“It insists upon itself,” said Peter Griffin about the Godfather in “Family Guy” when facing a sudden death situation with his family. These words of Seth MacFarlane have somehow managed to become a shitpost meme and the smartest critique of a movie at the same time. On the opposite end of this critique is “Piku” from Shoojit Sircar. The movie introduces itself as an unserious movie to such an extent that it almost becomes absurd. The premise of a constipated father going on a road trip with his daughter would bring anyone to a chuckle. The poster shows Deepika holding remedies to constipation and Irrfan holding a car and a commode chair (I wish it was called a stool stool) over his shoulders, all this while making funny faces.

Years after release, the movie is widely seen as a comfort movie and a warm hug. Strange compliments for a story that largely revolves around poop. “Piku,” as a movie, does not promise grand visuals or even grander narratives. It does not offer solutions, nor does it ask for explanations. “Piku” does the opposite of insisting, i.e., existing. It exists in a plane of time and space that is not only relatable but also comforting. It offers support and solace by showing the absurd struggles of a relationship. Moreover, it is a ‘simple’ movie. But as Tagore once said, “It is very simple to be happy, but it is very difficult to be simple.”

When we hear “world building,” we think of grand fantasies, but movies like “Piku” also require similar levels of expertise, understanding, and craft for creating worlds that are neither overtly stereotypical nor blatantly pandering. Here, I attempt to analyse the props and paintings of “Piku.”

The film opens with a morning shot of the CR Park signboard. The setting of the movie in CR Park is obviously a conscious choice. It is an upscale neighbourhood in South East Delhi and home to a large Bengali community. It was established on a rocky terrain in the early 1960s under the name EPDP Colony (East Pakistan Displaced Persons Colony) and later renamed after the deshbandhu (patriot) Chittaranjan Das in the 1980s. Thus, the very first frame of the movie not only establishes the relatively high standards of Piku’s family but also the pain of those who have left their lands behind. CR Park is not just a place; it is a delicate blend of bourgeois power and the grief of the displaced.

The first person to enter the movie is a local ironing man. He is not only a catalyst to introduce Piku’s busy character but also a symbol of class differences in society, a theme that is spread all around in the movie with the treatment of house help and Budhan. This class, caste, and commune loyalty is also seen when Rana doesn’t want to be seen as a driver and calls Piku in front or when Budhan has to sleep in the car and not a hotel, or when Piku’s family interrogates Rana Choudhary about his native land. It’s not a coincidence that Budhan doesn’t have a surname in the film.

Pretty accurate and, dare I say, somewhat stereotypical to show a Ray poster as the first wall art

Finally, we have our titular character on screen. Dressed almost like a nukkad naatak actress or a young revolutionary, Piku hasn’t boxed herself into the constrictions of ties and shirts. A strong figure walking right beside the frame of Rabindranath Tagore is enough to establish her position as the lady of the house. But again, isn’t it slightly stereotypical? “Hey, I am a strong Bengali girl, look, I even have a Tagore poster in my bedroom.”

Read More: 5 Bollywood women in a league of their own

Ramakrishna Paramahamsa was an Indian Hindu mystic. Although he was a devotee of the goddess Kali (a revered goddess in Bengali culture), he also adhered to religious practices from Hindu traditions of Vaishnavism, Tantric Shaktism, and Advaita Vedanta, as well as Christianity and Islam. Sarada Devi, addressed as the Holy Mother (Sri Sri Maa) by the followers of the Sri Ramakrishna monastic order, was the wife and spiritual consort of Ramakrishna Paramahamsa. She played an important role in the growth of the Ramakrishna Movement.

Later, we saw Bhaskor reading a book on Sarada Devi too. Further bolstering his narrative of “strong women”. However, she was also married, just like the other examples he gave.

On the right, we have “Indian Woman Playing Sitar,” an oil painting by Jagriti Sharma, establishing the art patron identity of the Banerji family, alongside politics and spirituality.

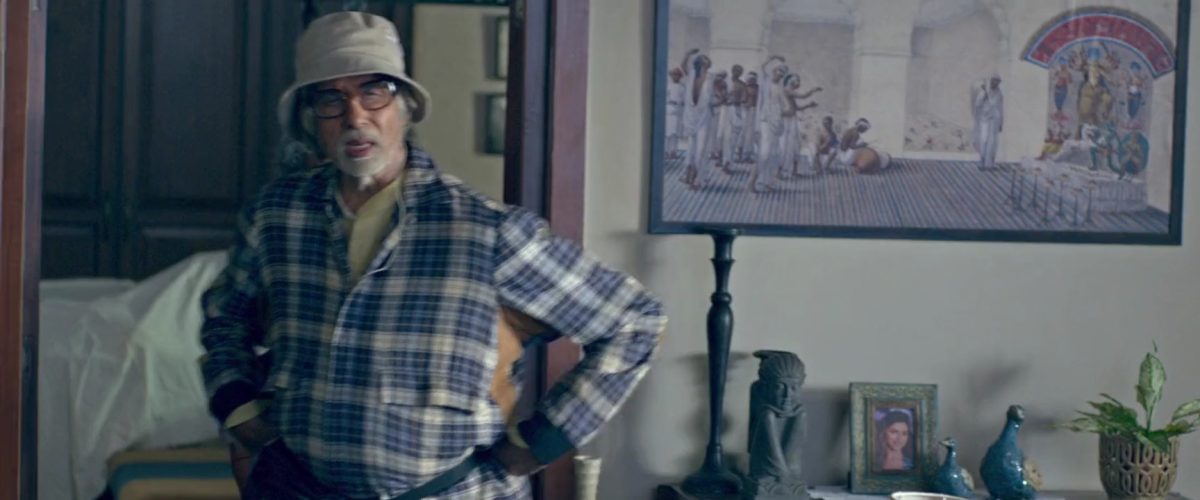

This watercolour painting by Sevak Ram (c.1770-c.1830) depicting a Durga Puja comes from the Patna school of painting, circa 1809. Durga is a form of the goddess Devi and is the most revered deity in the Bengal region. If there is one thing that truly moves the region of Bengal, it’s the Durga Pujo festival (a 9-day celebration for the goddess Durga’s victory over the demon Mahishasura).

Patna School of Painting (also Patna Qalaam, or Patna Kalam) is a style of Indian painting that existed in Bihar, India, in the 18th and 19th centuries. Patna Qalam was the world’s first independent school of painting, which dealt exclusively with the commoner and their lifestyle, which also helped Patna Qalam paintings gain in popularity. The principal centres of this style were Patna, Danapur, and Arrah.

While You’re Here: 10 Best Hindi Films of the Decade (2010s)

Name plates play an important role in the film. This one lacks individuality & bears the burden of age age-old patriarchal surname.

Jharna ghee is a type of fat staple in Bengali kitchens. From what I have heard, it’s found wherever there is a Bengali community.

Posters were also key in the set design for this film. Whether it’s Satyajit Ray in Piku’s home or these cars and the India Gate poster in Rana’s office, an obvious yet important shorthand for the business and “Delhiness” of Rana. Similarly, Piku’s office has a small “Keep Calm” poster symbolising the “modernity and newness” of corporate spaces.

Probably the most important picture in Piku’s home, there is little conversation about her mother in the film, but this frame says enough about their relationship

In Bhaskor’s room, we see one of the most renowned pictures of India, Swami Vivekananda in his iconic pose. Born in Calcutta, Swami Vivekananda (12 January 1863 – 4 July 1902) was an Indian Hindu monk, philosopher, author, religious teacher, and the chief disciple of the Indian mystic Ramakrishna. Vivekananda was a major figure in the introduction of Vedanta and Yoga to the Western world, and is credited with raising interfaith awareness and elevating Hinduism to the status of a major world religion.

Must Check: The 10 Best Hindi Films Of 2015

In this particular frame, a dejected yet strong Piku stands looking at her ill father. Maybe this was the time she realised how little time they both have with and away from each other. In that moment, she probably wants to cry in regret, but also wouldn’t mind scolding her father. She stands at the crossroads where she is strong enough to take care of her father but not strong enough to deal with his little quirks, she is smart enough to tell good from bad but not smart enough to take time for herself. In that moment, Vivekanand looks at her and probably thinks of places she can go.

In their room in Banaras, we see a mural of Shiva in his dancing stance. Generally, Shiva is seen in a calm meditative pose, but here the chaos & beauty of Tandav fits perfectly with Banaras and their lives

Probably the most important prop of the movie, it summarises the absurdity and necessity perfectly. You want to leave it, but you can’t live without it. And this reminds me of the concept of MacGuffin popularized by Hitchcock. It’s defined as “In fiction, a MacGuffin is an object, device, or event that is necessary to the plot and the motivation of the characters, but insignificant, unimportant, or irrelevant in itself.”

And I would like to propose an unusual MacGuffin in “Piku,” i.e., poop (or lack thereof). While it is critical for the plot and the motivation of the characters, it’s somewhat irrelevant in itself. Any other disease in place of constipation would have brought a higher level of urgency or suspense in the audience, but constipation brings out the absurdity, the lack of seriousness, and the comedic value. Maybe, at the end, filmmaking is a balancing act of absurdity and reality.

Some other important props of the film include A knife, bangles, a hearing aid, boti, jalebi, and a cycle (also love the fact that Kayam Churna is a sponsor of this film)

Compared to the B. Banerji nameplate in Delhi, Champakunj (literally, a grove of Champa flowers) is much more intimate, nostalgic, and poetic. Makes sense when Rana says we shouldn’t forget our ‘roots’.

I think this frame defines Champakunj and the conflict of selling it. While the CR Park bungalow is filled to the brim with Bengal emblems, it can’t substitute the familiarity of Champakunj. Champakunj is not just the roots of Piku, it’s also the stem on which Bhaskor once leaned on and it’s also the canopy that invites a stranger like Rana inside. When Rana looks at vintage pictures of the Banerji family, he doesn’t see Bengal through its stalwarts; he sees Bengal through its common man and woman.

He sees the past of the Banerji family and starts understanding the present. Looking after the old runs in the family, be it Bhaskor fighting for Champakunj or Piku sacrificing herself for Bhaskor. They can’t help it; they can’t help being romantic, and they can’t help being tough to understand and tougher to love. They can’t help being a strange blend of medicine box and flowers, of Kolkata and Delhi, of doodh and cola, and of art and atrocities. Maybe that’s the essence of Bengal, strong and sweet simultaneously.

Pandora’s Box closes.