What makes Gaspar Noé’s cinema so incredibly striking is because of an unlikely philosophical conviction: destruction. There’s a recklessness in Noe’s cinema that’s motivated and idiosyncratic. A sense of organized chaos underpins his art. It’s not just his unwillingness to conform and obey conventions that showcases his inimitable style, but his ability to reconstruct a language on the principles of aesthetics. Gasper Noe deconstructs style over substance to the point where the style can confidently supplant the need for substance; his films are spiritual, sensual, and scintillating to watch – the execution on a bare-boned plot you can summarize in a paragraph or two.

The Argentine-Italian auteur of French cinema has never shown the hardcore dispositions of a director or, at the very least, strictly adhered to the guidelines of making a good film, fine-tuning plotlines or building character arcs – crafting a comfortable, immersive experience is not what defines his oeuvre. It’s the brilliant subversion of tradition that makes his films memorable while still retaining and improving the finer elements of filmmaking to create a wholly cinematic rollercoaster. Destruction is a form of art in and of itself, and the poster boy of the New French Wave does it very well.

Despite the controversial themes, gratuitous violence, and emotionally exhausting nihilism, Noe doesn’t do things for shock value – he takes a sledgehammer to our cinematically ingrained ideas of life, death, and everything in between. Love isn’t just letters, roses, and romantic gestures; it’s also the compulsion to take care of someone through sickness. Sex isn’t a pornographic build-up to pleasure; it’s messy, confusing, and painful, and it can become a self-destructive coping mechanism. Life isn’t a linear dimension; death isn’t the end of things, and art doesn’t have to be comprehensible to be labeled as such.

Each of his films is a philosophical and political undertaking, exploring themes of masculinity, spirituality, sexuality, and love through his fearless probings into the complex machine that is the human body. His films explore the flesh and sinew of emotions. They operate like cinematic autopsies of abstractions. Bloodied frames are red-hot and blinding, sweltering oranges, unnerving greens, and crushed darkness color the appropriately twisted underbelly of France. In fact, Noe’s depiction of suffering is rooted in passion; from its perversion emerges an aesthetic that’s hard to take your eyes off from. The depths of depravity are examined with attention to detail and flair.

It’s easier to hate a Gaspar Noé film than it is to love them, but like a toxic relationship, you give it way too many second chances. It’s edgy to the point of parody, fractured to a point where narratives muddle and plot lines become reductive. But there’s an unshakeable aura in its existence. The reason his films are exasperatingly beautiful is also a reflection of his ultimate statement: on the uncomfortable truths of our bodies and the consequences of inhabiting one, our animalistic and suppressed proclivities towards destruction and danger, the soft comforts of humanity tainted by death and suffering, the horror in beauty and its converse; that life is just a major trip before the ultimate embrace of death. Being human is a gnarly business.

So, pop a pill, or don’t, in fact, do not be under the substance of anything while watching a Gaspar Noé film; it’ll just make it worse. Here is a ranking of the maestro’s films.

7. Lux Aeterna (2019)

“Lux Aeterna” is a filler film in Gaspar Noé’s filmography for two reasons: 1) it’s 51 minutes long, and 2) it’s borderline unwatchable. Not that it’s a terrible film, just that the last 20 minutes is an epileptic’s nightmare come true. Noe deliberately uses a red-green-blue strobe effect in the film’s last act, and it’s enough to scramble your brain clean. “Lux Aeterna” (‘eternal light’ in Latin) is Noe at his most experimental, completely abandoning narrative conventions to create a sensory, audio-visual assault on the senses. A parody mockumentary about a shoot gone awry, the film is an attempted exercise on a thesis conveyed to us in the first frame: a quote by Fyodor Doestovesky about the ultimate happiness being in the few minutes before an epileptic seizure.

Gasper Noe works to it by employing a thin storyline while still employing (effectively) some innovative visual tricks like split-screen cinematography and fluid switches between objective and subjective shots. The film starts as a series of conversations between the director Beatrice Dalle and actress Charlotte Gainsbourg (playing themselves) on the set of their witch film, and the scene to shoot features witches burning at the stake. What begins as a sharing of stories snowballs into a production nightmare and technical glitches. Annoying cast members start plaguing the shoot, stranding its writer and director and destroying their vision. Noe maintains a steady level of chaos throughout the 51-minute run-time. But his audaciousness gets the best of him; the end product is a headache-inducing meta-film that’s neither entertaining in its commentary nor redeeming in its visuals. All you’re left with is a temporary white scar in your vision.

6. Love (2015)

Gaspar Noé’s art erotica “Love” creates its artistic merit through its frank depictions of sexuality and relationships. The film centers on the life of Murphy, an American studying film in Paris. He meets the beautiful Electra and enters into an emotionally turbulent relationship. Things start getting interesting when their young neighbor Omi joins in for an unlikely partnership. The plot is simple, a little contrived, albeit Noe doesn’t care about narratives greatly; plots are used for his stylistic imposition. It’s a striking film—the cinematography by Benoit Debie morphs and changes with the mood of the scene. The brilliant use of silhouettes, negative space, and static camera placements, paired with the fluid tone reveling in primary colors, humanize (and demonize) Paris with allure.

In this film, Coitus is as honest as it can get. Noe wishes to make the statement that sex is not perverse or taboo. The parties, the quick hookups, and the incredible menage-a-trois scene (the narrative high point) are done artfully. Noe’s vision of making a love story through sex is apparent but not well-executed. The sex scenes are the centerpiece of the film. So, naturally, each scene feels like a long, winding buildup towards it. The 2-and-a-half-hour runtime tires you because the characters are pretentious assholes who philosophize their drug-induced sexcapades.

Is a scene of a penis ejaculating towards the camera (in 3D for some viewers!) really that necessary? The discourse around sex in cinema and pornography is compelling. But Love’s sex scenes are to prove a point and not to provide commentary, making its existence a watery argument against censorship. It’s a beautiful film in many ways, but it always comes back to its unfortunate label: a sad art porno that, as Noe himself put it, “gives guys a hard-on and makes girls cry.”

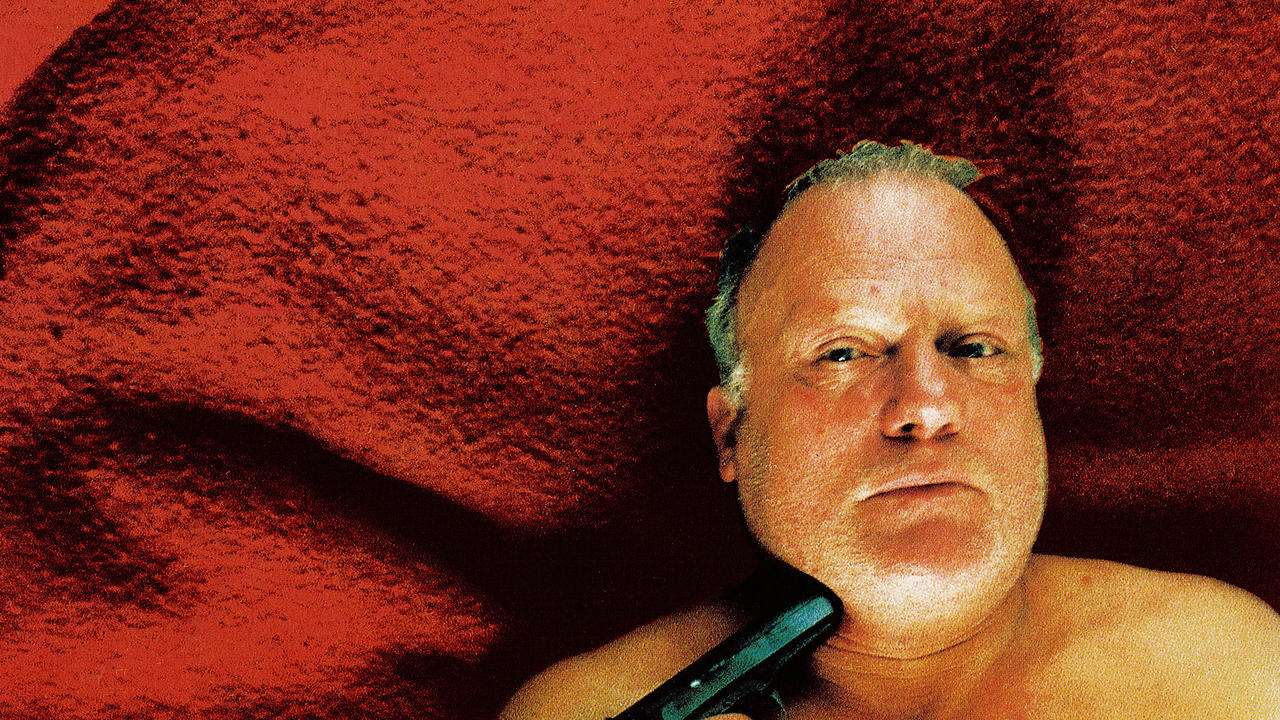

5. I Stand Alone (1998)

The spiritual offspring of Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver,” openly cherished and referred to by Noe. But “I Stand Alone” is immersed in a grime and filth that’s unlike anything you’ve ever seen. The film is a sequel to Noe’s short film, continuing the same characters and exploring the same perverted universe. We see France through the piss-tinted eyes of The Butcher, played by a formidable Phillipe Nahon, a heavy-set anti-social personality devoid of humanity. In fact, the narrative is a series of ramblings stitched together. The Butcher is a vile, disgusting monster who’s come out of jail after killing an innocent man who he believed raped his daughter.

He’s back in society to start afresh, but the France of his time is a depraved hellhole, and The Butcher’s thoughts reflect exactly that. Noe’s depiction of misery and squalor is deeply unnerving because the violence is ever present from the start, and it’s eerily subtle. Noe’s direction is formal here; the experimentation is minimal, seen more through the narrative than the technical side. It’s fascinating to see how Noe builds on these themes with flair and detail because “I Stand Alone” is unabashedly a Gaspar Noé film, but it feels oddly held back. The climax is extremely upsetting, but it’s a searing portrayal of sexual and emotional repression. Quite the indie darling, go into this blind and come out of it feeling like you need a shower.

4. Enter The Void (2009)

“Enter The Void” arguably has the greatest opening credits in cinema – a fast-paced succession of text in trippy art styles, edited to a bumping techno track that perfectly sets the tone for Noe’s massive philosophical endeavor. Clocking at a monumental two and a half hours, “Enter The Void” is a neon-colored endoscopy into the soul, probing the immortal, the unyielding, the terrifying, and the ever-beautiful facets of the human condition. Drug dealer Oscar and his sex worker sister Linda are living in the underbelly of Tokyo, a universe of nightclubs and hotels. Oscar gets killed in a drug deal gone wrong, and the film follows his soul -literally – going through dreams and realities, changing between a third-person and a POV perspective.

Oscar’s journey sees him seeking redemption and answers in Noe’s version of the afterlife, The Void, a discordant symphony of sound and imagery, surveying the consequences of his death and his past. Noe’s imagination of the afterlife is striking, sensual, and audacious, which is also mature and sometimes rooted in reality. As Noe put it, “Enter The Void” is a ‘psychedelic melodrama’ and a moving one at that. From the neon-drenched love hotels of Tokyo to the muted and soft memories of Oscar’s past, Noe doesn’t just give us an imaginative rethinking of the afterlife but a powerful story of family, grief, rebirth, and reincarnation. It’s a magnificent work of audio-visual extravagance, cementing Noe’s reputation as a brilliant technical filmmaker.

3. Irreversible (2002)

“Take the underpass, it’s safer,” says a pedestrian to Alex, who’s going back home from a party. In retrospect, after subjecting yourself to this nightmare replete with audio-visual trickery, extreme gore, and sexual violence, there’s something bone-chilling to know that none of this could’ve happened if she hadn’t listened to the stranger. Perhaps the thesis of “Irreversible” lies in how our fate is set in stone. And winding back the clock does nothing but draw out the helplessness in realizing it is unchangeable. Time is the villain in “Irreversible.” The film pushed Gaspar Noé into the limelight and made him the face of the New French Extremity Wave. Mass walkouts from its premiere at Cannes, with some being physically sick, cast a spell on its mythic reputation that morphed into the infamous label of being one of the most violent films of all time.

A rape-revenge thriller uncompromisingly and stylishly shot, it stars French tabloid darlings Vincent Cassel and Monica Belluci, the former playing a boyfriend exacting revenge on the man who raped his girlfriend. The destruction unfolds over one night, encapsulating the urgency, and Noe, in his infinite (and problematic) wisdom, frames the narrative in reverse. It’s a disorienting but engaging ride. The camera is ever-rotating and fluid, swooping and uncut, essaying destruction and despair with unflinching honesty, accompanied by a nauseating score.

Noe bookends the nihilistic odyssey with an unlikely dictum flashing loudly: LE TEMPS DETRUIT TOUT (time destroys everything). The uncomplicated framing enables a philosophical viewing, albeit it is held back by the problematic depictions of marginalized communities and the rape scene itself. “Irreversible” is a temporal horror movie exploring the bowels of human nature and its universal sentimentality, with equal exuberance, tainted and ruined by the corroder of marble and gilded monuments: time.

2. Climax (2018)

The promotional material is as edgy as Gaspar’s films. “You despised I Stand Alone, hated Irréversible, execrated Enter the Void, cursed Love, come celebrate Climax.” Noe emerged from his three-year hiatus with no plot and a dream (similar to his previous film, the critically-panned “Love”). Noe went into guerilla mode for the film’s production. He didn’t have a script but an outline with a beginning and end. He cast dancers with no acting experience. There were no rehearsals, line reads, or pre-prepared dialogue, so every scene was improvised. But Noe’s demonic style offsets these filmmaking taints by tapping into a vein of pure artistic rage. What gushes is an acid trip to Hell.

“Climax” is what you get if a “Step Up” film was directed by the Devil. It’s 100 minutes of a lucid nightmare – chaotic, violent, absurd, horribly twisted, surprisingly entertaining, and quite senseless because it operates on a dreamy logic devoid of rational treatment. Loosely based on a real-life incident, “Climax” is a liberating but formal testament to Noe’s ability as a technical storyteller – the visuals commandeer the story, like a dance floor, it gives a confine for the story to breathe and contort in. The nearly 10-minute-long one-shot opening dance sequence, the credits smack dab in the middle of the film, and the red-drenched final act with the camera going all topsy-turvy sums up to create a nauseating, anxiety-inducing odyssey into the stoner’s mind.

The story is simple: someone spiked the sangria with LSD at a dance troupe’s rehearsal with LSD, and they’re all tripping balls. But “Climax” subverts genre conventions by confining the perspective outside of the trip, detached from the subjectivity of the character’s minds, examining the consequences and effects as a helpless viewer. The dancers lament, scream, and freak out, yet we never see the subject of their horror; instead, we see their jarring physical reactions. And it is utterly brilliant.

1. Vortex (2021)

“I showed the film to my father a few months ago, and he said he thinks this is my most violent movie ever,” said Gaspar Noé in an interview with Letterboxd. The irony of this statement lies in how his most violent work is the very one that lacks or, to a great extent, subverts his trademark style. Gaspar Noé came up with the idea for “Vortex” after he suffered a brain hemorrhage in early 2020. With a renewed appreciation towards life, Noe pours his gratitude into a film that encompasses the essential truths of life – aging, death, and suffering – with luminous vulnerability.

“Vortex” is a bracingly honest plunge into despair. Noe translates a profoundly personal story unwavering in its emotion that never teeters into incoherent cinematic showmanship despite the film’s screenplay being ten pages long. In fact, he achieves a perfect equilibrium of style and substance; the visuals never become gimmicky and redundant, instead strongly reinforcing the themes of this tragic tale of a couple forced to drift apart by forces they can’t control. An old French couple live a peaceful existence in their home, choked with books and adorned with movie posters. The husband is a writer and retired psychiatrist who lives with his wife. Their lives are threatened by their ailments; the husband has a heart condition while the wife suffers from dementia, the latter of which derails their relationship, sending each other into confused solitudes as indicated by a split-screen.

“Vortex” put me in an emotional fugue state similar to that of Michael Haneke’s “Amour,” a film that shares the same plot. While Haneke is more philosophical and rigorously inclined in his approach, Noe’s vision has a subjective tint and allows horror to seep in. It’s a visually depressing film; sadness simmers at a steady pace, gloom and terror hang like a shadow, the frames feel claustrophobic and suffocating, and the helplessness is what gets to you. Noe’s technical exuberance is stripped down, being the dominant cog in the narrative, elevating the seemingly simple story into his most accessible film. Its approach is intimate yet unnerving; a heavy strain of unpredictability wrings tension and fear.

The wife starts forgetting her pills; the husband loses her in the street; the son asks them for money for drugs. The tragedies keep piling up for a gut punch of an ending. You are forced to watch two people wither away. It’s death in slow motion, 24 frames per second – the quiet death of sanity, love, and the very company that’s kept two people together for so long. “Life is but a dream. A dream within a dream,” remarks the husband at the start of the film, unaware of the coming nightmare. “Vortex” will make you come to terms with your feeble mortality, of your weak body and perishing brain, because everyone will succumb to the swirling darkness of death. But even still, the soul will live on. At least, that’s what Gaspar believes in.

Read More: The 10 Most Unsettling Movies You’ll Ever See