“It never ceases to amaze me how interesting everyday life really is. There are an endless number of human truths.” This statement from Belarusian journalist Svetlana Alexievich [1], who is known for narrating history ‘from below’, seems to allude to the emotional world of Marlen Khutsiev’s cinema. He is a forgotten Soviet master of the Thaw generation, who revitalized Soviet cinema right from his directorial debut Spring on Zarechnaya Street (1956). Khutsiev’s heavily censored yet undeniable masterwork I am Twenty (1965), and the equally brilliant companion piece July Rain (1967) deeply explored the emotional contours of 1960s Soviet Youth. Both the films are mesmerizing formal experiments that will surprise you with its emotional acuity, and furthermore doubles up as a love letter to Moscow and the Muscovites.

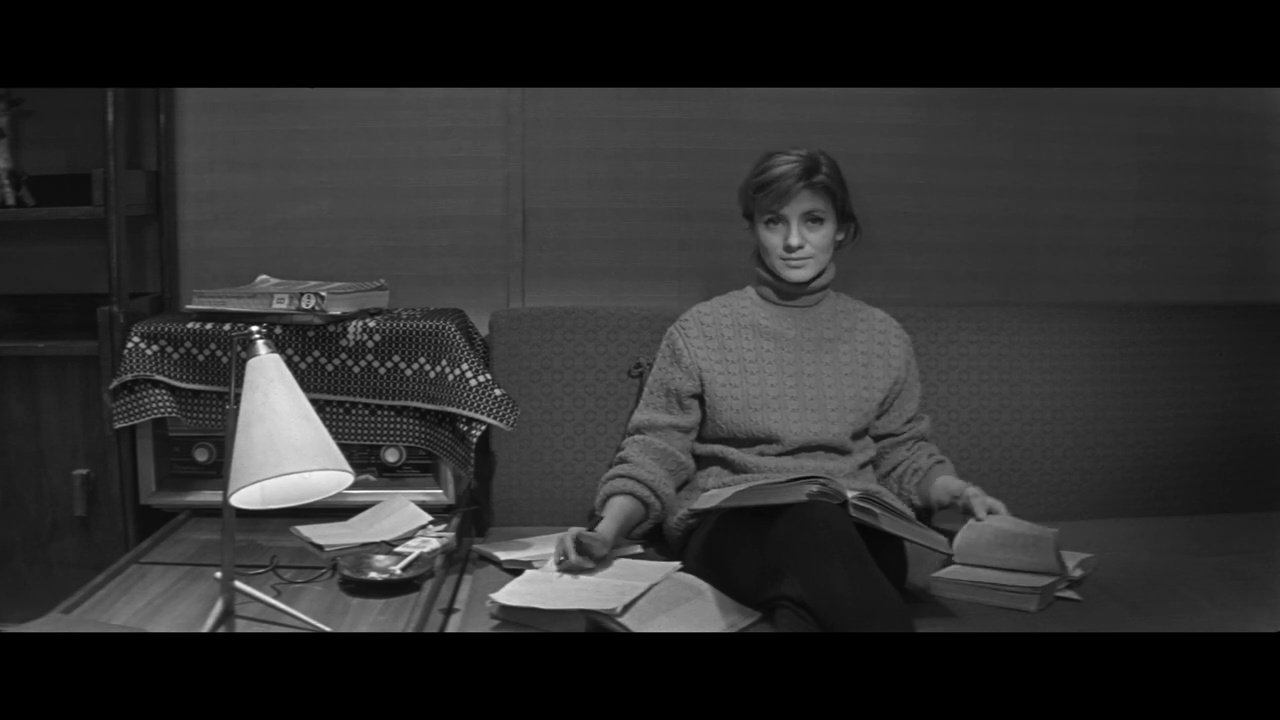

A city portrait and a nuanced study of modern urban alienation, July Rain evokes feelings that are universal and timeless. The protagonist, Lena (Evegeniya Uralova) is an intellectual, independent woman in her late twenties. Her boyfriend Volodya (Aleksandr Belyavsky) is an ambitious and a promising scientist. Lena works at a printing press, and is burdened with questions that might naturally trouble a person of that age: should she go to grad school or get married to Volodya? He has his own concerns like finding a publisher for his research paper. Despite the warmth one feels in their embraces and walks together, the highly mechanized life indicates an emotional crisis lurking beneath. Lena’s picnics and get-togethers with Volodya’s fellow suburban careerists strongly underline the pervasive ennui and alienation felt by everyone. It’s more play-acting than living.

Related to July Rain: Courier (1986) Review – A Poignant Coming-of-Age Drama Set in the Twilight of Soviet Union

They listen to Western music, wear stylish outfits. Most of them have grown up in post-war Russia, in a relatively liberalized Moscow. Nevertheless, they are affected by the very modern malaise: melancholy, loneliness, and vague existential angst. Marlen Khutsiev interleaves the narrative with a brooding uncertainty which might resonate with youths across culture and time, but also happens to be Soviet specific. The year 1967 was an important year in Soviet history. It marked the decisive end of Soviet Thaw – a period of political and cultural liberalization. Leonid Brezhnev who succeeded Khruschchev (in 1964) cancelled most of the reforms and ushered in a era of stagnation and political repression. When Soviet and Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968 to put an end to the Prague Spring, the gradual march towards liberalization came to an abrupt halt.

In July Rain, such unspoken sociopolitical crisis collides with the psychological conflicts of the characters. But it is to Marlen Khutsiev’s credit that the emotional interiority of the central character and her dilemma can profoundly speak to contemporary audiences too. Like many of us, Lena has benefitted from a radically changed social and cultural space, and yet it’s hard to be positive that a new future awaits her. But to live – however elusive the meaning and purpose of it is – we need to believe in an awakening that would bring in the ‘interior’ change of seasons; the ‘spring’ that dethaw one’s emotional frigidity. Mr. Khutsiev reaches for and believes in human warmth that he ambiguously as well as lyrically ends Lena’s tale by literally making her walk into the dark pedestrian tunnel and emerge out to a bright spring day.

In this final sequence, Khutsiev studies the faces of old and young gathered at Kremlin square because it’s Victory Day (to commemorate the surrender of Nazi Germany). Lena walks with resoluteness and relaxed look, and loses herself into the crowd. The camera, however, voyeuristically looks at people of different age-groups. The very last shot is that of a kid looking out from an adult’s elbow. These shots don’t seem to have a definitive political purpose to it. The youngsters and kids are questioningly looking back at the camera than the self-assured war veterans, possibly hinting at the Soviet society caught at the crossroads. But by guiding us through the expansive space bustling with humans, Khutsiev breaks down our innate cynicism and indifference for people, even making us crave for such human warmth.

In his time, Marlen Khutsiev was criticized for the ambiguity in his narrative or for often evading the ideological norms of Soviet apparatus. On a more general note, critics find fault with Khutsiev’s fragmented plot structures. But I am Twenty and July Rain isn’t a typical filmic depiction of alienated youth and generational disconnection. The aural-visual constructions here are much more complex that it confines us to the agitation and excitement prevalent in the rapidly changing society. In July Rain, Khutsiev’s juxtapositions – in terms of image and sound – engages our senses in an unparalleled manner.

The film’s long opening, quasi-documentary sequence moves through Moscow’s busy shopping streets (probably shot from a moving car) as the camera briefly follows few persons in the crowd (the camera zooms in to follow few in the crowd and then zooms out), before settling on our protagonist. Khutsiev juxtaposes the image of busy Moscow streets with Renaissance-era paintings; the particular meaning of it is lost on me. However, later we learn that the printing press where Lena works reproduces the Renaissance paintings on a mass scale. I can vaguely piece out the metaphor involving artistic painting with the increasingly mechanized modern-era, but it’s something I’d like to contemplate more on the re-watches. But the aural juxtaposition in this opening sequence is also equally exciting. As Khutsiev’s introduces his Moscow we hear the changing signals of radio station, and we listen to different music, soccer game, and news broadcasts. When the camera finally zeroes-in on Lena who is walking among the crowd, music – overture of Georges Bizet’s Carmen – stably starts flowing.

Also Read: Loves of a Blonde [1965] Review – When Political Practices Invades Youthful Romantic Impulses

Moreover throughout July Rain, Khutsiev’s focus on the domestic settings and the city squares tend to highlight the life of young generation in private and public spaces that has become alien to them. Nevertheless, at times solitude within a confined space does provide the essential relief for Lena. This is expressed through the series of unfeigned phone conversations she has with a stranger, who bestowed upon her a gesture of kindness during the July rain.

Soviet cinema often tends to reach for something decidedly monumental. Though Khutsiev’s graceful use of dolly and crane shots depicts the all-inclusive city brimming with energy (I can’t forget the phenomenal ‘May Day’ parade scene in I Am Twenty), July Rain is deeply personal. It comes close to perfectly capture the state of a soul during a particular period in life.

Marlen Khtusiev strikes such strong authentic note in reminding us of the not-too-happy days of love when disillusionment and frustration envelopes us. Nevertheless, July Rain ends by subtly emphasizing that there will be a silver lining; a beautiful spring day and some human warmth to savor.

★★★★

Watch the full movie on YouTube:

To discover more such hidden gems of Russian and Soviet Cinema please visit: Russian Film Hub

Note:

- Secondhand Time, Svetlana Alexievich, Juggernaut Books, July 2016

![Lorelei [2021] Review: A striking fairytale interconnected by fate and burning desires](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/LORELEI-2021-Review-768x413.jpg)

![We are Living Things [2022]: ‘Slamdance’ Review – Aliens searching for Aliens while dealing with existential alienation](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/We-Are-Living-Things-Slamdance-768x432.jpg)

![Aliens of the Deep [2005] Review: The Search for Life Beyond Begins Below](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/aliens-of-the-deep-2-768x432.jpg)

![Climax [2018]: ‘MAMI’ Review – The Greatest Cinematic Experience of the Year](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/climax_still_01-768x384.jpg)