10 Noir Films That Are Under 90 Minutes: “Film noir” is usually used as an umbrella term to describe stylish Hollywood crime dramas of the 1940s and 1950s. Noir is described more as a style of filmmaking than a genre. Noir is like flora growing out of the wreckage of a fire—a sentiment caused by destabilizing societal conflicts. For the 40s, that was the post-war sentiment, which brought with it a new sense of fatalism, cynicism, and disillusionment within society, thus giving genre pictures like the gangster genre, the courtroom genre, or a simple crime film an added sense of pessimism.

Accurately, “noir” could be classified as a cycle or a phenomenon that repeats itself as a form of storytelling or visual emblem but has specific sets of aesthetic characteristics (low-key lighting, smoke) or stock characters (private detectives, boxers, femme fatales). If we look at film noirs, most clock in at an average of 90 minutes, with some touching the ceiling at over 2 hours. However, because noirs became the defining “genre” from the mid-40s to the late 50s, many independent studios began crafting B-movie noirs with shorter runtimes.

Most of these noirs were made so short because of the limited budget, but as this list will show, budgetary constraints didn’t hamper the impact of the storytelling in these movies. On the contrary, they were arguably more successful at times at delivering the “noir” ethos, with its own fatalistic and nasty bites.

Like most of this writer’s lists, none of these movies is notably ranked in terms of quality, but all of them should be watched. The one at the end, though, is what this writer truly believes is the perfect encapsulation of this list and is a must-watch. This list will be worked on in the future as well. Without further ado, let’s dive in.

1. The Hitch-Hiker (1953) | 71 mins

Based on a true story, The Hitch-Hiker follows two friends, Roy and Gilbert, whose fishing trip takes a terrifying turn when the hitchhiker they pick up is a sociopathic serial killer on the run. The movie becomes a tense affair as the two friends try to hatch a way out of their predicament while the serial killer uses them to escape, promising to kill them both once the ride is over. The all-male core cast was directed by the only woman to have directed a film noir, Ida Lupino. She crafts an independent B-movie noir with exciting subtextual ideas about masculinity.

At 71 minutes long, this is one of those short, white-knuckle, stripped-down noirs that delivers on its premise without throwing any new twists or turns. Instead of the traditional noir markers (dark alleyways, dimly lit rooms, nightclubs, flashbacks, and voiceovers), this film chooses desert vistas and open roads while also choosing to huddle inside the car, amplifying the claustrophobia as the two hapless travelers are held at gunpoint by this psychopath.

The premise is thin enough for the movie to become an efficient genre exercise in delivering suspense and existential dread. William Talman as the psychopathic hitch-hiker Emmett Myers, with one eye not closing, is suitably pulpy. However, because of its bare approach to filmmaking, it becomes a frightening and unsettling experience.

2. The Big Combo (1955) | 88 mins

Joseph H. Lewis will appear twice in this list and one of the more potent discoveries this writer made through this research on noirs. His films have a very bare-bones approach, but his filmmaking style evokes classical formalities, giving his movies an added sense of elegance. The film follows police Lt. Leonard Diamond, who is ordered to bring in the dreaded gangster Mr. Brown. Diamond takes a different tactic and goes after Brown’s girlfriend and his current obsession, which sparks a tussle between them.

If there is one movie that almost crystallizes how a noir film should look, it’s this one. And while Lewis doesn’t exactly change much of the established plotting within the genre itself, there is almost a painterly, poetic stillness in his direction even while recounting and documenting the film’s procedural and violent aspects. Part of that reason should also be credited to cinematographer John Alton, to the degree that this should feel more like Alton’s film.

The film is particularly helped by Richard Conte’s portrayal of Mr. Brown, who brings a slick coolness to the character while hiding a primal definition of evil. Lewis, particularly with the help of Alton’s expertise with the playing of chiaroscuro, brings a sense of panache to the intense sequences, which differ from usual noir offerings, giving a touch of incendiary yet artistic quality to the proceedings. And while the axiom of “the hero is only as good as the villain” is particularly skewed as the villain presides over the hero for most of the film, it only serves to make the ending more cathartic, with the final shot becoming one of the defining “noir” shots of history.

3. Gun Crazy (1950) | 87 mins

The second Lewis feature on the list, however, is more guerrilla than the previous entry but also one of the more pioneering ones. This film follows Bart Tate, an ex-army man whose long-held fascination with guns leads him to meet a kindred spirit in carnival sharpshooter Annie Starr. After upsetting the carnival owner, who lusts after Starr, they both get fired, which forces them to realize their fascination with guns through a crime spree. “Gun Crazy” introduces the “incendiary lovers on the run,” but what Lewis completely sells us on is that the volatility of such an enterprise requires a fiery performance and equally fiery chemistry.

Peggy Cummins as Annie Starr is almost hauntingly psychotic, while John Dall as Bart Tate sells the mania of the adult Bart as his fascination with guns morphs into attraction towards Annie. The scene where the two finally meet at the carnival is the definition of “sparks flying,” as they both realize that they have found their tribe. It would be a crime not to point out the technical prowess, especially the entire post-bank heist chase scene shot from inside the car.

The fascination with the gun is a sexual metaphor but also a form of post-war disillusionment, with the crime spree being the only possible method for these characters to fulfill their dreams and maintain their relationship. Lewis also touches on Tate’s conscience, defining his decision not to take a life throughout the film. Thus, when he finally takes a life, it adds a sense of melancholy to that tragic ending. The gamut of emotions the film touches and chooses to expand is impressive, especially in this short runtime.

4. The Killing (1956) | 85 mins

This meticulously crafted film follows Johnny Clay, a career criminal who recruits a five-person team consisting of men of diverse talents and motivations to hatch a daring racetrack robbery before going straight and getting married. However, unbeknownst to him, Clay’s girlfriend has plans of her own regarding the robbery. They say the third time’s the charm, and Kubrick’s filmography with his exactitude style comes to fruition in his third feature. While it doesn’t have the precise framing defining his aesthetic, the narrative is just eerily detailed, sometimes coldly so.

Under Kubrick’s hand, a routine heist story becomes a meticulous affair, with precise details given to the planning and recruiting of the affair. It is also bolstered by Sterling Hayden’s steely presence as Johnny Clay, one of the quintessential noir actors who carry cynicism and alacrity equally. The meticulous nature of the narrative itself engages the audience such that when the ending happens, with all of the inevitability of a noir, it becomes decidedly surprising and yet devastating, and somehow Kubrick manages to impress upon the unpredictability of the noir with that same exactitude.

It is perhaps not a surprise that “The Killing” stands out as one of the most influential movies of the heist genre, with the robbery and the masks being a defining feature across neo-noirs like Michael Mann’s Heat and Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight. But make no mistake, “The Killing” is a beast of its own.

5. Laura (1944) | 88 mins

A curious melodrama with all of the fatalism within the dreamlike nature of this cozy noir, “Laura” follows police detective Mark McPhearson, who is hired to investigate the titular character’s death. As the questioning of the suspects reveals a twisty plot, it also finds him falling in love with the murder victim. How quickly “Laura” shifts from a family melodrama to a hard-boiled noir to an achingly romantic affair is fascinating. For the first hour, Laura deals with the perception of the titular character through the three men in the film and the different reasons for giving into the allure of Laura’s character.

The second half is when the movie becomes a proper whodunnit, and the mystery is complicated but not convoluted (the typical hallmark of film noir), which helps maintain the viewer’s attention. While the movie manages to immerse itself in the limited mise-en-scene of the surroundings, it always seems to be a far slower cousin to its more famous noir counterparts. It’s more of a cozy murder mystery than a visceral and dark examination of the human condition until perhaps the very end.

Preminger manages to juggle themes of homosexuality as well as the psychological control men perceive they have over women, which shapes “Laura” into a fantastic indictment of the male gaze. The film’s supporting cast catapults it, especially Clifton Webb as Waldo Lydecker and Vincent Price as Shelby Carpenter. Webb’s portrayal is especially notable for depicting homosexuality within the constraints of queer coding.

6. Rope (1948) | 81 mins

The only color noir on this list, this Alfred Hitchcock-directed noir is also one of the more “experimental films” in the auteur’s oeuvre. It follows two men, Brandon (John Dall) and Philip (Farley Granger), who consider themselves intellectually superior to their friend David Kentley and decide to murder him. Strangling him with a rope and hiding the body inside an old chest in their shared New York apartment, they host a party and try to enjoy the macabre game as their guests come perilously close to discovering the crime, including their old schoolteacher, Rupert (James Stewart).

The innovativeness of the film stems from Hitchcok’s insistence on filming the movie as one long take, which he succeeds in doing by splicing in several 8-minute continuous shots (the length of film that would fit in a reel). It is not seamless, but it doesn’t feel that Hitchcock is losing control over his craft and his material. Rope is characterized by tension akin to a pressure cooker, with every reveal and turns in the narrative affecting like a gunshot. “Rope” also becomes the thesis statement for Hitchcock’s entire filmography, where the psychosexual motivations behind the premeditated murder chart the exploration in this movie.

How utter privilege and intellectual superiority could lead to dire actions at a whim, with the cynicism of the reasoning only heightening the eventual fatalism. The fact that the film is shot in color only serves to hammer home the visceral nature of the crime and the overall morbidity and catharsis of getting caught and getting closure. And lest we forget the clear queer relationship between the two protagonists, with Brandon being the one craving validation, which the entire party members manage to tiptoe through while Hitchcock navigates through those narrow avenues of queer code again.

7. Crime Wave (1953) | 73 mins

Andre De Toth’s first of the two noirs he directed in his career follows reformed parolee Steve Lacey, who is caught in a crime spree when a former wounded cellmate seeks shelter from him. His other two cellmates then try to pull him back to do one last job. All the while, a jaded and cynical police officer is doggedly pursuing the escaped convicts. This stripped-down, bare-bones “documentary-style” noir takes the usual treatment of an “ex-con brought back to a life of crime” and makes it pulse-pounding. The typical ploy of background music is avoided here, until the end of the film, in the climactic moment.

The violence is real and brutal, and thus the traditional characters and cynical attributes of noir are far more heightened even in this procedural tale. Shot in 13 days, there is a slow but steady rhythm within the narrative of “Crime Wave.” Toth sprinkles in the cynicism and darkness of the real world through conversations that, on paper, sound impressionably more fatal. But due to the lack of score, it just impacts significantly harder. In the second Sterling Hayden-led film on this list, the actor plays the jaded and crooked cop in fine form, but the chemistry of Gene Nelson and Phyllis Clark as Lacey and his wife is so believable that you buy into the narrative of the caper.

“Crime Wave” is also noticeable in how much it is shot on location and how beautifully Toth and the cinematographer Bert Glennon utilize light as well as darkness in noir. The climactic chase scene with downtown 1950s Los Angeles in all its glory is suitably striking. The antagonist of “Crime Wave” is the more existential one: how hard the stain of crime is to wash away and how the administration and inherent corruption fail the justice system.

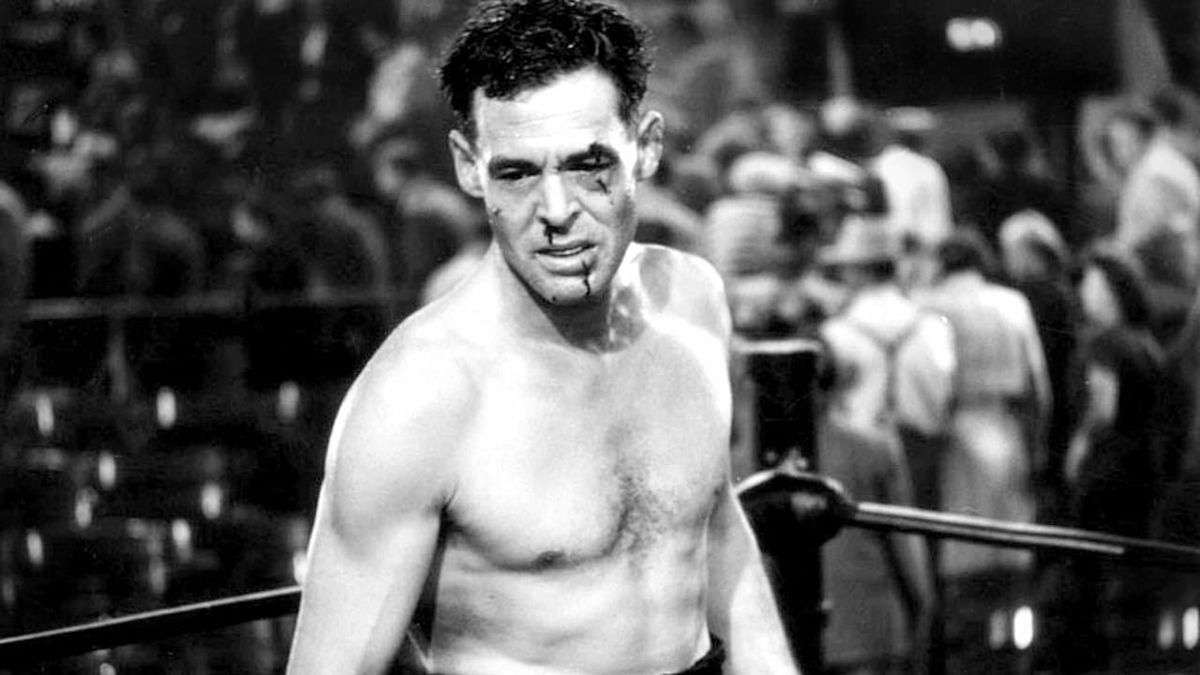

8. The Set-Up (1949) | 73 mins

Robert Wise’s melancholic noir follows a single night in the life of aging boxer Bill Thompson, steadfast in his belief he can still win, even as his wife Julie pleads for him not to get into the ring. Expecting a usual loss for Thompson, his manager takes bribes from the gangster without informing Thompson. Thus Thompson begins to fight for another win under his belt, unaware of his true fate if that happens. The ultimate victory for movies created during the golden age of Hollywood is when their core narrative becomes so ingrained into the DNA of storytelling that it becomes a near-perfect distillation of the entire plot into a trope.

The protagonist of the noir is the aging boxer, with boxing as a sport also being an American phenomenon, liable to be corrupted once gambling or earning money induces the sin of greed. It is also cinematic, and The Set-Up proves that from the opening sequence, where Robert Wise focuses on the feet of the participants as they jab, punch, and drop an uppercut through the jaw.

Through precise editing, Wise also shows the explicitness of violence and the implicitness of the aftermath affecting the spectators while simultaneously adding in the drama of the aging boxer and the long-suffering but still ardently believing wife. It all works in a tight, no-frills, no-filler 70-minute film without utilizing a flashback or a voiceover. But it never discounts the cynicism and failure of dreaming in a country five years removed from the war, where happiness could only be attained through relinquishing and accepting a last glory swing.

9. Pickup on South Street (1953) | 80 mins

Samuel Fuller’s electric and provocative noir-espionage drama follows pickpocket Skip McCoy, who unwittingly picks the purse of an unwitting mark containing a message destined for enemy agents. This leads to him becoming a target for a communist spy ring while the American police try to persuade McCoy to help them and join their side. What is striking about “Pickup on South Street” is the world-building and Fuller’s insistence on developing a lived-in network of criminals with their codes. But within those networks of thieves, prostitutes, and pimps, Fuller searches for humanity and finds it, extracting it from the deep burrows of machismo and quick-witted, razor-sharp dialogues – the trademark of American noir.

In the midst of it all, the politics of Sam Fuller are in full view here, as we see the ambivalence of our protagonist, Skip McCoy (Richard Widmark), towards working with anyone, irrespective of political affiliations. Fuller manages to craft the pure distillation of pragmatism in noir, evident since Fritz Lang’s “M,” where both sides of the law unite and join hands for a common cause.

Fuller also doesn’t shy away from showing bursts of emotional poignancy while maintaining his standard flourishes. He pulls the trick of following a character who enters their room, keeps their belongings down, and rests before finally acknowledging the intruder in their room, the camera panning to reveal the intruder. It’s a hallmark of fantastic technical direction while not forgetting to make the movie suspenseful and achingly romantic.

10. Detour (1945) | 66 mins

This zippy and short noir follows Al Roberts, a New York nightclub pianist who hitchhikes to Hollywood to meet his girlfriend, Sue. Taking a lift from a gambler, his life turns into a dreadful nightmare when the gambler dies. Therefore, he assumes the gambler’s identity, leading to terrifying events and harrowing prospects. This movie is the primary reason why this list was conceived in the first place. At 63 minutes long, excluding the credits, director Edgar G. Ulmer crafts one of the tightest screenplays a viewer could witness on screen.

The dialogues feel contrived to get the plot moving initially, but this has one of the best voiceover narrations conceived in the “film noir” template, this side of Humphrey Bogart’s “The Big Sleep.” This is also one of the absolute bleakest noirs ever crafted, with one of the nastiest femme fatales the genre has dished out. Vera, played by Ann Savage, is genuinely savage, more fatale than femme, and the key catalyst to the fatalism of the noir genre permeating through every cheaply made, sharply edited, expertly filmed B-movie noir.

The dialogues are laced with biting sarcasm, the Americana hopefulness slowly getting choked out. The narrative’s pacing inherently hastens the fatal ending of the protagonist Al’s (Tom Neal’s) life. He gets slaughtered by his circumstances to absolute tatters. It is a sight to behold like the darkest and bitterest coffee to be consumed and the purest distillation of the “noir phenomenon,” stripped down to its bare essentials and filtered to perfection.