthetic approach. First, Bazin notes that “the depth of focus brings the spectator into a relation with the image closer to that which he enjoys with reality.” This means that, regardless of the content of the image, the structure itself feels more real. Second, in contrast to montage, deep-focus cinematography puts everything in focus, avoiding the omission or emphasis of certain elements.

Whereas montage directs the audience’s attention, deep focus allows the viewer to choose where to focus. As Bazin writes, “It is the form of his attention and his will that the meaning of the image in part derives from.” Third, Bazin argues that deep focus and long takes propose a sense of ambiguity in the image. While montage creates a spatial and temporal arrangement that is clearly visible to the audience, deep focus opens up the image to a metaphysical exploration that reintroduces ambiguity. Rather than providing a clear, predetermined meaning, this approach invites the viewer to interpret the image on their own.

When analyzing the films of Alfonso Cuarón—particularly “Y Tu Mamá También,” “Children of Men,” and “Roma”—we can see how Cuarón embraces ‘Bazinian Realism’ and takes it further. Cuarón, along with his cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (who worked with him on “Y Tu Mamá También” and “Children of Men”), employs various long-take techniques across these films.

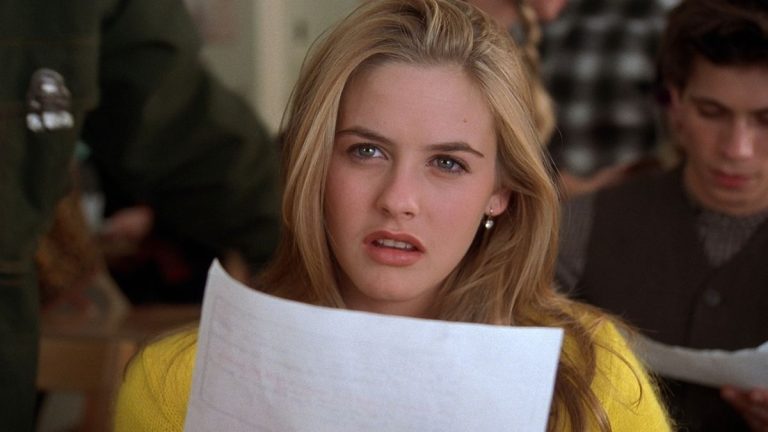

In “Y Tu Mamá También,” a road movie about two young boys, Julio and Tenoch, who invite an older woman named Luisa to join them on a trip to a fictional beach called “Heaven’s Mouth,” the film uses numerous “unobtrusively long takes,” as Peter Bradshaw puts it. One of the opening sequences introduces Tenoch through a series of long takes in a single room, where the camera moves freely and holds the action long after the viewer might expect a cut. Bruce Isaac argues that the camera in “Y Tu Mamá También” is imbued with the capacity to move where it chooses, depicting both the background and foreground in concert, erasing the traditional perspectival hierarchy of objects within the spatial field.

The frame is held in a medium-long shot, yet it is never stable; it is never an objective shot depicting the narrative action of a sequence. The result is an impression that the story is unfolding from the audience’s point of view. This cinematography creates an illusion where the audience feels omnipresent, “bringing them into a direct relation with the image closer” (the first point of ‘Bazinian Realism’).

However, the most striking aspect of the film is that the camera frequently shifts its focus away from the central characters to the background. This technique expands the scope of the film’s narrative to include a broader political and historical context. Julio and Tenoch pass through a period of political transformation in Mexico, and while the boys are unconcerned with the political environment, the camera allows us to observe the complex spatial field of protesting bodies. Isaac argues that the camerawork in “Y Tu Mamá También” encompasses separate narrative frames—the boys’ road trip and the political demonstration—and integrates them within a singular spatial and temporal whole, moving between the two without interruption.

The long take here serves as a form of spatial revelation, presenting foreground and background not as discrete frames, but as a unified, “acculturated” whole. As Isaac notes, the camera, fixed in its movements to the body of the operator and drawn increasingly to the crowd, documents the narrative diegesis while revealing the historical past in the present, implicating the road trip narrative as merely one (and not necessarily the primary) affective field. This long take strategically documents the narrative while simultaneously presenting a larger, more complex historical reality to the viewer.

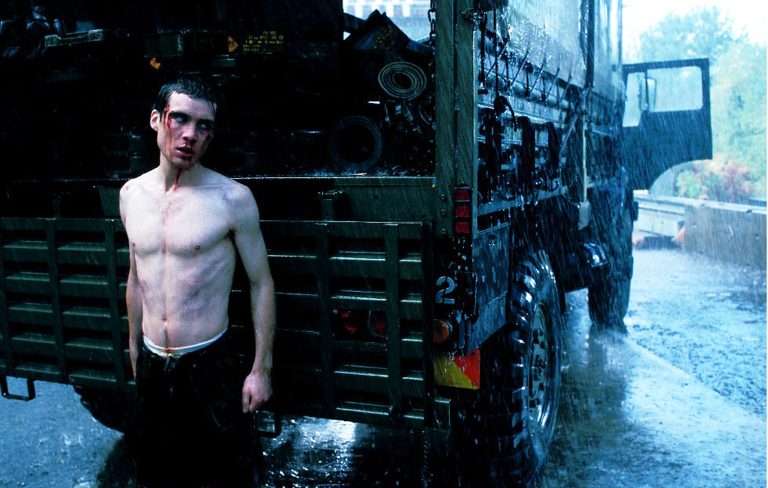

Alfonso Cuarón employs a similar aesthetic approach in his next film, “Children of Men.” The film utilizes long takes in ways that echo “Y Tu Mamá También,” but in a more intricate and multifaceted manner. The film starts in 2027 when 18 years of human infertility have left society on the verge of extinction. The social order has collapsed as the mere existence of humanity matters nothing to the people. In this world, the past becomes a vanity and the future is oblivious. In this situation, history’s materiality—what Žižek refers to as the “background” of the frame—is emphatically foregrounded in the use of the long take in “Children of Men.” This encompassing of a world view in its totality (both foreground and background in singularity) is clearly one of Alfonso Cuarón’s aesthetic motivations in both “Y Tu Mama Tambien” and “Children of Men.”

The long take reveals a material reality that is grounded in the meaning of a totalized historical experience. In “Y Tu Mama Tambien,” an innocuous long take covering a busy dialogue exchange in a car suddenly departs from the narrative foreground to depict a pictorial background: a police roadside stop victimizing a group of locals, symbolic of a wider, long-practiced, and endemic social repression of the individual.

Such political “backgrounds” are steadfastly present in the film, but it is the casualness of the hand-held gaze, in even more casual duration, which need not fixate on this brief interruption to the narrative, that is most striking as a depiction of historical experience. This approach presents the viewer with more of a personal choice as Bazin suggests. The spectators are not following the cue of the characters rather the whole three-dimensional world is presented in front of them to explore it on their own will rather than going on a guided journey according to the characters’ motivations.

But this aesthetic approach of Alfonso Cuarón becomes well-developed in his latest feature “Roma.” While both in “Y Tu Mamá También” and “Children of Men,” the camera is handheld and always on the move, the cinematography of “Roma” (done by Cuarón himself) is mostly fixed, with the use of frequent pans and tilts. Whereas the previous camerawork creates a more visceral effect by putting the perspective as close as possible, in “Roma,” the camera follows the story from a distance. While this new approach somewhat restricts the viewer from getting much closer to the image, as Bazin might argue, it gives more dimension to it. While in “Y Tu Mamá También” and “Children of Men,” the camera casually departs from the foreground and focuses on the background to emphasize the world in its totality, in “Roma,” the totality is already established.

The stark digital 65mm photography gives more depth to the images so that the foreground and background are present in a composite manner. The characters in both of the earlier mentioned films are on a journey of self-exploration and are quite apathetic about the outside world. The casual and almost sentient movement of the camera is important to unleash the larger historical context. But since “Roma” is created from the personal memories of the director, the history coexists with the personal experiences. In an interview, Cuarón stated that he didn’t want to make a movie about nostalgia; rather, he wanted to revisit the past through the lens of the present. “It is like the present’s ghost traveling to the past” (Cuarón also uses black-and-white photography). Thus, “Roma” is unthinkable to shoot in any other way.

This enhanced visual dimension creates a vast array of meanings that the audience can interpret, which Bazin argues in his third point – the ambiguity of expression. While both “Y Tu Mamá También” and “Children of Men” possess a sense of ambiguity in their images, it feels somewhat limited to a certain degree. Due to the handheld nature of the camera, the plasticity of the image is more visible, which foreshadows the ambiguity with its own meaning. Also, as the camera is always on the move, the ambiguous quality of the image is merely grabbing our attention. Additionally, the use of voiceover narration, particularly in “Y Tu Mamá También,” is another aspect of this case. The omniscient narrator knows all about the past and present of the characters, the setting, and the places they visit.

This technique creates the illusion that the film is already interpreted. But in “Roma,” the meticulous composition of the image takes us face-to-face with reality. We need to look for ourselves and extract meaning from it. Thus, in my opinion, “Roma” is the perfect film by Cuarón in a real Bazinian sense. It becomes the most mature realization of the ‘Bazinian Realism,’ as it masterfully integrates the personal with the political, the subjective with the objective, and the present with the past.

As time evolves, cinema changes. With it, the sense of ‘Bazinian Realism’ also evolves in Alfonso Cuarón’s work. From unraveling the truth from the audience’s perspective by bringing them closer to the image through long takes that maintain spatio-temporal harmony and create ambiguity of expression, Cuarón pushes the boundaries to explore cinema in its truest realist sense.