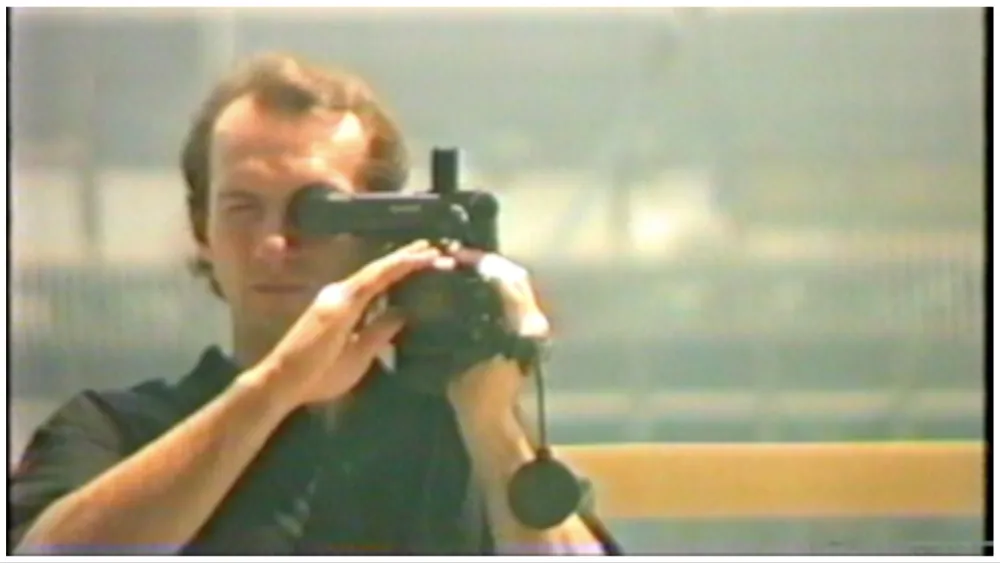

Maria Stoianova’s parents worked with the Ukrainian Ensemble Ballet on Ice. Her documentary Fragments of Ice turns to their past living in a country teetering on the precipice, amongst spaces they would rather remove themselves from. The film is essentially culled into shape from a series of VHS tapes shot on a camcorder by her father between 1986 and 1994. As soon as he gets the camera from someone in the troupe, he grows besotted with it, placing almost everything and everyone under its gaze.

The graininess of the footage evokes the intimacy with which her father regarded his camera, using it not just to record the minutiae of family life and inscribe it into memory but also to articulate his own desire for what life outside the stranglehold of the USSR can carry. While the scope seems condensed, it invites a broader, discursive reflection on an entire generation’s yearning that may come up against a reality harsher than its rose-tinted assumptions.

A telling detail emerges when her father confesses his career in figure skating might have been impelled by his foremost dream of traveling out and abroad, which stood a chance if he pursued it. Therefore, the foreign tours that he is able to do with his ballet troupe hold a definitive place. Its frequent, glowing mention supersedes everything in his life. The ambit of his aspiration is determined by this insistent pull. The film abundantly stresses this inclination of his, as he seems to emotionally check out of existence in a rapidly disintegrating homeland. At one point, the director states how he never felt proud of representing the USSR and instead felt more comfortable when dissociated from it.

There is expansive wonder and awe with which the footage garnered on these foreign trips is imbued. The lure of capitalist economies in their surging consumerist pull is hard for him to shake off. He is fascinated with the ‘extraterrestrial wealth of the West’; it has all the flash of an intoxicating, radically new world to him that abides by a set of lifestyle choices drastically different from those available in Soviet Ukraine. Despite their despair over their country slipping into worsening chaos and skyrocketing inflation, the parents remain cynical about the possibility of the Soviet collapse and Ukraine’s independence.

With sinuous subtlety and lightly rendered suggestive strokes, Stoianova makes a gripping, complex case for the clobbering love-hate duality that permanently haunts them, as well as the lingering threat of displacement. In spite of a willingness to distance himself from the binds of the Soviet Union, the eventual decisive transition, his move out of the ensemble into individual gigs elsewhere in the UK aren’t easy shifts. Stoianova sensitively peers into these points of inner tussle, letting us glimpse the momentousness of every choice her parents are led into making as a byproduct of their larger tense socio-political circumstances. Their apartment in Ukraine is almost falling apart.

The director’s voiceover is a constant, scrupulous guide in helping us parse this chronicle. For any director, the decision to rely so extensively on the voiceover is certainly a loaded one, and I’m certain Stoianova mulled this over at great length. While it indubitably helps in stitching some of the disparately sprawling memories over the years, occasionally, it goes too nigglingly far in re-establishing or driving forth a point of which the viewer has already got a drift. Of course, Stoinavo’s adult voice is filtering through stuff that she witnessed and observed as a kid, applying her present, experientially richer understanding and retrieving shards of the past.

It is always a tricky balance between straddling images and a punctuating voiceover. Whenever the latter tries to bear itself down too heavily on the patchwork of particular videos circling intimate family moments, the film’s grip on its otherwise compelling characters turns a tad wobbly. It is almost like the director gets too caught up in presaging and tracing an outline of what we should or might be feeling. There are also these superfluously wordy bits scattered throughout when certain recounted memories come off as too burdened by the director’s present-tense insights. Reams drawn from the Ballet’s archive with dry, droning stress on adhering to the official code of elevating ideological and educational standards also intersperse the voiceover, a choice that doesn’t reap much dividends beyond the necessary degree.

Nevertheless, Stoianova maintains a terrific, confident hold over the narrative trajectory that she wishes to take us through. Very quickly, she manages to make us invest and care. The emotional thread stays intact throughout. While her mother somewhat gets the short shrift, her father’s presence and individuality register powerfully and often with a hint of wistfulness. On one of his first international trips, he is so hauled up in shopping he holds up his entire group during the time of departure. Whenever he is able to temporarily get out of the USSR for any work reason, he says that is when he feels he can breathe. To be out of the KGB’s glare is in itself a massive, albeit fleeting relief.

Through the vignette-like structure, Fragments of Ice spans a fraught political history by firmly locating a deeply personal example. Sticking to an authorial voice that’s never whiny nor mawkish, the film is focused on its strain of hardened, clear-eyed retrospective realism. With an immediate directness, Stoianova compels us to reckon with a complicated legacy that is important to untangle for the sake of understanding our own selves poised at various steps into the future.

![A Gaza Weekend [2022] ‘TIFF’ review: A Massively Entertaining Tale of a Couple Helplessly Searching for Safety](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Gaza-Weekend-2022-768x384.jpg)