Institutional or structural racism manifests itself in a variety of ways. On the surface, it’s difficult to see how urban planning could be linked to racism. If urban planning could be reduced to its funding, design, or construction, then we are missing out on the pivotal social impacts. Questions about the demarcation of urban spaces are frequently raised in a country like America, where cities are still reeling from the after-effects of racial segregation. In fact, understanding how urban planning was used as a complex tool to create and sustain social inequalities between communities of white Americans and people of color is central to understanding the history of modern America. Racist Trees (2022), a powerful documentary by Sara Newens and Mina T. Son, shows how something as simple as a tree cover played a critical role in segregation policy.

Palm Springs, California carries the image of a progressive, liberal desert paradise. Since the 1930s, the resort city has been a favorite of American celebrities. Tourist brochures promote it as an oasis of relaxation and rejuvenation. However, for the black-majority residents of Palm Springs’ Crossley Tract neighborhood, a row of tamarisk trees stands tall in their backyard as a symbol of institutional racism. Sara and Mina’s Racist Trees illuminate the dark chapters of Palm Springs’s history in five concise chapters. They show how systemic racism is as tenacious as those tamarisk trees.

Racist Trees tells the story of how a working-class African-American neighborhood arose amid the white tourist paradise. The Crossley Tract, also known as the Lawrence Crossley neighborhood, was named after its developer, who also happened to be Palm Springs’ first black resident. Mr. Crossley was a respected entrepreneur. But the discriminatory housing restrictions of the time allowed him to purchase land outside of the city. Crossley purchased his land in 1956 and developed it as an African-American neighborhood. When he and his wife moved to the tract in 1958, they became the tract’s first residents.

In the same year, Westview Development began its work on a golf course on undeveloped county land, adjacent to Crossley Tract. Later known as, Tahquitz Creek Golf Course, it was purchased by the city in 1959 and is still owned by the city. Crossley Tract was annexed to Palm Springs by the 1960s. The exact date that a large grove of invasive and poorly maintained tamarisk trees was planted on the border between the golf course and Crossley Tract sparks a debate in Racist Trees. But there’s no denying that the trees denied long-time residents of a historically African-American neighborhood a breathtaking view of the San Jacinto Mountains.

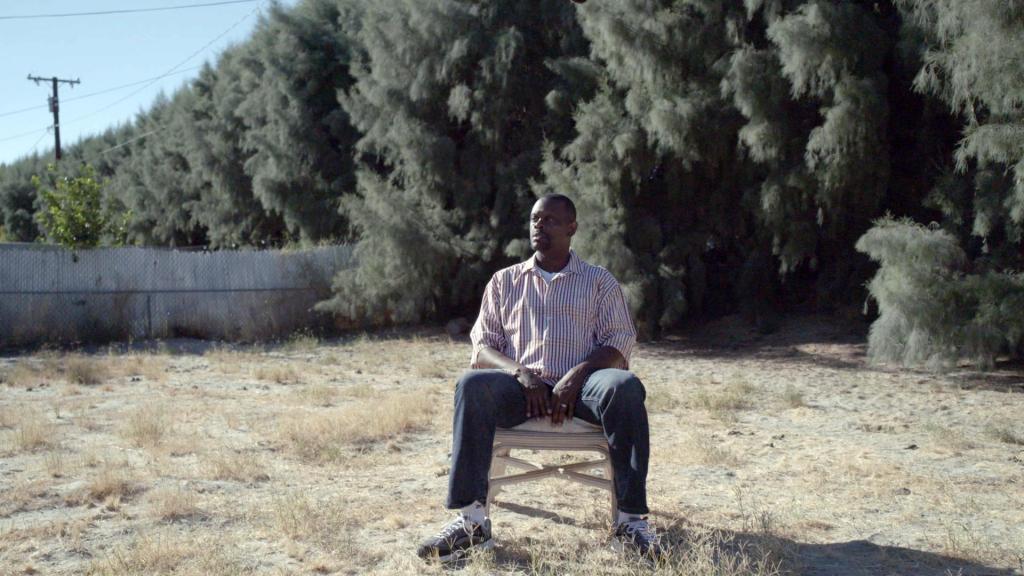

The trees are purely aesthetic for the residents of the predominantly white gated neighborhood opposite Crossley Tract. Of course, there are fears that removing the trees and chain link fence will cause ‘dogs and children from Crossley Tract’ to run onto the golf course. Requests to acknowledge the racial agenda behind the tree plantation, as well as removal requests, were repeatedly denied by city officials. Nonetheless, the community found a white spokesperson named Trae Daniel, a real estate agent who lives in Crossley Tract.

In Racist Trees, Sara and Mina explore the different viewpoints behind Trae’s involvement in the campaign for tree removal. The documentary maintains some skepticism about Trae’s alleged opportunistic behavior. However, Trae makes an excellent point about how institutional racism is inextricably linked to the wealth disparity between black and white neighborhoods. A house in Crossley Tract is worth less than a house of similar proportions in the adjacent white neighborhoods. Racial discrimination in the housing market is not a new phenomenon. Racist Trees go on to explain how discrimination prevents certain communities from amassing or creating generational wealth.

Do city officials start listening to Crossley Tract residents because Trae is white? Is it because he speaks the profit and money language? Whatever it is, when Desert Sun journalist Corinne S Kennedy wrote a detailed story about the Crossley Tract, the row of Tamarisk trees made national news. Many vituperative trolls were also drawn to the article. Of course, city officials may not come out and defend their predecessors’ decisions. They did agree, however, that the trees were a ‘nuisance’ and a potential fire hazard. A certified arborist explains why tamarisk trees have a high water consumption rate. Furthermore, we learn why the trees were originally planted as a perfect windbreaker in the parched land of sandstorms.

Is there a racist agenda behind this particular row of tamarisk trees? Racist Trees delves deep into Palm Springs’ archived history to provide an affirmative answer. Or, at the very least, Racist Trees covers enough material to refute the bold claim that Palm Springs was not plagued by the malaise of institutional racism. The Palm Springs city limits include a portion of the Agua Caliente Indian Reservation. Indigenous lands were legally taken away by federal policies. Section 14 – now known as downtown Palm Springs – piqued the interest of developers in 1959 because it was adjacent to the expanding shopping and entertainment district. Originally, it was a neighborhood for the city’s low-income non-white, blue-collar workers.

The conflict over Agua Caliente lands began with the Indian Leasing Act of 1959, which allowed certain tribes to lease their lands for up to 99 years. A state-sanctioned crackdown ensued, resulting in the brutal and forceful eviction of Section 14 residents. Racist Trees’ chronicle of Section 14 history reveals how systemic racism has always been the norm in Palm Springs urban planning. In fact, many of the original Crossley Tract residents were the black people evicted from Section 14.

The row of tamarisk trees that stood tall as a reminder of racist practices has vanished. The end credits of Racist Trees inform a relief from the artificially depressed property values for Crossley Tract residents. At the same time, Sara Newens and Mina Son’s documentary leaves us thinking about the racial and social injustice that’s deeply embedded in the blueprints of our cities and towns. In that vein, Racist Trees (88 minutes) provides an excellent window into the structural racism that people face in their daily lives.

![Repast [1951] Review – A Wonderfully Subtle Marital Strife Drama](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Repast-1951-768x432.jpg)

![Demon [2016]: A chilling Jewish folklore haunting Poland long after the War](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Demon-2015-768x327.jpg)

![Take Back the Night [2022] Review: An effective #Metoo thriller with an infuriating monster](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Take-Back-the-Night-1-768x405.jpg)

![Vampires [1998] Review: Style. Swag. Savagery.](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/vampires-cover-1-768x432.jpg)