Toxic Disney Superstardom and The Lizzie McGuire Movie: This year, “The Lizzie McGuire Movie”—the theatrical star vehicle for Disney Channel star Hilary Duff—celebrated its twentieth anniversary. Through adult eyes, the film is cliched and full of plot holes, and grown-men critics used this as an excuse to trash the 2003 movie aimed at millennial preteen girls. I, a young boy on the precipice of queerness, was once obsessed with everything “Lizzie McGuire,” especially the film.

In retrospect, it’s easy to target my fixation on the fact that “Lizzie” was supposedly only made for girls, not boys. But I still delighted in watching it every time it showed up on cable well into my late teens before I shamelessly decided to purchase it on DVD. Even now, it’s a carefree romp whose seminal musical number, “What Dreams Are Made Of,” undoubtedly gave life to millions of other baby gays like me. And, as it would turn out, “The Lizzie McGuire Movie” would give rise to an entire cultural phenomenon that would span decades.

Looking back, the film is just about as poetic and meaningful as the “Spice World” and “Josie and the Pussycats” movies: all of which are campy, colorful musicals that remain endearing for those who grew up in their eras. But what remains enjoyable about “The Lizzie McGuire Movie” is what it continues to represent culturally: a turning point in both the Disney film and music industries, retroactively making it a pop cultural touchstone that is too often overlooked. Indeed, all jokes and prepubescent awkwardness aside, “The Lizzie McGuire Movie” actually represents much more than one may think and, 20 years later, is worthy of another look.

Around the time that former teenyboppers Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera were redefining notions of what it meant to behave for the millennial teenage girl, mainstream media and culture were beginning to take notice, and thus started a trend of sexualized toys and clothes for young girls which still continues to be met with controversy two decades later. Cable outlets that these girls would watch after school and on the weekends, like Disney Channel, would soon begin to take notice of such trends, too. Still, before that happened, the world was introduced to a new teen idol named Hilary Duff on the Disney teen sitcom “Lizzie McGuire,” which debuted in 2001.

Unlike the Disney television series that would follow “Lizzie” in the later half of the 2000s, such as “Hannah Montana,” “Wizards of Waverly Place,” or “Sonny with a Chance,” “Lizzie McGuire” was overwhelmingly simple and innocent. A typical episode followed Duff as Lizzie alongside her best friends, Miranda (Lalaine) and Gordo (Adam Lamberg), navigating middle school social situations while trying to avoid embarrassment and humiliation. Of course, Lizzie is a clumsy and accident-prone girl who tends to have her worst fears come true, and she has to deal with the humiliating consequences all before the last commercial break. What helped to sell and invent the series’ quirk and charm was an animated version of Lizzie, which the camera would focus on to vocalize the character’s inner voice.

Lizzie McGuire was just your average white, middle-class American preteen girl who wants to find her place in the world without having her bully and frenemy, Kate Sanders (Ashlie Brillault), embarrass her in front of the ditzy but dreamy skater boy she likes, Ethan Craft (Clayton Snyder). “Lizzie McGuire” was more influenced by the family-friendly network television sitcoms of the 1990s, such as “Blossom,” “Boy Meets World,” or “Family Matters,” than it was by any other Disney series up until that point.

And rather than imitate or cater to the mainstream primetime audience that ‘90s family sitcoms did, the series was aimed more towards kids no older than 12 turning on the TV when they got home from school, and the scripts represented that. “Blossom” might have had some jokes for the adults or addressed some challenging issues. But “Lizzie McGuire” was not where you would see characters deal with peer pressure or underage drinking, but rather the humiliation of having toilet paper stuck to your shoe in front of your crush. And just like that, “Lizzie McGuire” set the trend by catering to nobody else but the real-life audience that was the same age as its main characters.

The series aired for 65 episodes between 2001 and 2004. By then, Disney had already found another comical and screen-stealing star in the form of Raven-Symoné on “That’s So Raven,” which would become the highest-rated children’s program. But something else had started to happen behind the scenes of these Disney teen vehicles, which was the idea that if there was a market for these girls to be loveable on their own television series, there was probably a market for them to do so on their albums, too. By this point in the 2000s, artists like Spears had revitalized entirely and reinvented the market and demand for teen pop, which only made Disney’s ideas grow bigger.

Both Hilary Duff and Raven-Symoné had recorded the theme songs for their respective series, and both stars would then record songs that would appear on accompanying soundtracks for “Lizzie McGuire” and “That’s So Raven. The difference was that music or their singing abilities were not in any way a part of the premise of their programs, but more just sugar on top to make more money off the brand name. Duff began recording other songs for various Disney soundtracks. When she expressed genuine interest in pursuing a music career, Disney was the first to hop on the bandwagon: her first official studio album, “Santa Claus Lane,” was released by Walt Disney Records in 2002 and saw modest commercial success, becoming certified gold.

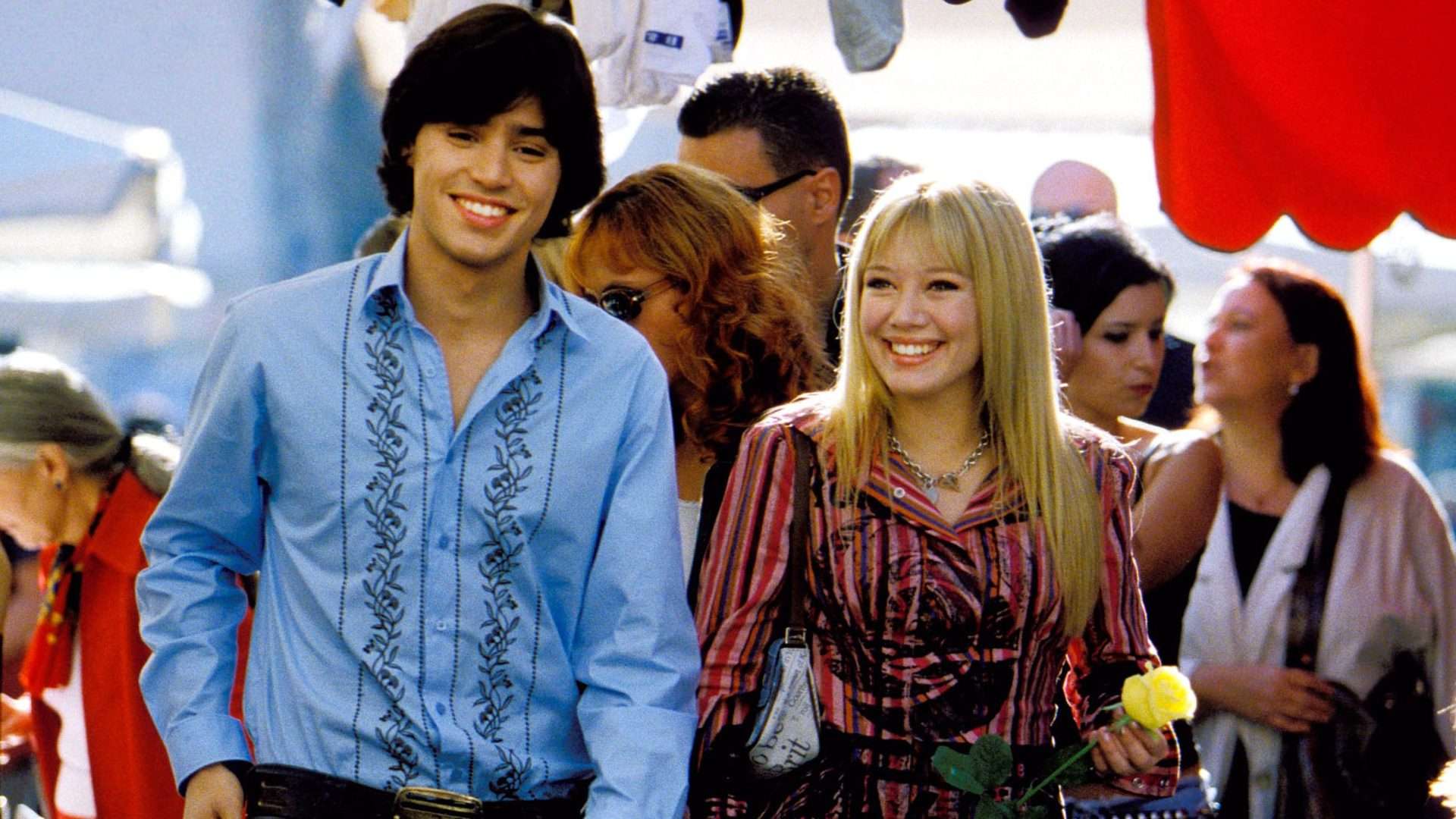

Although “The Lizzie McGuire Movie” was not the only box office hit in which Duff would appear in 2003 (“Agent Cody Banks” and “Cheaper By the Dozen,” respectively), it would undoubtedly be the most influential of all three projects. The entirety of the cast of the series reprised their roles in the theatrical release, except for Lalaine as best friend Miranda, who declined to appear in the film to focus on music—another potential teen star with a marketable opportunity. “The Lizzie McGuire Movie” follows Lizzie and Gordo’s middle school graduation (where Lizzie manages to cause the entire stage to fall down and land herself an appearance on “Good Morning America”) and their graduation trip to Rome, accompanied by the blunt yet sassy Ms. Ungermeyer (Alex Borstein).

In a twist that makes the film almost like “Under the Tuscan Sun” but for 12-year-olds, Lizzie is mistaken for an Italian pop star named Isabella with whom she bares a remarkable resemblance (also played by Duff) and is whisked away on an adventure by Isabella’s singing partner Paolo (Yani Gellman), who enlists Lizzie’s help to fill in for Isabella at the upcoming Italian Music Awards.

Faking illness and leaving Gordo to cover for her, Lizzie (who, at the beginning of the film, is shown to be an aspiring singer performing into her hairbrush) is convinced by Paolo that Isabella lip syncs and teaches her to mouth along to their song. By the time of the awards ceremony, Gordo takes the hit for Lizzie and is about to be sent home from the trip when he runs into the real Isabella at the airport, to whom he explains the entire situation.

In yet another turn of events, Isabella reveals to Lizzie moments before she is to go on stage that Paolo, in fact, lip-syncs and only wants to use Lizzie to embarrass “Isabella” in front of a crowd. In a now-iconic climax, Isabella turns off Paolo’s microphone, exposing his horrific vocal ability, and enters the stage alongside Lizzie, saying, “Sing to me, Paolo.” Isabella and Lizzie sing the first few lines of the song “What Dreams Are Made Of” before Isabella leaves her alone to have what can now be seen as a would-be iconic pop star moment and a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for young, sweet, and innocent Lizzie McGuire. That moment, and the film itself, instantly became known for all young minds who experienced it as truly what dreams are made of.

Unfortunately, “The Lizzie McGuire Movie” is depthless and leaves little to no entertainment value for grown-ups who have never heard of “Lizzie McGuire” or Hilary Duff. But for those who grew up on the series, watching the film spin-off was the equivalent of a performance high like no other. “Lizzie McGuire” was a simple and innocent sitcom aimed at middle schoolers who could easily see themselves in Lizzie’s shoes.

In the same vein, “The Lizzie McGuire Movie” was aimed towards fans of the series who could easily see themselves in Lizzie’s shoes—as a sudden pop star, suddenly “living the dream” in a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Disney’s agenda when “Lizzie McGuire” started in 2001 had shifted dramatically by the time “The Lizzie McGuire Movie” hit theatres in 2003 and solidified the message spread across most of Disney Channel in the years following: little girls should dream of being famous, and this is a realistic and healthy dream to have.

The implications and impact of the film and “What Dreams Are Made Of” became clear not even a year after the film’s release: Isabella, the Italian pop star, became a foreshadowing of who Hilary Duff was to become in real life. A mere few months later, Hollywood Records released what would be billed as Duff’s debut studio album, “Metamorphosis.” A pop rock record, the success of Avril Lavigne heavily influenced its sound, which the likes of Lindsay Lohan and Ashlee Simpson would soon copy. Duff was now living the same dream in real life that Lizzie got to live for just a few minutes before returning to her usual clumsy life. She would release a few more records with the Hollywood label after that, but none of them matched the commercial success of her 2003 release.

Duff also remained in the public conscious and pop cultural conversation as a teen idol for most of the 2000s and appeared in a string of moderately successful films, including “A Cinderella Story,” “Raise Your Voice,” and “Cheaper by the Dozen” sequel. Her public image at the time was even the subject of praise, with at least one critic commenting in 2005 that Duff did not use sex appeal to sell her albums or films like Spears or Aguilera but remained a robust role model that adolescent girls can relate to. Richard Huff from the New York Daily News called Duff the “2002 version of Annette Funicello” and observed that “Lizzie McGuire” would be both a blessing and a burden for her, saying her entire image would be tied to the character.

Duff’s transition from teen idol to adult star was also praised, although she is generally acknowledged as less “successful” than those who would come after her. By the time she would call it quits with Hollywood Records, Disney had already successfully replicated the formula they had used with her and “Lizzie McGuire” in more distinct ways, most notably with Miley Cyrus from “Hannah Montana,” Selena Gomez from “Wizards of Waverly Place,” and Demi Lovato from “Camp Rock” and “Sonny with a Chance”—all of which are either directly or indirectly influenced by Hilary Duff and what dreams appear to be made of in “The Lizzie McGuire Movie.”

The implications that Disney had perhaps failed to ponder by this point was that young children would immediately look up to any leading teen star on Disney Channel, regardless of whether anyone was genuinely cognisant of what was being fed to them. I seem to remember an extraordinary amount of time on Disney Channel circa 2009 being dedicated to presenting Selena Gomez and Demi Lovato as BFFs who were just like you but living the dream. But what dream exactly? The pressures of stardom at a young age? Growing up too fast? Life in the fast lane is hard, but it’s worth it no matter what? Cyrus, Gomez, and Lovato would also become “successful” adult stars who continue to speak on the mental health ramifications of their early years.

When Hilary Duff sang the impeccably catchy and powerful anthem “What Dreams Are Made Of” in “The Lizzie McGuire Movie,” it’s a wonder if Disney fully understood the cultural phenomenon it was about to inspire. Other media conglomerates such as Nickelodeon most notably tried their hand at the same idea with Miranda Cosgrove from “iCarly,” who at one point was the highest-paid child star on television. It’s merely late-stage capitalism at its finest, commodifying young child actresses into real estate they can market across more than one stage. A tale as old as time, perhaps, but “The Lizzie McGuire Movie” is what brought it home for the millennium.

![Last Flag Flying [2017]: Happiness, Sorrow and All That’s In Between](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Last-Flag-Flying-1600x900-c-default-768x432.jpg)