We often hear the saying, “Villains are not born but made”, but it’s usually applied only after a person—real or fictional—has suffered deep humiliation or moral scrutiny. Cinema, in turn, keeps reinforcing a limited idea of what an antagonist looks like. To meet audience expectations, many filmmakers in the West and the subcontinent assign stock markers to villains: unusual features, misogynistic or crude dialogue, coded skin tones, or identities meant to provoke disgust.

These devices sustain a convenient illusion, one that helps maintain social order. Plato argued that a lie that benefits the population can be as powerful as the truth. Such portrayals preserve a rigid binary worldview, where every stance demands an opposite. Anyone who doesn’t fit that frame simply disappears.

As we navigate popular culture, we should acknowledge that antagonists often perform the work of protagonists, and vice versa. They engage with society from opposing angles, yet in strong visual storytelling, it’s the antagonist who compels us to believe in their version of the world. They draw viewers in to root for them—if not immediately, then eventually. It is not appearance or stereotype that holds power in well-crafted films; it is conviction.

Skilled directors make antagonists believable even to the protagonists. In many of the best narratives, the antagonist drives the story, giving the protagonist their purpose. Over time, audiences realize that although a film or series may revolve around a central hero, what makes it memorable is the antagonist’s philosophy and politics.

Let us go through a few examples:

1. Kay Kay Menon as Brigadier Rudra Pratap Singh in Shaurya

In Indian popular cinema, antagonists have traditionally been defined by visible conspiracies. The grey areas of characters were rarely explored, and audiences resisted films in which villains overshadowed heroes. This is why commercial titles like “Zanjeer,” “Sholay,” and “Shaan” initially struggled at the box office.

By contrast, in the West, Fritz Lang was among the first to elevate the criminal mastermind, turning them into compelling anti-heroes. Their philosophy—rooted in repairing a broken society—invited viewers to consider their arguments rather than condemn them. When we witness Travis Bickle’s descent in Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver,” we’re pulled into a world shaped by alienation, moral decay, and America’s gun culture, helping us grasp what might have pushed him over the edge. Lang realized that to draw audiences into moral ambiguity, he had to present reality from the viewpoint of someone socially and ethically transgressive.

Samar Khan’s “Shaurya” presents an antagonist accused of persecuting the marginalized and violating every legal and moral boundary. Yet on screen, he appears disciplined, respectful toward the working class, and fiercely nationalistic.

As the film progresses, it becomes increasingly difficult to judge him. His presence and ideology tempt the audience to consider him righteous, even when the evidence points elsewhere. He becomes relatable the moment his personal history intersects with those who have suffered through communal violence. Viewers are caught in a dilemma: questioning him feels like questioning humanity itself, but refusing to question him makes reason and morality seem meaningless.

The protagonist, Siddhant Chaudhary (played by Rahul Bose), remains subdued—and often overshadowed—for much of the film. He becomes truly effective only when he voices the audience’s rational conscience. This raises a crucial question: what is the politics of Brigadier Rudra Pratap? Like any soldier, his mission is to protect the nation. What differentiates him from others in the film is his past experiences and how they have shaped his perception of those he believes are responsible for society’s decline. He never justifies his actions. He states his convictions firmly enough to unsettle our certainties and force us to rethink our own judgments.

2. Supriya Pathak as Dhankor in Goliyon ki Raasleela Ram-Leela

A commercial film adapted from Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” is naturally primed to appeal to audiences who embrace melodrama. Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s “Goliyon ki Raasleela Ram-Leela,” set in Rajasthan, is steeped in toxic masculinity, loud patriarchy, and pervasive chauvinism. When Bhansali frames Dhankor as the antagonist, perceptive viewers also encounter a deeper tension between female authority and male hierarchy.

Dhankor, mother of the female lead, Leela (played by Deepika Padukone), and head of a community opposed to the clan of the male protagonist, Ram (played by Ranveer Singh), wants the best for her daughter: a relationship in which Leela can carry forward female dominance in a world controlled by men. Bhansali’s depiction of Dhankor is overt and deliberately symbolic—dressed in a black saree, with charcoal-lined eyes and a serpent-shaped bindi. To truly understand her, one must read between the lines and follow Bhansali’s layered references.

Why are the women under Dhankor’s authority treated as equals to their husbands? Why does Leela dare to express love for the enemy? How does Dhankor’s daughter-in-law confidently voice her opinion before a council of men? On the surface, Dhankor’s darker traits are undeniable—she is ruthless, merciless, and deeply toxic. Yet her ferocity also stems from a sense of protection. In a patriarchal society, women often become hardened when they are forced to endure what they once resisted.

Dhankor is a survivor of child marriage and marital abuse. She refuses to let her daughter or other women suffer the same fate. It would be unfair to ignore the security she provides for the next generation. If viewed through a broader lens, the film ultimately revolves around a clash between Dhankor’s choices and the will of everyone around her.

Westeros: A Chasm Of Antagonists

We know Gotham, and it’s easy for Batman fans to relate to the city because it carries both familiarity and distance. On the one hand, Gotham feels like any city we’ve lived in or dreamt of, allowing viewers to imagine it as a place of their own. That’s the first layer of association. Dissociation begins with the name itself — Bob Kane drew it from Gothic gargoyles, giving the city a literary weight that sets it apart from modern urban identities. Another point of association lies in Gotham’s stark class divide.

The elites run the city while the impoverished either survive on the streets or spiral into chaos and crime. Ironically, Gotham’s superhero is also an elite, deepening the split into rigid social tiers. The disconnect grows when a vigilante operates outside the law to deliver criminals to the very authorities they oppose. It serves the creators’ vision, but for the audience, Batman introduces a certain emotional distance.

Also Read: The Ending and Ultimate Fate of All the Main Characters in Game of Thrones

Westeros is a fictional continent comprising seven kingdoms: the North, the Iron Islands, the Riverlands, the Vale, the Westerlands, the Stormlands, the Reach, the Crownlands, and Dorne. George R.R. Martin created this world in his seven-volume epic, “A Song of Ice and Fire,” later adapted into the series “Game of Thrones” by David Benioff and D.B. Weiss. The show opens with the Starks of the North, giving us a sense of why Northerners live where they do and what drives them. We also learn about House Baratheon and why King Robert is married to Cersei Lannister.

In Winterfell, we first meet Cersei and her brother Jaime, and the very first episode reveals their incestuous relationship. This instantly casts a shadow over Cersei, since no great house apart from the Targaryens ever condoned incest. It makes her both bold and vulnerable. But through a modern lens of urban morality, she is quickly branded immoral — as if the word were written in bold across her robe.

Cersei Lannister And Her Queen’s Breath

In popular culture, female antagonists often arrive with detailed backstories designed to justify their rise to power. Society is conditioned to expect women to surrender to social norms or accept their fate by tying it to something “holy.” Patriarchy rarely allows powerful women to exist without foregrounding a negative trait. Victims of the past are recast as conspirators or assassins, their strength revealed only through trauma. In “Kill Bill: Vol. 1 and 2,” directed by Quentin Tarantino, the Bride (Uma Thurman) becomes a ruthless avenger.

To make audiences empathize with her, Tarantino shows her family’s death as the trigger. That narrative “whitewashing” is necessary in a culture uncomfortable with women occupying traditionally male roles. Whenever a woman steps into those shoes, she’s expected to explain herself — and provide a socially acceptable reason for her transformation.

Cersei Lannister, in this context, follows a different arc, and her transformation is wrapped in quiet mystery. The audience discovers her through her words, since the series offers little insight into her childhood or adolescence. She moves through roles: the king’s wife, the king’s widow, the king’s mother, the morally corrupt woman of Westeros, and briefly, the Queen of the Seven Kingdoms. The ambiguity that the writers build around her keeps us in a constant dilemma — we hate her actions, yet we are trapped within the moral logic behind them.

Westeros has been ruled by men from the beginning. From a mad king to a drunk one, Cersei has seen every version of male power and learnt that she must operate from the shadows to secure her identity. When her husband, King Robert Baratheon, dies, Westeros is left with an adolescent heir — and Cersei recognizes her moment to take control. But why is this the perfect moment for her to turn the wheel? To answer that, we must understand her marriage to Robert — a political bargain struck between Baratheon power and Lannister wealth.

Tywin Lannister, father of Cersei and Jaime and Hand of the King, sought Baratheon support to seize control of Westeros. He offered his daughter to Robert Baratheon, sealing a political alliance through their marriage. The Baratheon dynasty is written by patriarchs, a fact made clear in the very first episode. The dysfunctional, almost hostile relationship between Cersei and Robert becomes immediately visible. Robert’s ego, fuelled by the Iron Throne, erupts when he snaps at her, “Drink and stay quiet. The King is talking.”

For a moment, Cersei exposes her loneliness, confessing, even after we lost our first boy, for quite a while, actually. Was it ever possible for us? Was there ever a time, ever a… moment? It is the first time the show allows the audience to sympathize with her before revealing her darker dimensions. Her incestuous relationship with Jaime stems from neglect and coercion, and she is fully aware of it.

After Robert’s death, when Joffrey is crowned King of the Seven Kingdoms, Cersei recognizes her opportunity: she can finally rule a man’s kingdom through her adolescent son, shaping his understanding of Westeros’ history and politics. Years of neglect and oppression have profound psychological effects. Cersei becomes the silent target of humiliation in Westeros – humiliation that remains unspoken, because acknowledging it would tarnish the values of the Iron Throne itself.

Humiliation shapes Cersei differently. It pushes her toward a single objective: to rule Westeros by any means necessary. Soft-core feminism imagines a peaceful end result, but we cannot dismiss or demonize hard-core feminism, where disorder and defiance take precedence. Women who embody this approach resist being shaped or contained by society. They seize power, intimidate men when needed, and refuse to follow expected patterns of speech or behaviour. It would be wrong to suggest they are unkind; they are simply unrestrained.

Cersei’s brand of feminism defies the norms of Westeros. She wants to preserve the dynasty, and in doing so, make sure the world understands who actually holds the reins. In one early conversation with Joffrey, she tells him, Everyone who isn’t us is our enemy (Season 1, Episode 3). In that moment, her politics becomes clear: a contradiction of anarchy and balance, power and exclusivity, resistance and demagoguery.

A flame is sustained only by wax. Without support, it dies out quickly. In the same way, Cersei becomes Joffrey’s wax. She guides his naïve, cruel mind, fully aware that he is a boy with no compass. He needs guidance – not for his rule, but for her to have her own Westeros.

While You’re Here: 10 TV Shows to Watch If You Like ‘Game of Thrones’

In a patriarchal society, a woman’s rise demands countless battles before she can wage her final war. If she constantly considers society’s expectations, she will break repeatedly, and the struggle will stall. Cersei’s strength lies in not caring about public opinion. This attitude evolves as the story progresses, but to understand her ascent, we return to her conversation with Jaime about their incestuous relationship. She says, people will whisper. They’ll make their jokes. Let them. They’re so small, I can’t even see them (Season 1, Episode 1).

Many of her decisions stem from this refusal to use society as a moral compass. Of course, very few women can hold such a stance, as it entails a certain degree of privilege. Cersei has that privilege, and she knows whispers cannot touch the choices she makes. From this, we see how every ideology requires economic support. Feminism remains soft-core and subtle when privilege is absent, but the form of feminism that embraces anarchy emerges from women with material power. Cersei’s position allows us to examine this disparity clearly.

The audience of “Game of Thrones” often places Cersei in the antagonist’s box. But if someone’s politics and way of life don’t align with ours, does that automatically make them the villain? Cersei engages with people on her own terms. She takes brutal steps not just to seize power, but to force the men around her to internalize her logic. Her actions mirror those of kings throughout Westeros, yet her gender makes them shocking. The spectacle lies not in what she does, but in who is doing it.

In the first episode of Season 2, when she confronts Petyr Baelish (Littlefinger) and reminds him that, although Joffrey wears the crown, she holds the real power, it rattles him to the core. Littlefinger’s disbelief centres on a single idea: how can a woman command the king’s guard? How can a woman outmanoeuvre a man built on deception and cunning? Cersei’s ruthless choices fit the cultural stereotype of antagonism, yet they also sharpen the image of resistance, especially a woman’s resistance. When a woman plays the same political games as powerful men, it becomes a pure expression of protest, dissent, and defiance.

In the show, Cersei never openly protests when Joffrey abuses his wife, Sansa Stark. She also doesn’t stop him from executing Ned Stark, the King in the North. This restraint comes from her larger objective: maintaining control over her son and, through him, Westeros. Yet in Season 2, Episode 9, we see flashes of her compassion when she comforts an abused Sansa in the privacy of her chambers. Here, Cersei reveals something close to her core feminine self, telling Sansa, Tears aren’t a woman’s only weapon. The line speaks volumes.

Even in the heart of power, a woman urges another to resist those who would control her freedom. At this point, the antagonist momentarily disappears. But Cersei never crosses the line into full empathy, because she understands exactly what is at stake: Westeros, a woman’s access to power, and the possibility of dismantling patriarchy from within. Instead, she leaves Sansa with a piece of open-ended wisdom which is enough to survive, but not enough to threaten her own position – a balanced approach.

A glimpse of Cersei’s possible backstory appears in a conversation between Oberyn Martell, Prince of Dorne, and Cersei. In both the books and the show, Dorne is known for its egalitarian values, regardless of gender or class. When Oberyn criticizes the mainland by saying they do not hurt little girls in Dorne — an implicit reference to the notorious treatment of women in Westeros — Cersei takes a stand. But her response is not defensive. Instead, she becomes self-critical and universal, saying, everywhere in the world, they hurt little girls. This single line reveals far more than any flashback.

It hints at the realities Cersei has witnessed or endured while growing up, and it reframes the issue as a global condition rather than a local flaw. By generalizing her comment, she quietly indicts the entire world and adds weight to the social environment around them. Her cold, matter-of-fact response catches Oberyn off guard. In that moment, he sees the depth of her insight — and realizes that breaking through her emotional armour will not be easy.

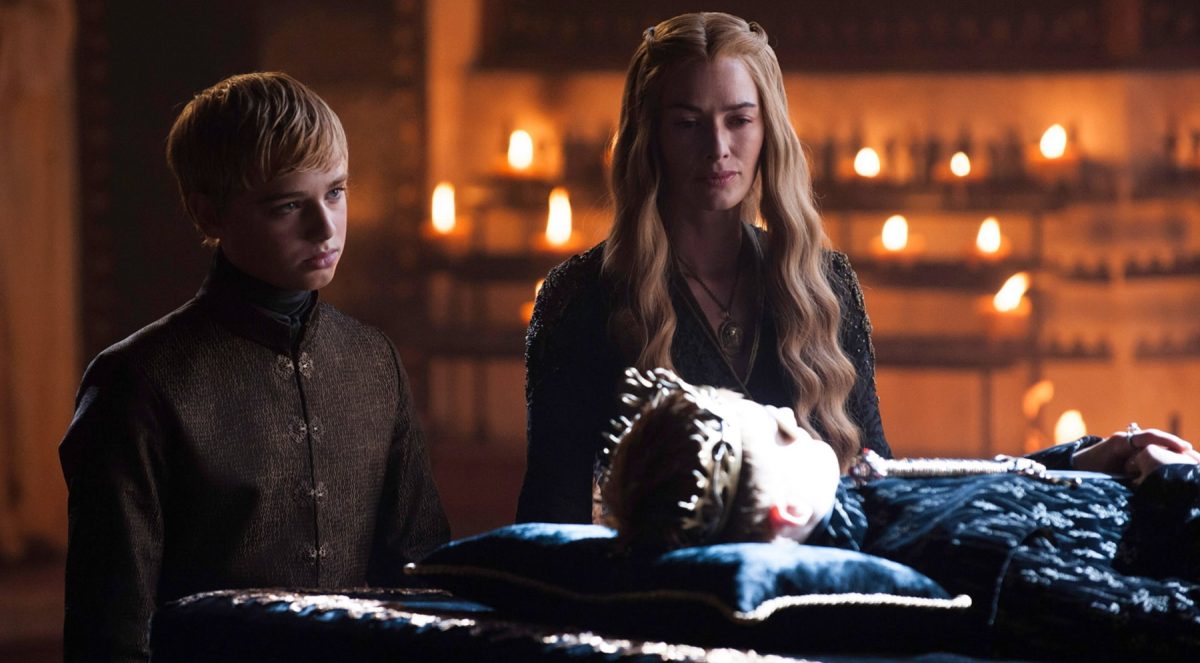

After Joffrey Baratheon’s death in Season 2, Episode 4, Tommen Baratheon is declared the heir right before Cersei’s eyes. Still a child, Tommen has no understanding of Westeros’ politics. The Tyrells step forward, and through a strategic military alliance with the Lannisters, Margaery Tyrell is chosen as Tommen’s wife. Led by Olenna Tyrell, the Tyrell dynasty arrives in the mainland, a family built on careful conspiracy.

With the aid of whisperers, Olenna introduces moral policing into King’s Landing to dismantle Cersei’s authority. Without Tywin Lannister as her shield, Cersei becomes vulnerable to a tactic often reserved for women: shame. The moral police spread rumours designed to erode her character, and they succeed.

Read: ‘King & Conqueror’ and the Long Shadow of ‘Game of Thrones’

In the Season 5 finale, Cersei is paraded naked through the streets to remind her of her weakness. But no one considers her past. So, when in Season 6, Episode 10, she utters the line, I choose violence, the remark forces everyone to confront their own conscience. It declares her intent to destroy those who brought hollow morality into the land of the Lannisters. Here again, the writers challenge the audience: Is Cersei’s brutality simply a trait of an antagonist? The moral police create a new order in Westeros — one that proves dangerous.

Cersei understands that sometimes peace requires disruption. To establish order, one must first dismantle the system that sustains injustice. Her methods are open to criticism, but seen from a wider perspective, they reveal a woman resisting public shaming, moral policing, and character assassination. The real question becomes: should women who refuse to be silenced be labelled antagonists in the modern world?

By studying Cersei Lannister, viewers begin to understand that antagonists cannot be confined to simple categories. Their personalities aren’t binary; they aren’t painted in black and white. They move through many shades, and only by examining the moments that shape their lives can we uncover their true identity, intentions, and evolution.

Cersei may be an anarchist, but she is driven by a desire to impose order on Westeros. She is conniving, yet bold enough to voice what most would consider offensive. She is not an ideal mother, queen, or ruler, but she has the determination to navigate a patriarchal world and forge her own beliefs. Cersei is a puzzle — and should we discard a puzzle simply because it resists easy solutions? Cersei is a challenge. If we refuse to engage with that challenge, aren’t we choosing the comfort of a collective defeat?

Olenna Tyrell: The Queen Maker And Broker

People raised in matriarchal societies tend to be kinder, nobler, and more patient than those shaped by patriarchy. Psychologically, women-centric communities allow greater freedom to express and accept ideas. Power rests with women, or is structured through equality and equity to balance the biological differences between people of all genders.

In “Game of Thrones,” we see a stark contrast between Oberyn Martell and the members of House Baratheon or House Lannister. In one scene, Oberyn lies naked with his partner and a sex worker — yet he treats the sex worker with genuine respect, unlike the men of other dynasties. This behaviour reflects Dorne’s matriarchal culture. A man who fails to acknowledge his feminine side often becomes intolerable. For many of us, this emotional awareness is nurtured in childhood by mothers or mother-figures. As a result, matriarchs usually struggle deeply with the idea of harming their enemies. Kindness is not easily overturned.

Olenna Tyrell embodies this conflict. She endures enormous loss before deciding that the person she wants to hurt must feel pain, shame, and sorrow. Introduced as an old woman who is witty, sharp, and relentlessly critical, Olenna projects intimidation because she must — even while living under Lannister hospitality. Her words sting. Her guidance to Margaery can seem manipulative, even cruel.

Many viewers judge her quickly. But should we label her an antagonist without understanding the source of her hatred? House Tyrell has never been defined by greed. Did they suddenly become hungry for power and wealth? A woman like Olenna, who understands female desire, allows Cersei to be paraded naked through the streets. The contradiction is striking — and contradictions always bring confusion.

Power Dynamics And Gender

Power becomes a competition when shared by people of the same gender, but it becomes a threat to the ego when two different genders occupy the same role. In daily life, we see it repeatedly: if a woman earns a higher position through her work, a man often reacts with ego rather than neutral rivalry. Yet when one man replaces another, it becomes a straightforward contest. In “Euphoria,” female characters use sensuality as a tool to gain leverage in the world of desire.

Rue (Zendaya) feels compelled to compete with Cassie and Jules (Sydney Sweeney and Hunter Schafer) regardless of class differences. Cassie doesn’t actively provoke Rue’s ego, but Rue convinces herself that to remain relevant, she must compete in every direction. A similar dynamic unfolds between Andrea and Emily in “The Devil Wears Prada.” After experiencing success, Andrea reluctantly enters a cycle of competition simply to keep up. Though each woman focuses on her own goals, both are propelled forward by the other’s achievements.

In “Game of Thrones,” villainizing Olenna Tyrell is easy — even comfortable — for audiences, largely because we are culturally conditioned to treat sharp-tongued people as antagonists. Olenna became a widow at a young age, and in her matriarchal environment, she was respected as a speaker and advisor within House Tyrell. She understood Westeros’ politics long before any other woman in the series. Patriarchal houses routinely opposed her decisions simply because of her gender.

Similar Read: 12 Epic Moments That Shaped House of the Dragon (S1)

Women with critical opinions and expertise in traditionally male domains threaten the male ego. Olenna’s battle was always against men who exposed their insecurity through bluster and dominance.

At the same time, she respected anyone who treated her decisions fairly, regardless of their source. Society taught Olenna that her weapons had to be words shaped around masculinity and power. Fighting a muscular warrior head-on would be foolish; manipulating that same warrior could benefit her house. To break into a patriarchal system, matriarchs must rely on language and use it to spark cold wars, forge diplomatic ties, negotiate marriages, and mark identity with precision.

Olenna’s conflict with Cersei is not fuelled by greed. It is driven by power and attention. Both women are labelled antagonists because their decisions defy traditional expectations of their gender. Their rivalry is fascinating to watch, but it quickly turns toxic, revealing how competition between women is rarely perceived as fair. Historically, the Tyrells were loyal to the Iron Throne under the Targaryens.

From Aegon to Aerys, House Tyrell obeyed even the most degrading royal commands. But they could not tolerate the Baratheons and Lannisters, who prioritized male dominance and treated women as vessels for childbirth. When a Baratheon seized the throne by killing the Mad King, Olenna recognized Cersei’s ambition for what it truly was. Privately, Olenna admired Cersei’s objectives. But in service of the larger strategy, she arranged an alliance through marriage between the Tyrells and Baratheons — a calculated move to sideline Cersei as competition and ultimately push the Baratheon claim out of Westeros.

The Parade Of Shame And The Contradiction

Olenna did not come to Westeros to shame Cersei. Her arrival was the final curtain. The purpose that drove her to the mainland was simple: strip the Baratheons and the Lannisters of power without harming anyone else. This becomes clear in her first conversation with Sansa Stark. Olenna invites her, and to Sansa’s young eyes, she appears to be just an old woman visiting for political alliances and her granddaughter’s wedding. But Olenna immediately recognizes Sansa as a victim of a patriarchal alliance. This is where the first curtain falls.

Lady Olenna brings clarity to an eighteen-year-old who has never been permitted to speak her truth. When Olenna says, All men are fools, if truth be told, but the ones in motley are more amusing than the ones with crowns, we understand the depth of her experience. She wants Sansa to leave Westeros, to escape its cruelty, and build an identity of her own. Olenna understands Sansa’s pain because she once lived it. She wanted to marry her sister’s fiancé but was forced into a loveless match. That history creates a striking contradiction: how can a woman who has known both oppression and pleasure fabricate information against another woman?

The answer is straightforward. Her target was never Cersei as an individual. It was the throne, the legacy of her house, and the violent politics Cersei chose to uphold. In that sense, Olenna’s objective defies her past, her philosophy, and her ideas about revenge. Lord Varys earned the title of the best whisperer in Westeros long before Olenna arrived on the mainland. He knew the value of words and used them to create chaos while strengthening the king with discreet information. Yet he had vulnerabilities, and Olenna targeted the most obvious one first: his identity as a eunuch.

The second curtain of shame falls here. Varys had manipulated Sansa into the Lannister trap, dismissed Tyrion because of his physical stature, and assisted Lord Baelish in eliminating Ned Stark. For Olenna, confronting him was a duty. He was a crucial piece in Westeros’s political machinery, and since she could not remove him entirely, she struck his weakest nerve.

It was not a noble move. But for a woman who wanted an able king on the throne and simultaneously believed a woman deserved power, weakening Varys was an act of desperation more than cruelty. In their conversation, Olenna remarks, The city is made brighter by my presence? Is that your usual line, Lord Varys? Are you here to seduce me? Oh no, please seduce away. It’s been so long, though I rather think it’s all for naught. What happens when the non-existent bumps against the decrepit? Her words make one thing clear: Olenna is not acting as an antagonist. She is extending her philosophy of dismantling those who feed on conflict and cling to the kingdom like parasites.

More Related: 15 Best Movies that Take Place Within 24 Hours

The second curtain of shame, then, is not meant to destroy — only to expose.

The universe would likely agree that throwing derogatory remarks at Tyrion Lannister should be considered a crime. He is a character who challenges norms, confronts leaders across houses, and genuinely imagines the possibility of change. Yet Olenna chooses to strike at his one true companion: knowledge.

In Episode 3, Season 5, neither Olenna nor Tyrion is prepared for the uncomfortable exchange that unfolds between them. Their meeting is brief, and because every pillar supporting the Baratheons and Lannisters must eventually fall, Olenna disarms Tyrion not through violence but by belittling the one thing that sustains him. She offers praise by negating its value, calling his knowledge useless.

When she says, I was told you were drunk, impertinent, and thoroughly debauched. You can imagine my disappointment at finding nothing but a browbeaten bookkeeper; the blow is precise. For the Tyrells, much like the Targaryens, knowledge comes through experience. Books matter, but to them, books offer only the ideas of the dead, not the tools for transformation in the present.

By insulting Tyrion, Olenna positions herself as an antagonist in the eyes of many. But it is important to recognize the larger strategy at work. Until her objective is achieved, her dream of restoring order and establishing a matriarchal balance of power remains unrealized — and unrealized dreams are merely sleepy illusions. Olenna’s cruelty here is not random; it is tactical. The insult is a strike to destabilize, not a declaration of hatred.

Standing before Tywin Lannister has never been easy for anyone except Tyrion and Cersei. Even Jaime avoided confronting him, as Tywin consistently wielded his authority as Hand of the King to keep everyone in line. Yet Olenna Tyrell’s determination did not falter when she landed a precise blow to Tywin’s ego. In Season 3, Episode 6, when Tywin approaches Olenna to propose the marriage of Cersei and Loras, she immediately recognizes that the “Emperor of Casterly Rock” has become her pawn. Tywin cannot risk an alliance between the Targaryens and the power of House Tyrell, and Olenna knows that his ambitions in the North depend on neutralizing her influence.

To puncture Tywin’s pride, Olenna simply says, Your daughter is old. I am an expert in this subject. The remark directly questions Cersei’s fertility — a wound Tywin cannot ignore. It extinguishes the arrogance of a man who turned Westeros into a landscape of violence and rigid monarchy. Does this fourth curtain of shame make Olenna an antagonist? Or does it expose a strategist who uses words to fracture tyranny from within?

After Cersei was paraded naked through the streets, a furious queen needed neither consolation nor comfort. Yet Olenna visited her in the middle of the road and said, My dear, you have been stripped of your dignity and authority, publicly shamed, and confined to the Red Keep. This fifth curtain of shame was aimed directly at Cersei, a reminder that she still wasn’t a true competitor in Olenna’s game. The tension becomes explicit in the final episode of Season 7, when Olenna confesses to Jaime about Cersei’s nature: she’s a disease. I regret my role in spreading it.

A competition between two women with the same intent and a similar psyche is never clean. Their cold war left collateral damage everywhere, but those losses were, in Olenna’s calculation, necessary to bring down House Lannister — a goal even Catelyn Stark could never achieve. To vilify a damaged woman is wrong. But given what Olenna endured — her broken dreams, her near-ruined house, and the violence inflicted by Baratheons and Lannisters — her actions become less villainous than reactionary.

Conclusion

Cersei Lannister and Olenna Tyrell are often branded as antagonists, yet reducing them to mere villains is an oversimplification. Both women emerge from systems built to silence them, and both learn to weaponize what is available: Cersei wields fear and fire; Olenna wields language, strategy, and timing. Where Cersei embraces chaos to claim power, Olenna fuels disruption to restore a sense of order. Their methods differ, but their motivations are rooted in loss, exclusion, and a refusal to submit to patriarchal limitations.

Examining these two figures side by side reveals how power operates differently through gender in “Game of Thrones.” Neither woman seeks domination for its own sake; they seek legitimacy, respect, and the right to define their own futures. Their rivalry does not come from greed but from colliding visions of what power should achieve. Cersei burns the system down to rule it. Olenna bends the system until it breaks.

In the end, both characters become symbols of resistance in a world that punishes outspoken, intelligent women. They force viewers to question who gets labelled a villain and why. Their legacy is not simply destruction, but transformation — proof that even in the most rigid kingdoms, subversive voices can rewrite the story.

![[WATCH] Video Essay Explores The Generation Gap in Two Mike Nichols’s Classics](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/the_graduate-768x377.jpg)

![Lucy in the Sky [2019]: ‘TIFF’ Review – Never Takes Off](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Lucy-in-the-Sky-768x512.jpg)