There are no such things as fixed, absolute truths, especially when it comes to the wayward progression of life. One common existential pondering to have is, as Shakespearean prose would best describe it, whether the sins of a father are to be laid upon the children. In a just world, the innocent should not be blamed nor pay for a crime they did not commit, unless they take part in it somehow. However, there’s plenty of evidence that shows consequences for an action can affect different generations to come. For instance, Gen Z must live with the aftereffects of water, air, and soil pollution caused by their ancestors, despite going to great lengths to combat contamination and reduce waste.

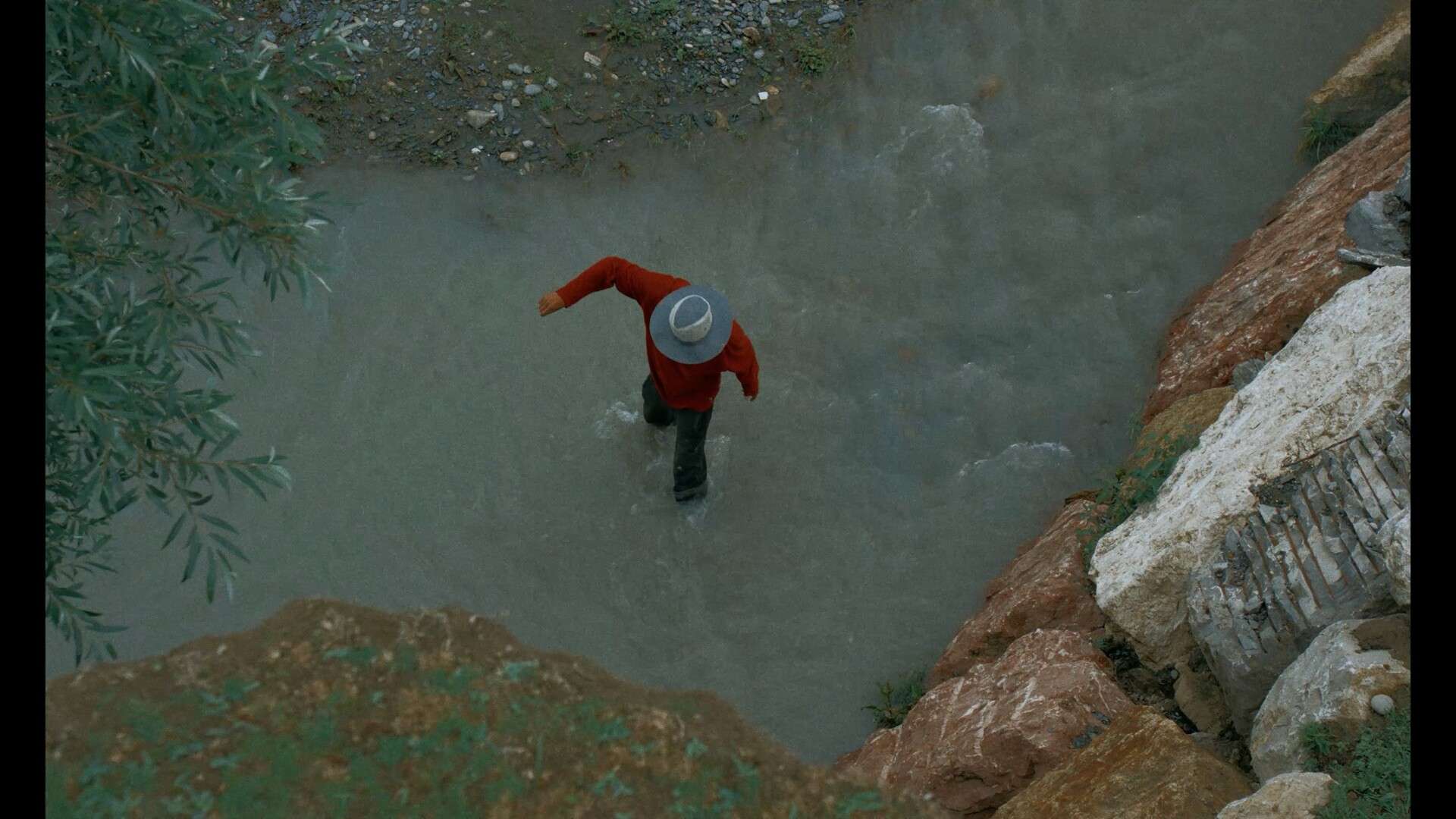

The uncertainty of absolution when it comes to generational sins is at the heart of Georgian film critic Levan Tskhovrebadze’s short film debut “Fisherman´s Burden” (2024), a crime thriller that quietly morphs into a character study. From its opening shot of two fishermen at the riverbank—father and son working together, yet standing at opposite ends of the frame, facing different directions—director Tskhovrebadze in conjunction with director of photography Theodor Gerlein demonstrates a refined eye for stunning visual composition and motivated camera movement.

As the two men go about their daily activities to earn a living, a conflict begins to unravel in the background, when a car enters the frame on the hills above—a slow pan guides our attention to it. Before we know it, a shootout between some petty criminals in a deal gone wrong takes place right in front of the countrymen. This violent confrontation results in a silver briefcase full of dirty money flowing down the river. The duo can’t resist the temptation, so they pack everything up and head for the money without carefully thinking about the consequences of robbing criminals.

This narrative framework, penned by Tskhovrebadze and Grigol Janashia, bears similarities to the Coen Brothers’ brooding neo-western “No Country For Old Men” (2007). The film, an adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s book, follows war veteran Llewelyn Moss, who stumbles upon a cartel drug-war crime scene while hunting. He takes possession of a suitcase filled with money, which sets off a chain of events. A merciless hitman, Anton Chigurh, seeks to recover the bounty, while the local sheriff, Ed Tom Bell, tries to solve the crime.

Similarly, it’s not long before the police show up looking for answers at the home of the fishermen, who have continued their routines as if nothing had happened. While their motive remains unclear, given the infamy that institutions like the police have all over the world, it is not hard to imagine that they have a not-so-honorable one, and instead just want to reclaim the prize as theirs. They are not the only ones interested in obtaining the money back, however. Soon, the criminals also come searching for what they lost, threatening to kill the fisherman’s son if he does not give them the money back.

When there is a pairing of an elder and a youngster in film, the common dynamic between the two is for the former to exhibit prudence gained through endless experience of dealing with the world and its dangers, while the latter has an inherent brashness, product of naïveté—think of the two police officers in David Fincher’s gritty crime thriller “Seven” (1995), the fading aristocrats in Luchino Visconti’s lavish period piece “The Leopard” (1963), or the hustlers in Martin Scorsese’s “The Color of Money” (1986), to name some examples. However, “Fisherman’s Burden” consciously subverts this bulletproof, though trite, formula to comment on society as a whole.

Here the recklessness comes from the father, who becomes totally blinded by greed, and ends up putting himself and his son in real danger, failing to fulfill his one mission as a parent: the well-being of his child. There is nothing more destructive of our perception of the world around us, and our understanding of good and evil, than the realization of an imperfect parental figure. That is exactly what happens to the young man over the brief course of this short film, as he comes of age, gradually losing his innocence due to the selfish actions of his father.

It is rather easy to get caught up in terrible circumstances caused by external factors. What’s hard is to flow against the shaky waters of a morally corrupt world. The personal growth posed by the unfortunate situation inadvertently propels the young man towards a crossroads where he must make meaningful choices regarding who he is as an individual. To perpetuate a cycle of violence and avarice whatever the personal and interpersonal cost may be, or to do better even when it isn’t what everyone else is doing. All of us face these types of moral conundrums on a daily basis. And it is the small actions that define who we are.

As for Tskhovrebadze, it is the small artistic choices displayed throughout that define his emerging voice as an exciting talent to watch. From the carefully layered compositions—particularly the brilliant use of a window’s reflection—to the step-printing effect followed by a freeze frame that visually captures a character’s decision-making, the film excels. The attention to detail and world-building creates a sense of life beyond the brief time we spend with the protagonists. These elements demonstrate an understanding of the importance of visual storytelling, prioritizing imagery over direct exposition through dialogue.

On the downside, noticeable amateurishness is evident during the moments of violence, all of which happen off-screen. Sure, the fatal destiny of Llewelyn Moss occurs similarly in the aforementioned film, “No Country For Old Men”, but here it comes across as less of a choice than a practical limitation. The clunky arrangement of cause-and-effect insert shots also hinders the climax from truly excelling, for they cheapen the resolution. Yet, in its final moments, the film once again delivers its message silently, without the need to verbalize the drastic evolution of the father-son dynamic at its core.

![La Soga Salvation [2022] Review: A Confusing Film, Violent for No Good Reason](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/La-Soga-Salvation-1-768x434.png)

![Cow [2022] MUBI Review : A Brutal and Brilliant Triumph from Andrea Arnold](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Cow-2022-MUBI-1-768x432.jpg)