In a lot of ways, silent cinema was an accomplished art. While the German expressionist school of film-making in the 1920s enhanced the content of the image through lighting and sets, the Soviet silent cinema applied its arsenal of editing techniques to singualrly depict an event or emotion on-screen. Sound, if it was added to these works, could have only played a minor, complementary role. Naturally, when we think of Soviet editing revolution and its rigorous aesthetic, we would also recall the rousing display of nationalistic fervor and solemnization of the alleged Soviet values. To put it another way, the revered film-makers of early Soviet cinema didn’t possess a great sense of humor. But the Soviets did make comedies and traditional melodramas, which were just not widely available until few years back (and most of it still remain lost). Soviet silent comedy, in particular, was partly inspired by the American slapstick comedies of the era and yet it also retained much of Soviet cinema’s unique artistry or peculiarities.

Of course, it served laughs as well as the Party propaganda. A well-researched article on Soviet silent cinema posits, “Analysis of Soviet film must forever dance between admiration of the finest examples of its artistry, and recognition that much of that artistry was in service of communist propaganda–often willingly” [1]. While Soviet avant-garde and montage theory was often associated with filmmakers like Sergei Eisenstein & Dziga Vertov, these elements were also used in Soviet silent comedy to create an interesting effect. Such films didn’t have many laugh-out-loud moments. It would rather astound you with its formal innovation while evoking series of quiet chuckles. Still, the most commercially successful silent comedy at that time in Soviet Union borrowed elements from the works of Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd. Obviously, the majority of silent comedy listed below belongs to the former than the later.

After the 1917 Russian Revolution, private studios continued making films in Russia. Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks gradually took steps to turn cinema into a state industry. One year after the end of First World War, in 1919, agitprop (agitation and propaganda) trains, with theatres and cinema in the carriages, departed from Moscow to travel across Soviet Union [2]. The aim was to promote Leninist reforms. In 1921, famine affected the Volga and Ural regions, killing approximately five million people. In the same year, Lenin proposed the New Economic Policy which temporarily retreated from the Party’s extreme centralization and even gave consent to the return of markets.

Similar to 10 Best Soviet Silent Comedy Films: 10 Essential Japanese Silent Films

The marriage between propaganda films and new film forms happened in the year 1924, spearheaded by Lev Kuleshov, film theorist and filmmaker. Some of his notable students were Vsevolod Pudovkin, Boris Barnet, and Vladimir Fogel (the star silent comedian). Sergei Eisenstein joined this film movement by starting his career in theatre, aspiring to create an aesthetic to represent the working-class. 1924 was also the year Lenin died. In the subsequent years, the Soviet film-makers made bold, cutting-edge silent cinema, but often under government supervision. As Soviet silent cinema reached its zenith of expressive power, NEP was abandoned due to complex political conflicts. Stalin triumphed over his political rivals, and by the mid-1930s he unleashed the Great Terror.

Soviet silent comedy of the 1920s, however, brimmed with utopian aspirations and romanticism. The communist idea of Soviet Union was still fresh and strong, before it got lost in the purges, economic disaster, and lies. And despite working within in a rigid belief system, early Soviet filmmakers manufactured new forms of expression and artistry which still remains fascinating. No one hammered in the political points as artistically as the Soviets, especially compared with the gimmicky nature of the Hollywood propaganda machine.

Listed below are some of the films you can get yourself acquainted with (all of it available on YouTube) before moving on to the works of Soviet intellectual heavyweights. Or if you are already familiar with the dialectical applications of Eisenstein, why not watch these Soviet silent comedies which possess a great deal of chutzpah unlike any other silent comedy. Boris Barnet’s 4-hour adventure-comedy Miss Mend (1926) is missing from the list due to the lack of English captions. Protazanov’s satirical account of religious duplicity, St. Jorgen’s Day (1930) is not in the list because it’s a partly dubbed film. If I have missed discovering any other worthwhile Soviet silent comedy not mentioned in the list, please educate me in the comment section. Happy reading!

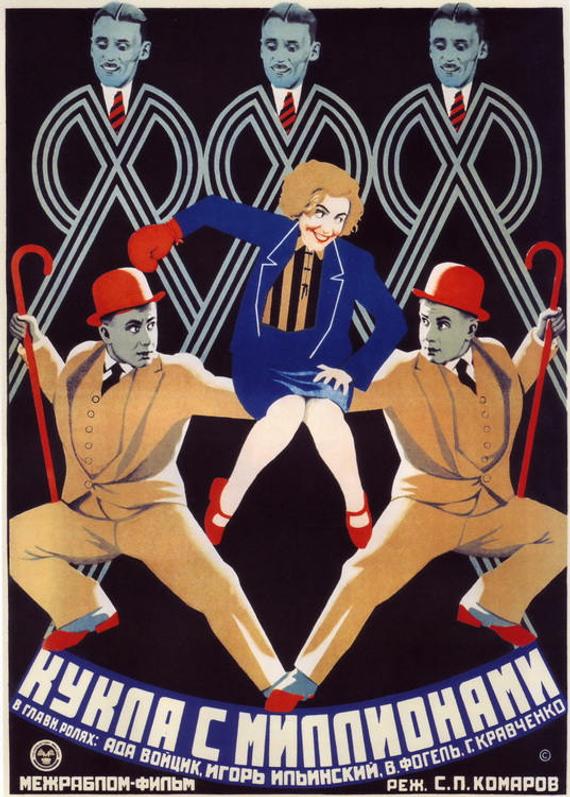

10. The Doll with Millions (1928)

The Doll with Millions was one of the two films directed by Soviet actor Sergey Komarov. His directorial debut was A Kiss from Mary Pickford (1927) which interestingly stitched up the documentary footage of Hollywood superstars Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford’s visit to Russia into the narrative [3]. That makes it an intriguing footnote in Russian silent cinema history, but on the whole A Kiss from Mary Pickford is a bit tedious. The Doll with Millions has more of the classic silent comedy feel: a tale of impossible pursuit made for the sake of millions.

Related to 10 Best Soviet Silent Comedy Films: Our Hospitality [1923] Review – Evoking Poetic Rhythm & Artistry within Slap-Stick Tradition

The Doll with Millions opens in Paris with a rich old widow in her deathbed. Her good-for-naught nephews, Pierre and Paul are the possible inheritors. But they are in for a shock when their aunt leaves the entire fortune to her lost niece Maria Ivanova. The clues left to find Maria are that: she is a 17 year old girl with a birthmark on her right shoulder living in Moscow; and the documents proving Maria’s identity is, unbeknownst to her, is hidden in a doll. Pierre and Paul race to Moscow to find the doll, the girl and marry her. Maria Ivanova is the perfect, resourceful proletariat student who when learns about the millions is happy to use it for improving the students’ living conditions. Of course, how could the greedy Parisians know that?

In The Doll with Millions, the familiar tropes of silent comedy – slapstick, fast-paced chases, false identities – are utilized to create some funny situations. The topical concerns of Soviet society and political context are sprinkled here and there. Overall, it’s a accessible, harmless Soviet silent comedy that owes a lot to its American counterparts.

Watch The Doll with Millions on YouTube

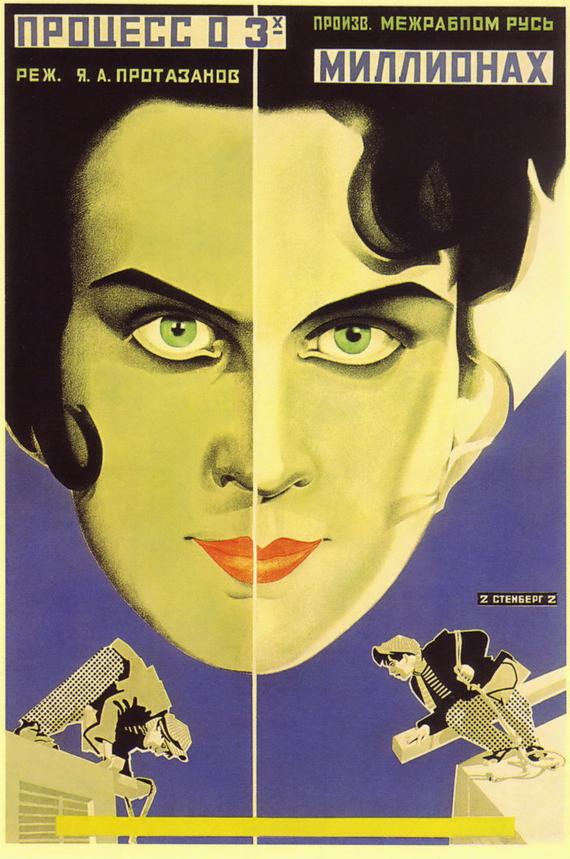

9. The Case of the Three Million (1926)

Yakov Protazanov could be called the Tsar of Russian silent cinema. He made his directorial debut in 1911. His 1913 film The Keys to Happiness was the most expensive film made at the time which also set box-office records. But after the Revolution, between the years 1920 and 1923, Protazanov lived in Berlin and Paris. Eventually, he was persuaded to return home. His first Soviet film was the preeminent sci-fi adventure Aelita (1924). The subsequent Protazanov’s Soviet movies were not really the ‘revolutionary’ works like that of Sergei Eisenstein, Vselovod Pudovkin or Alexander Dovzhenko. However, his films were widely distributed and earned huge profits.

Apart from commercial success, Protazanov didn’t much get caught in the artistic or political disputes that was plaguing the rookie Soviet directors of the time. Protazanov’s choices of projects were also unpredictable. He made comedies after Aelita , unlike his more serious pre-Revolutionary cinema (‘The Queen of Spades’, ‘Father Sergius’). He did toe the Party line in his narratives, lionizing the proletariat and gleefully reprimanding the bourgeois. Yet these were also simple, enjoyable adventures with typically Soviet characters. The Case of the Three Million was preceded by The Tailor from Torzhok, a comedy about state lottery loans which was more artfully dealt with in Boris Barnet’s The Girl with the Hat Box.

Related to 10 Best Soviet Silent Comedy: Safety Last! [1923] – An Incredibly Exciting Slapstick Spectacle

The Case of Three Million was an adaptation of Umberto Notari’s play The Three Thieves. It isn’t comprised of any propaganda related to any State schemes. Nevertheless, Protazanov’s mockery is directed towards the classy types of society. In this silent comedy, Protazanov quickly introduces three thieves from three different parts of society. One is a impoverished petty thief, the second a conman operating in the higher echelons of the society, and the third a banker involved in a shady scheme with obese, avaricious priests. The smalltime thief and the ‘international’ thief learn about the three million in the banker’s possession. What unfolds is not a meticulous heist but a mildly funny commentary on the societal double standards and dishonesty.

Stream The Case of the Three Million on YouTube

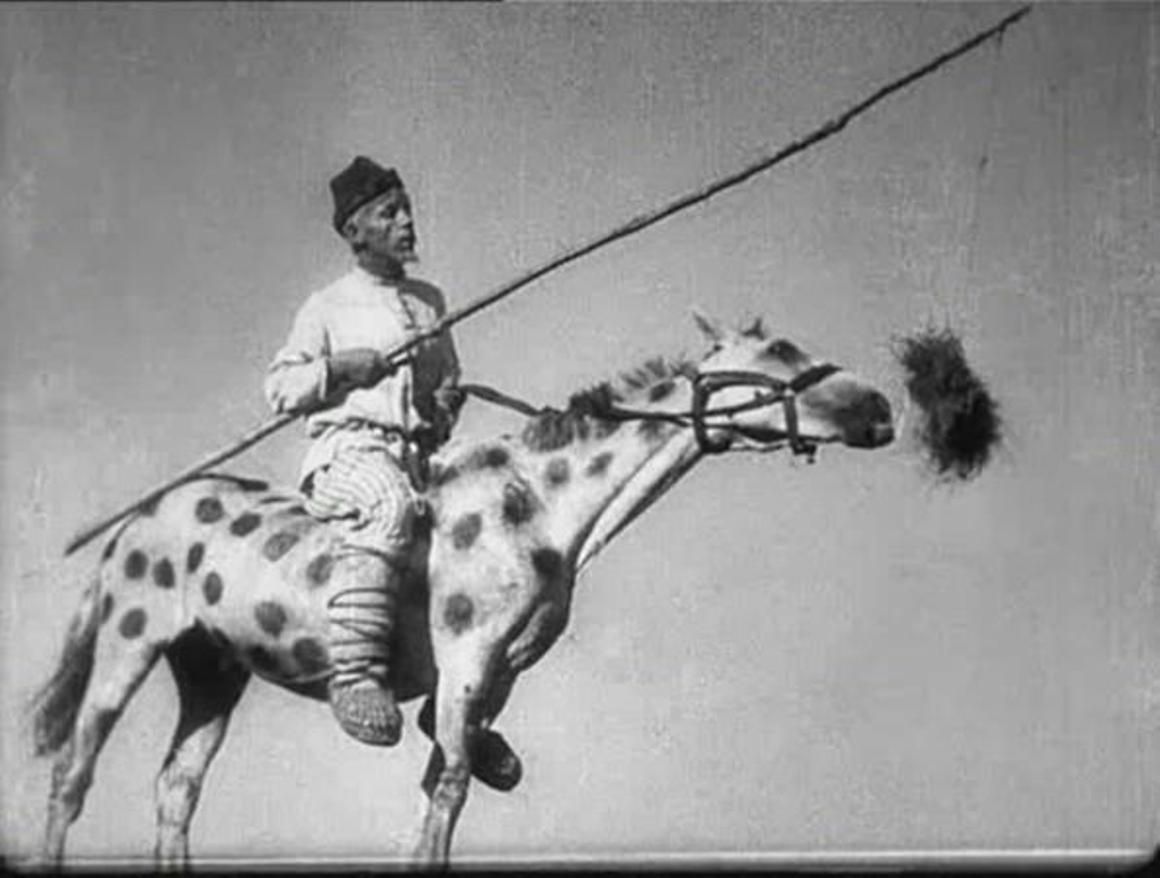

8. The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924)

Although cinephiles might have heard the term ‘Kuleshov Effect’, many might not have seen a Kulsehov film (a lot of which are also not available). Film historian and filmmaker Mark Cousins mentions how Kuleshov pioneered early editing techniques that ‘led to the idea that if the actor cannot show a thought, editing must.’ Lev Kuleshov was a fashion designer whose film workshops in the early 1920s molded the future Soviet cinematic talents, including Sergei Eisenstein, Boris Barnet, and Vsevolod Pudovkin. It was the time when Lenin famously proclaimed, “Of all the Arts, for us cinema is the most important.”

Made in the year Lenin died, The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks was an amusing propaganda feature, which incorporates the American silent comedy techniques as well as the Soviet cinematic traditions. The plot follows an American businessman, Mr. West (Porfiri Podobed – reminds us of Lloyd’s ‘Glasses’ characters) preparing for a trip to Russia to experience the land of Bolsheviks. Unfortunately, the only point of reference for Mr. West about Bolsheviks is a New York magazine which is full of terrifying caricatures. Therefore, Mr. West recruits Jeddy the Cowboy (played by renowned Russian silent filmmaker Boris Barnet) as his bodyguard. Of course, the cowboy comes equipped with gun, hat, and even a lasso.

Once in Russia, Mr. West’s briefcase is stolen and his bodyguard is separated from him. The briefcase is brought to Zhban (Vsevolod Pudovkin – another leading film-maker of Soviet silent cinema) and his gang of swindlers. Zhban hatches an elaborate plan to extract more dough from Mr. West by playing up with his preconceptions about Bolsheviks. Meanwhile, the gun-toting Jeddy runs amok and starts interrogating random people walking in the street, until he comes across Ellie (Vera Lopatina), a friend and an American expat.

Related to Best Soviet Silent Comedy Films: Kin-dza-dza! [1986] Review – An Extremely Amusing Soviet Sci-Fi Cult Classic

The history of Cold War is so extensively discussed that we can sometimes forget that the tensions between America and Russia existed long before that. The American intervention during the Russian Civil War would have been a fresh memory at the time. But Kuleshov’s silent comedy, despite the prism of propaganda, kind of extends its friendly hand to their counterpart, asking them to not perceive the Soviets through preconceptions. Apparently, the characters are built out of stereotypes. But the ‘other’ was not portrayed as the ‘enemy’ which was common in the later decades of Soviet and Hollywood cinema. Though Mr. West is naïve and behaves ridiculously, there’s enough sympathy for him.

Moreover, the amalgamation of various cinematic influences – American, Pre-Revolution, and Early Soviet- bestows relentless energy to the narrative. The later years’ Soviet silent comedies were so inventive and distinctly Russian that Kuleshov’s comedy may seem to lack the vitality. Still, this is a chuckle-worthy stuff from early Soviet cinema.

Watch The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West on YouTube

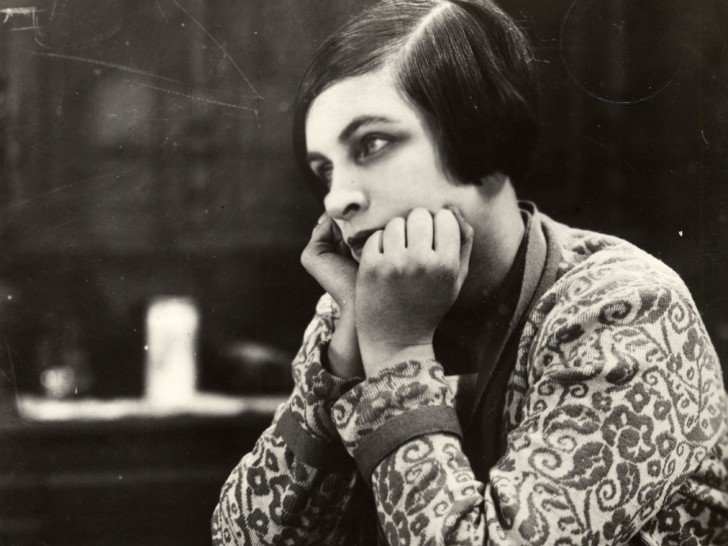

7. The Cigarette Girl of Mosselprom (1924)

Yuri Zhelyabuzhsky’s light-hearted silent comedy surprises us by not being a strict propaganda feature. Yes, it has an oleaginous, pipe-smoking, fat American capitalist character, and makes a hilarious critique on the capitalists in its opening scene. But Zhelyabuzhsky’s film largely revolves around the titular street vendor character, Zina (Yuliya Solntseva) and her three hare-brained male suitors, including the aforementioned American named Oliver MacBright. Furthermore, The Cigarette Girl of Mosselprom was largely shot on location, unhurriedly taking in the sights and look of 1920s Moscow. Needless to say, the film was criticized for not focusing on the class-consciousness.

The Cigarette Girl of Mosselprom may not be as innovative as the works of Sergei Einsenstein or retain the mischievous streak of Boris Barnet. Yet, its straightforward narrative has incorporated lot of the avant-garde elements to effectively enhance the entertainment quotient. Moreover, the characterization of Zina is intriguing. She is hardheaded, scoffs at the idea of marriage, and looks to secure a line of work. Zina does fall in love with a young cameraman named Latugin (Nikolai Tsereteli) and there’s the conventional happy ending. But there are moments when Zina feels that no one really gets what she wants. In fact, her three male suitors’ eccentric behavior – though played for laughs – evokes frustration in Zina.

Related to The Cigarette Girl of Mosselprom: Loves of a Blonde [1965] Review – When Political Practices Invades Youthful Romantic Impulses

At times, in attempting to play up the slapstick elements, the narrative moves away from Zina and focuses on the subplot involving Nikodim (played by popular Russian comedian Igor Ilyinsky), a silly office worker also attracted to Zina. Nikodim’s antics and tantrums purely belong to Chaplin’s territory. However, the film gets more delightful whenever Yuliya Solntseva is on-screen. Particularly, the costumes Solntseva wears as Zina the cigarette seller looks modern and marvelous. Solntseva became a star actor in the same year with the release of Protazanov’s groundbreaking sci-fi ‘Aelita’. Few years later, she married the internationally acclaimed Soviet filmmaker Alexander Dovzhenko and directed films alongside him.

Through Latugin’s character, The Cigarette Girl of Mosselprom also comments on the politics behind film-making and even gets a tad self-reflexive, which is something unexpected from a Soviet silent commercial cinema. Overall, it’s a familiar love story with distinctive Soviet aesthetics.

Watch The Cigarette Girl of Mosselprom on YouTube

6. Chess Fever (1925)

Vsevolod Pudovkin’s 28-minute Chess Fever is perhaps the most well-known Soviet silent comedy and truly the most hilarious one too. And Pudovkin incorporates the sense of humor through the editing revolution and distinct formalism which by then have already gained international renown. However, it isn’t a work of propaganda. But rather a lighthearted entertainment uproariously capturing the Soviet people’s chess obsession of the time. Vladimir Fogel plays the chess-addicted hero. It’s his first major role and the popularity of it turned him into a star-comedian of the silent era alongside Igor Ilyinsky. The hero’s obsession with chess remains an impediment to his love life.

The heroine (Anna Zemtsova, Pudovkin’s wife) not only hates the attention her fiancé gives to chess, but also detests chess since it’s the only thing being played everywhere. In one funniest scene, the enraged heroine throws out all the chess items the hero owns. Each item lands upon different people in the streets, from a beggar to a policeman, and they gleefully engage themselves in the game. At one point, the Cuban chess champion Jose Raul Capablanca makes an appearance. The encounter facilitates the heroine to realize the pleasures of chess.

Related to Best Soviet Silent Comedy Films: 10 Uplifting World Cinema Movies for the Family

Written and co-directed by Nikolai Shpikovsky, the influence of American slapstick comedies is obvious. Yet Pudovkin’s flashy fast cutting (he was the editor), unconventional framing and juxtapositions integrates more pizzazz to the picture. Pudovkin’s style is self-assured here, and it got all the more better in his trilogy of films on ‘the revolutionary struggle’: Mother (1926), The End of St. Petersburg (1927), and Storm Over Asia (1928).

If you watched the Netflix’s The Queen’s Gambit (2020), you might have already learned a thing or two about Soviet fixation with chess. In fact, in the aftermath of 1917 Russian Revolution, the chess fever swept the nation. The state-sponsored chess program began in the 1920s, and the Communist Party wanted to get rid of elitism associated with chess [4]. The Party viewed chess as a culturally important component for the proletariats, and also believed that the game would nurture certain attributes within military recruits and the Party members. Did it really nurture something? That’s up to debate. But it’s really interesting how the Soviet rule placed chess in its cultural front.

Stream Chess Fever on YouTube

5. The Girl with the Hat Box (1927)

Boris Barnet’s lively rom-com mixes slapstick, screwball conventions of silent era with minutiae of everyday life in Moscow. The charming Anna Sten plays Natasha, a young woman who lives with her grandfather in a small-town outside of Moscow. They both make their living by engaging themselves in millinery. Natasha takes the high-fashion hats to the Moscow shop of a bourgeois couple. Madame Irene who owns the hat shop has registered a one-room apartment above the shop under the name of Natasha. Since Natasha prefers to stay with her grandpa, the set-up is to evade the scrutiny of housing inspectors. The extra room is either used by her nitwit husband or to entertain their guests.

In one of her trips, Natasha encounters a freezing, penniless student named Ilya (Ivan Koval-Sambrosky). Deeply feeling for his predicament, she comes up with the idea of contract marriage. After the trip to the registrar’s office, Natasha takes Ilya to her allotted room above Madame Irene’s shop. Naturally, chaos and conflict ensues. The opening title of The Girl with the Hat Box mentions that the film was made to propagandize state loans aka the national lottery. Natasha receives one ticket – thought to be unworthy -from Irene’s husband instead of her wages. Of course, it becomes a ticket to ‘happiness’.

Also, Read: 25 Feel-Good Movies and where to watch them

This is one of the most popular as well as time-worn tropes in rom-com. Yet Barnet’s remarkable direction brims with energy, fascinating images, and quick action. There are lots of shots of Moscow’s wintry landscape, cramped railway station, and people busily moving about the icy streets. Moreover, the very Soviet themes of tax evasion and housing shortage water down the romantic conventions a bit, giving some insight into life in that era. In fact, Barnet’s supreme use of locations, space, and Anna Sten’s springy screen presence makes this a more delightful experience.

Watch The Girl with the Hat Box on YouTube

4. Happiness (1935)

Happiness was director Alexander Medvedkin’s most popular work. A staunch supporter of the revolution and Bolshevik faith, Mr. Medvedkin nevertheless ran into trouble with censorship, Stalinist purges, and Soviet totalitarian legacy. The film-maker was re-discovered in the 1960s when ‘Happiness’ was screened across Europe. The French documentarian and multimedia artist, Chris Marker was among those who championed the film, and later developed a friendship with Medvedkin [5]. In 1992, Mr. Marker made The Last Bolshevik. It eloquently profiled the life and works of Alexander Medvedkin.

Happiness engrosses us right from the opening sequence: impoverished peasant family watches through the fence hole at a wealthy landowner sedately sitting under a tree, and having dumpling cakes. The cakes magically leap into his mouth. When the starving old peasant dies, trying to steal the cakes leaving his family more in debt, the grandson Khmyr swears to find happiness. He and his wife Anna struggle to cultivate crops in their meager agricultural land. But when they have a bumper harvest, the couple is swindled by tax collectors, merchants, and further harassed by priests. Later, Khymr and Anna join the Collective Farm. But Khymr still remains a loser though his wife emerges as a strong, tractor-driving state-farm worker, and asks Khymr to man up.

Related to Best Soviet Silent Comedy Films: Welcome, Or No Trespassing [1964] Review – A Marvelous Soviet Camp Comedy

Happiness may not sound like a comedy at all. Medvedkin’s brilliant satirical tone, however, artfully emphasizes the absurdity of the peasant’s predicament. As with any silent comedy, the film-maker relies on exaggerated and outlandish physical comedy. Yet beneath this slap-stick surface lays Medvedkin’s political propaganda which at times slyly denounces certain traits of Stalinism. Happiness has a lot of memorable surprises, including the shots of army men wearing strange masks, and nuns wearing transparent tops (the religious figures in the narrative are scathingly criticized and caricatured). Furthermore, the absurd scenario that follows when Khymr proclaims he is going to commit suicide remains unaffected by time.

Similar to many Soviet silent films, Happiness also deals with proto-feminist themes. Anna is depicted to have readily embraced the winds of sociopolitical change and turns herself into a proud member of the kolkhoz. In reality, women actually played an important role in the resistance to Stalin’s brutality of collectivization.

Stream Happiness on YouTube

3. My Grandmother (1929)

Kote Mikaberidze’s jaw-dropping experimental silent comedy My Grandmother (1929) could be described as a freewheeling satire on the slothful, complacent nature of the bureaucrats. It doesn’t have a coherent plot, although it follows a laid-off incompetent pen-pusher (Aleksandre Takaishvili) attempting to gain employment by find himself a “grandmother”, i.e., an influential bureaucrat willing to offer a recommendation. And director Mikaberidze zeroes in on this storyline after spending nearly one-third of the narrative’s length to farcically detail the nonsensical antics of Soviet bureaucrats. But the way it plays with form, vigorously utilizing every visual trick available at the time, keeps us absolutely enthralled.

From avant-garde camera angles, stop-motion animation, puppetry to rapid cuts, freeze frames and montages, Mikaberidze has great fun in concocting this fantastical projection of bureaucratic reality. The shoddy office practices would definitely bring to mind Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967). The comedy doesn’t simply rely on slapstick. The central character loses his job after his laziness is lampooned in a newspaper in the form of a cartoon. The information is imaginatively conveyed by visualizing that the bureaucrat getting impaled by a giant flying pen, implying that he is roasted by a newspaper journalist.

Related to My Grandmother: The Firemen’s Ball [1967] – A Bewitching Satire on Human Frailties and Political Groupthink

Although Mikaberidze kept in line with the state propaganda by eventually lionizing a proletariat worker who ascends to the top position and calls for ‘Death to Red Tape’, the regime banned it. Probably appalled by the hysterical nature of the comedy and due to its incoherent political message. The suffocating socialist realism cinema of Stalin’s era was intent on selling healthy role models. Here the characters not only have a negative image, they also revel in absurdity. Even so, we actually enjoy this absurdist humor; for instance the remarkable and unforgettable dance sequence of the bureaucrat’s wife (a fantastic Bella Cherneva) and his little daughter. Mikaberidze might be trying to mock the bourgeois pettiness of the family (the captions suggest it too). But the infectious visual energy puts us in the mood for merriment.

The proletariat boss is nothing but menacing. He certainly doesn’t seem to have that happy ‘revolutionary spirit’. Therefore, it’s no wonder that despite the appeasing final message, the film’s convulsive formalism annoyed the regime. My Grandmother was restored in the 1970s. There’s an English narration version with Beth Custer’s jazz score. However, I’d recommend the one without the narration and intertitles. This version features the sublime music track of Georgian composers Nika Machaidze and Natalie Beridze which perfectly complements the extraordinary on-screen energy.

Watch My Grandmother on YouTube

2. The House on Trubnaya (1928)

Boris Barnet, a professional boxer who later turned into acting, screenwriting, and directing, is one of the early geniuses of Soviet Cinema. Some critics stated that though Mr. Barnet moved out of the boxing ring, he still pulled punches on-screen. The House on Trubnaya is an important satirical comedy, set in Moscow, during the period of New Economic Policy (1921-1928). Blending slapstick and pathos, Soviet-State ideology and effusive imagery, The House on Trubnanya chronicles the injustices suffered by a naïve rural girl Parasha Pitunova (Vera Maretskaya) at the hands of a petit-bourgeois hairdresser, Golikov (Vladimir Fogel).

Mr. Barnet incorporates aspects of slapstick cinema while meticulously packaging it with the political messaging that includes Parasha eventually arrogating her proletarian rights by joining the domestic workers’ union. Though the narrative is embedded with Soviet propaganda or mythmaking, The House on Trubnaya is compulsively watchable for its intriguing formal aspects. The narrative employs the then avant-garde aesthetics to emphasize the supposedly transcending nature of the Soviet State as the emerging class-conscious proletariats are standing up against the bourgeois exploitation. Moreover, as the Sense of Cinema article pensively observes, “…this is a happy Moscow in its last gasp of the NEP and on the verge of plummeting into codified pageants, structure and fear” [6].

Also, Read: Spring on Zarechnaya Street [1956] Review – An Enjoyable Romantic Melodrama of Thaw-Era Cinema

However, it is the comic set-pieces and carefully constructed mayhem that outlasts the political grandstanding. Right from the opening act that poetically depicts the dawn at Moscow, and subsequently captures the frenzied happenings at the five-story Trubnaya apartment stairwell, Barnet drives the narrative with relentless energy. With playful flashbacks, mirthful montage, and eye-catching crane shots, the film-maker swamps us with one striking visual device after another.

Watch The House on Trubnaya on YouTube

1.Bed and Sofa (1927)

Abram Room – one of the pupils of preeminent Soviet film-maker Lev Kuleshov – made Bed and Sofa (1927), a wry comedy and a psychological drama, at a time when Soviet cinema was engulfed in socialist realism and political didacticism. The film tells the tale of Liuda Semyonova (Lyudmila) living with her self-centered construction worker husband, Kolia in a basement apartment in Moscow. Liuda spends her days between household chores and idly reading magazines. Into this atmosphere of frustration arrives Volodia, a printer and Kolia’s Red Army buddy. Due to the housing shortage crisis, Kolia asks his friend to take up the sofa that’s occasionally occupied by their cat.

When Kolia goes away on a business trip, the considerate and sensitive Volodia wins over Liuda, even taking her on a plane ride. The sofa moves to the bed. And when Kolia returns back home and finds the truth, the narrative takes an interesting turn. What follows is a comically bizarre love triangle that eventually calls for the liberation of women in the new Soviet society. Apart from its sexual content and moral ambiguity, Bed and Sofa is full of formal experimentations that naturally don’t fit into the creed of ‘socialist realism aesthetics’. The suggestion of sexual intimacy between Volodia and Liuda through the playing cards was a pure ‘Wow!’ moment.

Also, Read: July Rain [1967] Review – An Engrossing Study of Society and Youth in Flux

The frankness with which Mr. Room deals his characters’ feelings and the scenario – including a casual treatment of abortion – reminded me of pre-code Hollywood features. Moreover, Bed and Sofa never reach for a compromise, eventually granting its female protagonist her agency as a woman. The film received a mixed responses from the audience of the era, negative criticism from the establishment, and even got banned in countries like Britain. Nevertheless, Bed and Sofa is one of the most significant works of Soviet silent cinema, artfully evoking sardonic laughter.

Watch Bed and Sofa on YouTube

Notes:

- ‘Art Into Life’ – The Radical History of Soviet Silent Cinema, Silent-ology

- The Story of Film, Mark Cousins, Pavillion Books, published September 2006.

- A Kiss From Mary Pickford, Richard Hildreth, San Francisco Silent Film Festival

- Red Squares, Christopher Beam, Slate, Sep. 2009

- Chris Marker, Notes from the Era of Imperfect Memory

- The House on Trubnaya, Greg Dolgopolov, Senses of Cinema, Sep. 2012

And of course very grateful to Wikipedia, IMDb, Letterboxd, and YouTube!