In what is perhaps the most disturbing scene in “Joker” (2019), Arthur Fleck, dressed in his clown makeup, looks in the mirror and gradually, torturously, stretches his mouth into a grotesque smile, forcing happiness onto his own face. What unsettles us is not merely the eruption of violence, but the realization that Fleck has crossed into an entirely new moral terrain. He has transcended good and evil into something more abstract, more intellectual. Something that is, heaven forbid, existential.

This is not a one-off moment in film. In the last ten years, something strange has happened to the universe of screen villains. Villains no longer merely revel in cruelty or a lust for power; they think they are philosophers in disguise. They no longer twirl moustaches; they think Camus. Their wickedness is no longer cast as pathology, but rather as a rigorously thought-out reaction to an uncontrollable world. This shift is not merely cosmetic. It is a cultural one – a society struggling with its own disillusionment, observing its villains as it cannot answer its own questions.

Thanos of the “Avengers” franchise, who slaughters half the universe not because he is driven by sadism but because he believes in what he perceives to be balance – his own metaphysical concept of justice; or the bad guy of “Animal” (2023), whose bloodied hands hide a mind fixated on betrayal, control, and corruption. They are neither driven by senseless anger like Arthur Fleck. They act because they believe in what they do, out of their own vision of life that is appallingly recognizable to the audience.

This is the trend most commonly in resonance with the philosophy of Albert Camus. In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus says: “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and that is suicide”. Camus’s absurd man is not a nihilist, but one who finds the futility of life and yet goes on living. The villains of our modern cinema live in this absurdity, not passively, but in rebellion. But their rebellion – unlike Camus’s own appeal to gentleness and decency – is in the form of violence, manipulation, and cruelty. They are Sisyphus, yes – but they’ve rolled the boulder over someone else.

Earlier movie villains were more outright. They desired money, power, or control, in association with a sense of masculinity. Hans Gruber in “Die Hard” wanted to steal from a vault. Voldemort desired immortality and servitude. Even Darth Vader, with all his pathos, was a fallen hero corrupted by power. But the philosopher-villain of the modern era is not. He is composed, articulate, and frequently deeply hurt. His words are delivered with philosophical cant – quotations regarding order, chaos, justice, and meaning.

This change comes as long-form narrative and prestige TV are on the ascendant, giving plenty of room for internal monologues and elaborate motivations. Walter White from “Breaking Bad” or Joe Goldberg from “You” justify their horrors with chilling logic. They intellectualise their crimes, presenting them as inevitable consequences of a defective world. Their reasoning, though warped, is grounded. They’re not frightening because they’re unhinged, but because their twisted reasoning almost adds up.

The look of the contemporary villain is also impressive. Consider Heath Ledger’s Joker: anarchic, intelligent, and charming in a way that skirts perilously close to being seductive. His famous line – “Why so serious?” – is not merely an insult; it’s a philosophical challenge, implying that under the façade of social order lies chaos, hypocrisy, and terror. In the same way, Anton Chigurh in “No Country for Old Men” leaves life and death to the toss of a coin, stripping morality of agency. His detachment, his unnerving calm, is frightening because it is, for all we know, a set of beliefs.

What we’re witnessing here is the convergence of ideology and aesthetics. The philosopher villain is not a plot device; he’s a mirror held up to a post-truth world trapped in doubt. In a world where old systems of meaning – religion, nationalism, even capitalism – no longer deliver, the contemporary villain steps in to fill the gap. He provides an explanation. He tells us the world is broken and why. The villain addresses our despair in language we’re familiar with hearing from late-night pondering and the dark recesses of the internet.

Also Read: Top 10 Horror Movie Villains of All Time

Social media has only helped to amplify the trend. On the internet, philosophy is distilled into bite-sized quotes, nihilism is aestheticized as dark academia moodboards, and despair is romanticized as intellectual profundity. The bad guy of today is often a hyper-online figure – half Tumblr poet, half Reddit existentialist. They are curated, stylized, and dangerously articulate. They are a product of a generation that is inured to irony, well-educated in despair, and growingly cynical about moral absolutism.

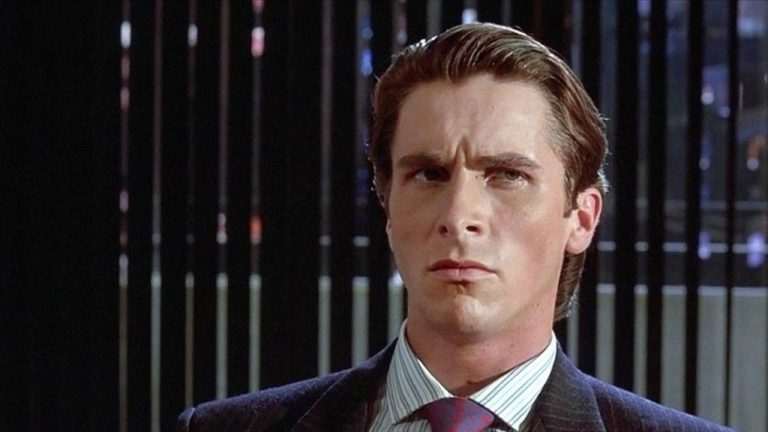

This is where the ethical dilemma steps in. When “bad” guys become intellectuals, we start sympathising with them. They express our own disillusionment so eloquently that we forget to critique their approach. Joker becomes a symbol. Walter White becomes a meme. Even Patrick Bateman, a serial killer in “American Psycho,” is now aestheticized as a misunderstood anti-hero. The distinction between critique and glorification dissolves. The Camus-quoting villain becomes aspirational.

But Camus, significantly, protested this plunge – not through naïveté, but through a profoundly radical awareness of the absurd. He did not insist on annihilation as a reaction against the pointlessness of life; he insisted on lucidity, on a determination to survive at any cost without brutality. His resistance was infused with gentleness, his rebellion rooted in the dignity of life. It was not the mindless, anarchic fury of the Joker, nor the calculating utilitarianism of Thanos. It was the rebellious intelligence of one who understood that to rebel is not to destroy, but to affirm.

This is where most contemporary villains go wrong. They take the figure of Camus’s absurd man and borrow his suffering, his isolation, his questioning of self, but omit his moral bearings. They appropriate his despair as aesthetics, but not his guilt. Their rebellion is theatrical, not existential. Violence, in their hands, is not the failure of meaning but its replacement. And yet we are attracted to them.

When we idolise them, we are betraying Camus; we make him aesthetic; we mistake cold articulation for moral seriousness. But clarity is not wisdom. A villain quoting “The Plague” as he stages mass misery is not deep – he’s delusional. And when we, as viewers, are duped by this illusion, we are complicit in the reduction of philosophical revolt to spectacle. We risk developing an empathy that is unexamined, a look that is mesmerized by coherence and blind to consequence.

Camus invited us to see Sisyphus as happy—not out of rebellion or bitterness, but out of pure awareness. His message wasn’t to set the world on fire, but to keep it in tension, and keep living. Our bad guys, if they ever read Camus, would know that revolution without compassion isn’t rebellion; it’s desperation disguised as cunning.

Where, then, do we go from here? If all the villains now sound like philosophy majors, are we doomed forever to loop into aestheticized despair? Perhaps we don’t need less intellectualized villains, but more ethically responsible storytelling – characters who break binaries without collapsing into performance.

Films like “The White Tiger” or the series “The Night Of” offer us characters whose actions are motivated not by abstract philosophy, but by structural violence, class, and caste. These villains are not Camusian rebels – they are the product of a world that averts its gaze from them until it is too late.

The villain-philosopher trope is not going away anytime soon. It’s engaging. It’s relevant. But maybe it’s time we demanded better. For complexity without enticement. For examination without romanticization, and for revolt that challenges absurdity without imposing it on others. Camus once said: “In the depth of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer”. The modern-day villain has learned the winter. Perhaps it’s time they – and we – looked a little harder for that summer too.