The screen slowly fades in, and the viewer is introduced to bright sand figures from Tibetan folklore, all belonging to Mandala art. Philip Glass’ soundtrack kicks in, deep hums, both epic and meditative in nature, transport you to the quiet mountains of Tibet, and you feel a connection to a culture, to a place you have only heard about. A serene, almost spiritual face of a sleeping child is revealed as our camera slowly pulls back. Lhamo, two years old, is the future protector of a region with a history of over 2000 years. The bearer of a legacy, a legacy which guides its people and encourages them to practise non-violence in a region, vast and turbulent as Asia.

The intro text reminds us, “The sons of Genghis Khan called the Dalai Lama ‘Ocean of Wisdom,’” and Scorsese’s 1997 film “Kundun” interprets that legacy through early childhood and emotional upheaval rather than political grandeur. The film traces the life of a boy taken to the ancient Potala Palace, separated from his family to become a monk, and ultimately the leader of Tibet—an origin story shaped as much by longing as destiny. All at a time when the world outside is going through its upheavals, be it the devastating Second World War, its big neighbour China tearing itself apart in a civil war, or the two nuclear bombs which made people believe in man’s capacity to bring hell on Earth.

Martin Scorsese was not the natural choice for such a movie. As the movie’s screenwriter, Melissa Mathison puts it, “Scorsese was not even on the list of directors provided by the studio”. The Italian-American director “made his bones,” as many say, in his classic mob movies, with works such as “Mean Streets,” “Goodfellas,” and “Casino”, capturing the mafia lifestyle and its many downfalls. Scorsese’s direction reshapes the film into a visual revelation, preventing it from collapsing into a studio-assembled “greatest hits” biopic, the kind Hollywood seems almost too eager to mass-produce these days.

Visions and prophecies play a huge part in the movie as well. With the help of classic visual techniques and beautiful frames and shots provided by the legendary Roger Deakins, elements of mysticism translate beautifully to the screen. Heartfelt scenes, such as when the young Lhamo has to choose things, such as a stick and glasses, all belonging to a previous reincarnation, the 13th Dalai Lama kept in front of him to confirm the Buddha’s rebirth, are both haunting and beautiful.

Reting Rinpoche, the regent whose vision led to a search party for a boy in a remote village bordering China, meets the young Lhamo, and the mastery of Scorsese kicks in. Montage of a lake amid the high Himalayan mountains, sands of Mandala art, extreme close ups of Reting’s eyes, flags on top of Lhamo’s house and Reting’s question of “Hope it was not too long a wait, Kundun?” take you on a journey laced with prophetic visions of future, interconnectedness with the past and the politics which comes with it. “Kundun” in Tibetan means “The One Before Me” and is one of many terms to refer to the honoured one.

Also Read: 7 Most Underrated Martin Scorsese Films That You Need To Check Out

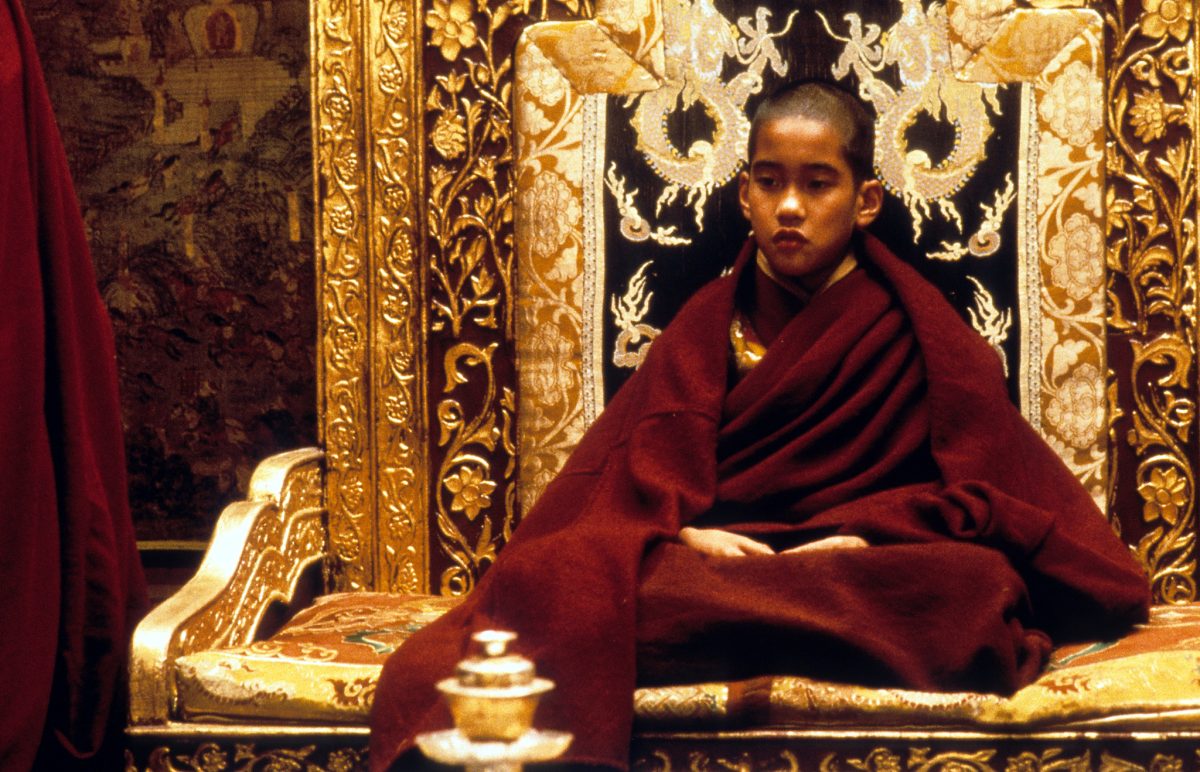

“In Search of Kundun”, a documentary chronicling the making of the movie, Scorsese emphasizes the human element of the story,“ The shots have been designed such that the audience also focuses on how a child would feel in such a situation…the loneliness…the isolation”. The chosen 14th Dalai Lama, a small child, peeks his head out as his retinue leaves the ancestral home in which he was born. He takes a look at his neighbours who bow their heads in reverence, at antelopes running on steep slopes, and at birds flying in the great blue sky. Kundun’s journey has begun.

The film had to be shot in Morocco because permission to shoot in India was never given, which went on to impact many aspects of the movie. However, Scorsese was adamant about capturing the authenticity of Tibetan culture. The movie’s creative team would meet with the Dalai Lama many times to discuss nuances such as set design and chronology of events, and even cast many of his relatives. His niece, Tencho Gyatso, praised for her deeply natural and emotional acting in the movie, played the spiritual leader’s mother, while Tenzin Tsarong, his great-grand nephew, played the adult Kundun.

The set design also adds to the cinematic value as the settings, the very surroundings, become a character and get a life of their own. However, as Scorsese says, the movie’s focus is not merely on faith and Buddhist principles, but on people. Lhamo visits his father’s funeral, a powerful sequence in which Tibetan death rites leave viewers awestruck. Traditional bodybreakers disassemble the human vessel, as monks keep the vultures away with sticks, presenting sky burials in a dignified manner and symbolising the Chinese invasion.

The 14th Dalai Lama grew up amid rising tensions with China, temple politics which saw his once teacher and regent, Reting, dying in prison, and his ambition of modernising his isolated country. To get around the problem of showing the entire invading forces of the Chinese Communist Party, Scorsese simply covered the Tibetans and other extras on the set with dirt, goggles, and uniforms. The results are mystifying: soldiers carrying paintings of Chairman Mao, followed by trucks and artillery.

“They have taken away our silence”, Kundun laments as loudspeakers blare CCP songs and propaganda on the streets. The Chinese invasion plays a huge part in the movie and surely does not portray China in a positive light. The film is interspersed with radio announcements of “ Benevolent Chinese forces driving away imperialist forces from Tibet”, even as reports of Chinese brutalities are discussed in the temple halls.

Chinese generals stride into the frame with an air of entitlement, issuing demands for food without acknowledging the famine consuming the region, ordering the surrender and absorption of Tibetan forces against overwhelming Chinese firepower, and even insisting on a ban on songs that mock the invaders.

It is rather surprising that Walt Disney, the parent company of Touchstone Pictures, which produced the movie, would choose to greenlight such a project. The film faced serious backlash in China amid calls that it should not be released. Disney, the corporate giant and now the killer of favourite franchises such as “Star Wars” and “Indiana Jones,” was forced to take a step back and limit its release.

The result was a box-office bomb, which failed to recoup its budget. However, even during filming, the cast and crew knew the importance of the work. The depiction of the traditional Tibetan lifestyle, its rich tapestry of tales, and its beautiful ethnic wear stunned even the Tibetan natives who were cast in various roles in the movie.

Must Check Out: 15 Best Martin Scorsese Pictures

As teary-eyed Tencho Gyatso recalls “In Search for Kundun,” a young Tibetan woman confessed to her that she did not know her culture was so rich with its elegant festivities. The masked dances and oral storytelling of Losar, the echoing prayer festivals within the vast halls of the Potala Palace, and the solemn grandeur of the Dalai Lama’s enthronement usher a new generation of Tibetans toward their inheritance, conveyed not through sterile newsreels but through sequences shaped by emotion, craft, and cultural pulse.

The film also encapsulated the politics of its time, be it the young Kundun watching news reports on the atomic devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki or his meeting with Mao in the film’s final act. Natural, well-crafted dialogues flow between the characters as the viewer is immersed in the movie’s world. The movie’s form is much more rhythmic than Scorsese’s other works, almost adding its own poetry to the tale.

The final act of “Kundun,” where the young Dalai Lama flees to India, aches because it doesn’t announce itself. There’s no swelling score instructing you how to feel. It’s a child leaving pieces of himself behind, one goodbye at a time, crossing into a future that looks like fog, distance, and maybe a life he never truly signed up for. Tibetans cry his name from the ground he can’t turn back toward, arms outstretched for a return that hangs in the air, unanswered, unbearable. Komasa lets his past flicker through these moments — childhood visions, faces, fragments of home — the kind of memories that soften nothing, yet might be the only warmth he carries forward.

When production wrapped, the crew was pulled into traditional ceremonies — masked dances, celebrations, collective gratitude that felt more like an embrace than a finale. It belonged to the film without needing to be in it. The audience the film reached had already lived the story once, off-screen: fleeing Chinese retaliation after the 1959 uprising, scattering into a world that kept demanding they forget where they came from.

The longstanding tensions between tradition and modernisation, between Chinese atheism and Tibetan religiosity, between an older Mao and the young Dalai Lama come to the fore in this cinematic piece. The political push-and-pull around the movie affected its finances, predictably, almost routinely. What it carries, what it preserves, what it quietly gifts its audience survives elsewhere — in exile communities seeing the shape of a life, a culture, a homeland they’re still trying to reach again, even now.

![One Second Champion [2021]: ‘NYAFF’ Review – A traditional Boxing tale with style & flair](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/One-Second-Champion.jpeg)

![Lucky Chan-sil [2020] Review: A movie producer in an existential fix](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Lucky-Chan-sil-Movie-Review-highonfilms-3-768x512.jpg)

![Hit Big [2022] ‘PÖFF’ Review – A Comedic Crime Caper with Shabbiest Characters](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Hit-Big-2022-768x432.jpeg)