Masculinity is so neat and smart in the old Hollywood movies, especially the ones set in the American frontier. While what we saw was a convincingly realistic version, it’s actually made by great film-makers who had mastered the cinematic craft to convince you. From the early silent film days to the recent Antoine Fuqua’s remake of “The Magnificent Seven” (2016), Western genre has portrayed masculinity in different shades. The perceived noble figures of early Western films were freed from their political notions and war-induced traumas. The protagonist would be so polite with the ‘virginal’ heroine, clamps down on the minority member of his community (and usually the minorities would be shown as drunkards with a weapon), and gun down the ‘bad’ men. These are all inconsistent virtues of our movie heroes, which commenced with all those old Hollywood movies and continue to be silently admired by modern movie-goers. You could have a field day if you are set to analyze the unceasing sexism, racial inequality, and glorification of violence in those old Westerns. In the later years, with Leone’s spaghetti Westerns and Sam Peckinpah’s unflinching visions, the uglier sides of frontier men’s masculinity were brought to light. The protagonists weren’t the typical noble men, but were painted in grey shades. The evolutionary cycle on the portrayal of the 19th century Frontier men or Cowboys in cinema, I think made a full circle with Andrew Dominik’s profound, plaintive exploration of the ‘Old West’ heroes in “The Assassination of Jesse James by Coward Robert Ford” (2007). Personally, I prefer the later year Western genre films, which are labeled as ‘revisionist’ or ‘deconstructed westerns’. However, I do love few of the gloriously hopeful and endlessly entertaining old Western films. The exemplary works from the old masters of this genre like John Ford, Howard Hawks, etc boasted cinematic depth, which heavily influenced the Hollywood film-makers of subsequent era (although topical breadth in these old films are another matter).

The conservatism themes are pretty evident in the films of John Ford and other great Western genre film-makers of the era. Ford made one of the greatest Western films titled “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”, in which he made the famous announcement: “When the legend conflicts with the facts, print the legend”. It’s an advice Hollywood follows to this day, concocting pure fictional tales with the nonsensical label ‘based on true events’. While a lot could be argued about the ideology pushed through these old tales of legends, one can’t argue about or annul the majestic vision, Mr. Ford had crafted for his cinema. On the first look, Ford’s characters might seem to be too simple. Nevertheless, the man’s genius lies in his ability to visually express the convoluted desires and emotional complexities of the characters. From “Stage Coach” (1939) to “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” (1962), the master made obligatory concessions for studio-heads and then pursued his pure, unadulterated vision, which has stayed indefinitely in the minds of movie-lovers.

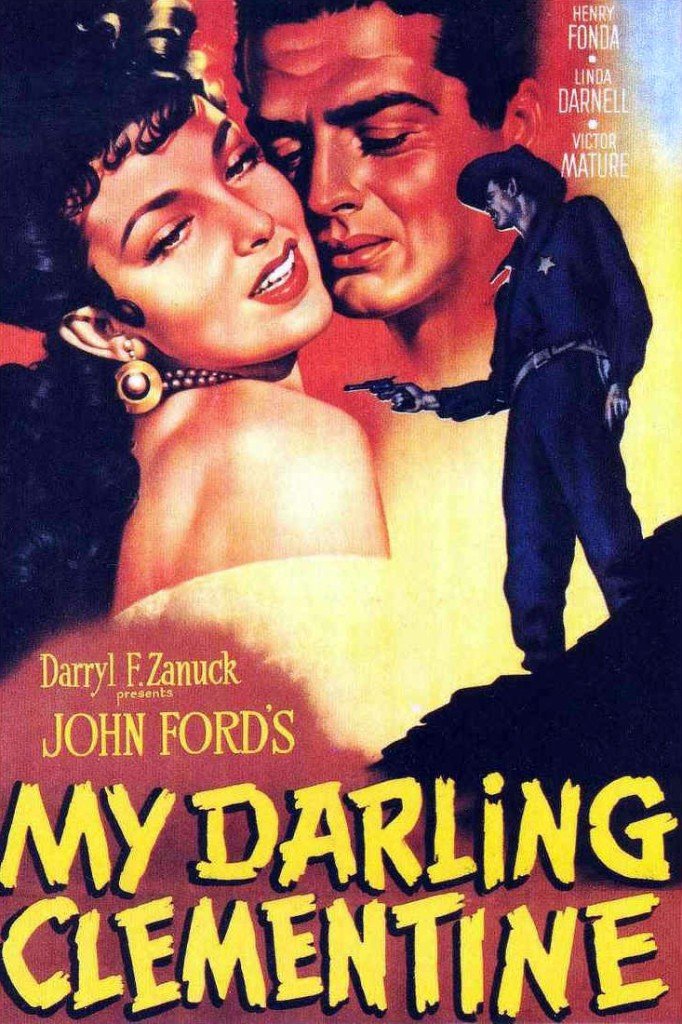

A relaxed, laid-back Henry Fonda tips back his chair on the shadowy porch, facing sun-bleached desert expanse (the plains of Arizona). It’s one of my favorite, ingrained movie images. And, Henry Fonda never looked this relaxed and cool as he was, when playing Wyatt Earp in John Ford’s “My Darling Clementine” (1946). I generally like Henry Fonda and James Stewart’s performances as ‘Western’ heroes than the proverbial tough men like John Wayne. Fonda and Stewart possessed their own distinct rhythm, which enabled them to bring something fresh to familiar Western set-pieces – shootouts, courtship, wagon chases, etc. They have also possessed an air of ambiguity, unlike other ‘Western’ heroes. Combine that with a crackling script (by Winston Miller and Samuel G. Engel), and graceful visual flourishes, you get one of the best Western movie ever made. The myth of Wyatt Earp and his famous gunfight at O.K. Corral is one of the repeatedly documented events in American Western films. John Ford had consulted the real Wyatt Earp (1848-1929) for a silent film, although his own version of Earp is pure fiction. In movies, Tombstone — uncontrolled frontier town – is shown as the battleground between Earp brothers and rowdy Clanton cowboys (good vs bad). However, in reality, it was a political battle between two opposing factions. By the time, there was a climactic showdown at O.K. Corral, both sides abused law and had their fair share of pending arrest warrants. Both Earps and Clantons were the power players, who showed utter disregard for the law. But since in movies you need a clear-cut line dividing the good, ugly, and the bad, Earp brothers are portrayed as fair, noble souls; the Clantons as irredeemably bad apples; and John ‘Doc’ Holliday (Victor Mature) as the good-hearted frenemy.

“My Darling Clementine” was the fourth Wyatt Earp movie. Paramount’s “Wild Bill Hickok” (1923), followed by 1934 and 1939 versions of Wyatt Earp story as written by Earp’s biographer in the book “Wyatt Earp: The Frontier Marshall”, released in 1931. During his later years, Earp was very careful in constructing his own legend as the man who brought peace and law to the violent Wild West. It is the myth flawlessly adapted by Hollywood and led to consistent cinematic incarnations played by Randolph Scott, James Garner, Burt Lancaster, Joel McCrea, Jimmy Stewart, Kurt Russell, and Kevin Costner. The real life account of Wyatt Earp was less flattering. He was a deputy US Marshall as well as donned the job of brothel keeper, bouncer, stagecoach guard for Wells Fargo, and gambler. Historians consider Lake’s biography as ‘purely imaginative’ or a ‘hagiography’ as it has twisted every known fact about Earp. It was one of Lake’s books that served as a foundation for the story of Ford’s movie. In the first scene of “My Darling Clementine”, Ford seems to clearly discard Earp’s real story for providing a tale of engaging conflict.

The year is 1882. The Earp brothers – Morgan, Wyatt, Virgil, and James – are seen to be passing through Monument Valley as cattle rustlers, when encountering old man Clanton (Walter Brennan) and the scowling faces of his sons. Clanton, the biggest land and cattle owner offers to Earps’ cattle, which Wyatt Earp politely refuses. Wyatt hears about the town Tombstone from Clanton and heads into town in the night with his two brothers for a shave, while leaving the younger one to guard the cattle. During his brief stay in the town, Wyatt kicks a drunken, gun-toting Native American before asking ‘What kinda town is this, selling liquor to Indians?’ It might be a line designed to extract few laughs, but you can understand hidden meaning of this question: what’s this Native American doing in the neighborhood of white Americans? Why can’t this guy get drunk and wave the gun at his own neighborhood? But, let’s not delve into the longest chapter of how old American movies spitefully dealt with ‘trouble-making’ Indians or Mexicans. Earp’s courage in taking down the drunken guy brings him the offer to replace the town marshal. He rejects the offer, but has a change of heart, when he returns to find his younger brother murdered and his cattle stolen. Wyatt accepts the position with one condition: his two brothers should be the deputies (in reality, Virgil Earp was Tombstone City Marshal and the only one, who held the legal authority when the mythologized shootout at O.K. Corral happened).

The early, small episode involving a Native American isn’t the only unflattering account of town’s minorities. There’s the brown-skinned, sensuous, bad girl Chihuahua (Linda Darnell). She is portrayed as ‘singer’ (which we can substitute with the word ‘prostitute’). She is in love with the charismatic white American Doc Holliday, for whom she is ready to sacrifice her life. Doc is the complex character after Wyatt, whose ribaldry as well as chivalry behavior bestows a fitting red herring for the tale. Doc seems to mirror the redeemable darkness that might afflict Wyatt’s conscience. When a polite, virginal girl with a positively infectious optimism arrives in Tombstone, looking for her former fiancee Doc Holliday, a new conflict arises. The expected tale of vengeance is pushed to the background and we get a more refined tale of burgeoning love. Wyatt falls head over heels in love with the girl named Clementine (Cathy Downs), who is insisted by Doc to immediately leave the town. The more surprising turn is that Wyatt is more interested in truly civilizing the place than seek for vigilante justice. He is not on the trail of Clantons to finish the unsettled business, but rather motivated to change the grey-shaded Doc. This fictional Wyatt Earp knows that winning over the tormented soul of Doc could really reinstate law in the Wild West town. The gradual build-up of a partnership between Earp and Holliday plays a vital role, when these men on one fateful morning, walked through the empty streets to confront their enemies once and for all.

Engel and Miller’s script is full of wise dialogues and memorable rebukes [“Mac, have you ever been in love” asks Wyatt, to which Mac replies, “No, I’ve been a bartender all my life”]. John Ford is a master at putting emphasis on the character’s psychological nature through the use of physical spaces and lightening (cinematography by Joseph MacDonald). The shadowy interiors reflect the emotional conflicts between the characters, whereas the narrative’s transitional moments unfurls in the serene, sun-bleached, spacious landscape. Two astoundingly staged sequences confirm “My Darling Clementine’s” classic status: Earp accompanies Clementine, shyly taking her arm to the square dance at the premise of partially built Church. He is clearly nervous on whether to ask her to join him on the dance floor. Then, the musician makes up an intro, ‘Make room for our new Marshall and his Lady Fair’. They both dance in perfect harmony, shaping romance and making up the cinema’s most heartfelt moment; Earp and his gang walk apart to the destined place for the shootout. The carefully choreographed sequence is full of uncertainty as swirling dust particles and unpredictable gun blasts scatter through the place. There are no unnecessary multiple-cuts. It’s just one long, perfect visual flourish. While there was ample tension visible between Wyatt and Clementine in the sequence leading to dance, the naturally tense shootout itself moves through like a balletic dance. This calm, flawless visual harmony attained by John Ford later influenced many revisionist western film-makers (Sam Peckinpah calls ‘Clementine’ as his favorite Western). Many of the best scenes in this film happen when Wyatt is at his most vulnerable situation than when he inflicts his authority with a six-shooter. Although Ford upholds the myth of Wyatt Earp, he and Fonda humanize the character enough to not turn him into a caricatured gun-toting frontier lawman.

Unlike many Westerns that recounted the legend of Wyatt Earp, John Ford’s “My Darling Clementine” (97 minutes) offers immense pleasures to viewers through rich details and profound visual renditions. What a thoroughly entertaining, ‘dad-blasted’ Western myth! (the insistence is on the word ‘myth’).