Diego Fuentes’s “Matapanki” (2026) is filled with the kind of youthful ferocity that you can usually trace in a filmmaker’s debut project. It’s evident in films like Darren Aronofsky’s “Pi,” Damien Chazelle’s “Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench,” and Christopher Nolan’s “Following,” the latest of which also took its first steps at Slamdance. All three films are shot in black and white and employ an aesthetic approach that may not yield a result as refined as their later works. People may even have some valid grounds to criticize their scripts or execution. Yet, they hold a special place in their respective filmographies, owing to their irresistible charm or vitality.

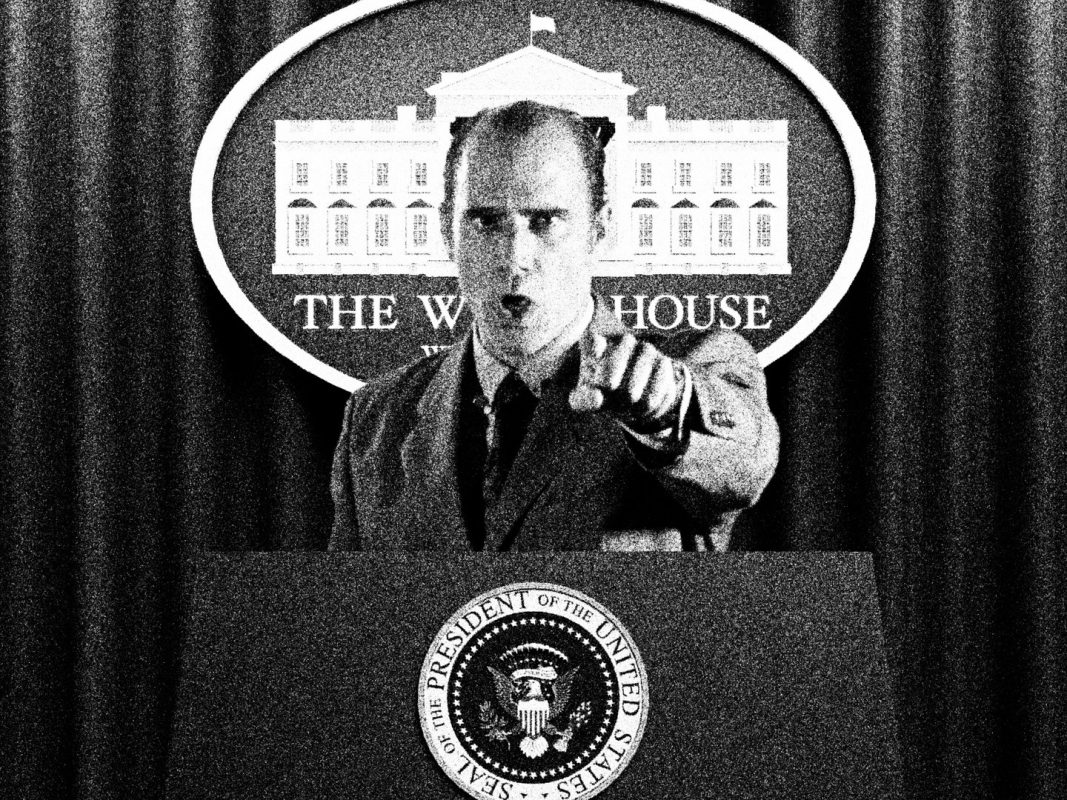

Fuentes’s debut is similarly exuberant and reckless, even if it may not meet all the criteria to make it a ‘perfect’ project. It feels almost irrelevant while watching his film because he imbues it with the relentless energy of headbanging rockers. It’s the kind of energy Aronofsky hoped to capture in his latest film, “Caught Stealing,” backed by a grungy score from the anti-monarchist punk-rocker Brits from Idles. While he occasionally succeeds in that regard, Fuentes excels in presenting that vibrant, anti-establishment sentiment by bringing it to the forefront. He makes it a central theme in his script, as it guides his protagonists while they move past the inciting incident.

The film revolves around Ricardo (Ramon Galvez), a young man sharing a small apartment with his grandmother, surrounded by posters of everything that intrigues him. After a brief visit from Claudia (Antonia McCarthy) and Mella (Diego Bravo), the former of whom questions him about her books by Camus and Fahrenheit, he heads out to rave at a rock concert. While there, he stumbles upon a bottle of strange liquid that messes with his mind. Within moments, he crashes on the floor, terrified of what’s happening to his body. While trying to run away from that pain, he bumps into two men and gets hurt, but receives no help from either.

The next thing he sees is a world brightly lit with a sharp, morning glare that reveals his miserable state. He is half-naked with clothes torn apart, wandering the streets in a foggy state. Along the way, he hears the news about the concert being illegal and ending with a terrible explosion. After that, he embarks on a journey defined by this peculiar incident, believing the strange liquid gives him superpowers and is related to the said explosion. Claudia and Mella join him in his boisterous journey, which follows the usual tropes of moral awakening, guided by a well-known principle: ‘With great power comes great responsibility.’

The script quickly builds into a common-man-turned-vigilante arc that is central to almost every superhero narrative. What sets Fuentes’s film apart is the cultural specificity he manages to capture within the genre constraints, while expanding its narrative scope to reflect a geopolitical conflict.

Set in Chile, he presents it through the lens of a Latin American youth expressing their rage and disbelief with the authorities that try to stay within the good graces of imperialist forces. That’s where the titular liquid becomes not merely the means to give superhuman abilities, but for the authorities to use those abilities to fulfill their twisted, self-serving motives. That’s why the central dilemma is nearly identical to the one of Sentry’s character in “Thunderbolts.”

Yet, unlike that film, the drama in Fuentes’s script doesn’t present an internal conflict within the States. Instead, their representatives ignite conflict outside the country that would ultimately benefit the upper echelons of both sides. It’s a compelling premise, even if not the most nuanced or mature in its presentation. Yet, it translates better through Vicente Correa’s cinematography, which captures the grunginess of Ricardo’s world through its grainy beauty, backed by energetic rock soundtracks that amp up the energy just the right amount.

The graffiti-covered walls offer a punchy backdrop for its action scenes, which feel surprisingly similar to the comic-bookish, whimsical fights in Edgar Wright’s “Scott Pilgrim vs. the World.” Although shot in monochrome, “Matapanki” takes similar creative liberties in painting the vibrant, rebellious spirit of these youngsters as they try to break free from their shackles.

Ultimately, the film doesn’t dive deep enough into the complexities of its potent conflicts, nor does it seem intent on establishing itself as a definitive voice in exploring them. Since we don’t learn enough about the protagonist’s life before the concert, it’s hard to buy into the level of investment he shows later to fight against the power. Even if he was a rebel without a cause, the script could have analyzed his ideological roots in more detail, making his arc more believable.

Despite those issues, the film is a striking showcase for Fuentes’s talent, showing his knack for cohesive worldbuilding even while working with a modest budget. Lleyton Monteverde’s editing is another highlight, effectively presenting the punk-fueled mood that Fuentes hopes to capture.

While the film is rough around the edges and at times jarringly unsubtle, it manages to address some compelling dialectics related to the way people choose to look at violence in general — when it’s deemed permissible or is frowned upon, and how it affects our ethical understanding of the world. It’s definitely an ambitious debut with a stylistic flair that gets its point across, if a bit clumsily, by the end.

![Truth or Consequences [2021]: ‘MUBI’ Review – An Examination of Truth in the Consequence of Capitalism](https://www.highonfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Truth-and-Consequences-2020-highonfilms-768x432.jpg)

![The French Dispatch [2021] ‘BFI’ Review: A Quirky cast, stunning shots, but little else](https://www.highonfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/The-French-Dispatch-768x562.jpg)