In Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s latest film “Evil Does Not Exist,” the seemingly peaceful coexistence between humanity and nature becomes a haunting meditation on environmental stewardship and generational consequences. Set in the small village of Mizubiki, home to roughly 6,000 inhabitants, the film opens with deceptive tranquillity and slowly unfolds into a devastating critique of urban encroachment on rural spaces.

The story centers on Takumi, a taciturn woodcutter, and widower. He lives with his young daughter Hana, who embodies the delicate balance between human life and the natural world. Their daily routines – studying local flora, identifying tree species, and respectfully harvesting what the forest provides – represent a sustainable way of life that’s increasingly under threat. Hamaguchi captures these moments with crystalline precision, allowing his camera to linger on the methodical rhythm of Takumi’s axe work or the careful steps of Hana as she navigates familiar forest paths. This pastoral existence is shattered when a Tokyo-based company announces plans to construct a glamping resort in their area. The arrival of two corporate representatives, Takahashi and Mayuzumi, sets in motion a chain of events that expose the fundamental disconnect between urban development and environmental preservation.

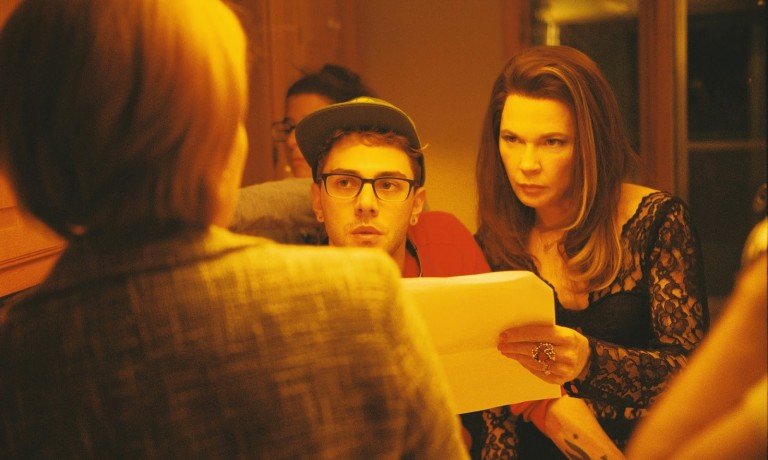

In a scene of breathtaking tension that forms the beating heart of “Evil Does Not Exist,” director Ryûsuke Hamaguchi proves that the most riveting drama can emerge from something as seemingly mundane as a community meeting. Here, in a room that could be anywhere in rural Japan, we witness the collision of two worlds with the precision of a master watchmaker.

The sequence unfolds like a perfectly orchestrated chamber piece. A restaurateur, played with quiet dignity by Hazuki Kikuchi, speaks of her udon noodles and the spring water that gives them life. It’s not just about noodles – it’s about tradition, about a way of life that can’t be relocated or replicated. In her soft-spoken testimony, we hear echoes of every small business owner who has ever faced down the machinery of progress. Then there’s the young hothead (Yûto Torii, crackling with contained fury) who says what everyone’s thinking but fears to voice.

His anger isn’t the manufactured rage of Hollywood confrontations, but the genuine frustration of watching one’s homeland being carved up by spreadsheet decisions. But the scene’s true masterstroke comes from veteran actor Taijirô Tamura as the village elder. “What you do upstream will end up affecting those living downstream” isn’t just an environmental statement, it’s a perfect metaphor for how the choices of the powerful ripple through society. Delivered with the quiet authority of someone who has watched rivers flow for decades, it’s the kind of line that makes you want to stand up and applaud for its simple truth.

What makes this scene so magnificent is how Hamaguchi lets it breathe. The camera doesn’t dance around nervously or cut away for dramatic effect. It sits with the discomfort, lets us watch faces react, and allows silence to do its work. This is cinema that trusts its audience to lean in rather than sit back. Modern Hollywood could learn a thing or two from such patient, confident filmmaking.

What makes “Evil Does Not Exist” particularly potent is how it subverts expectations about environmental conflict narratives. Rather than presenting a simple David-versus-Goliath tale, Hamaguchi weaves a more complex tapestry about the price of ignorance and the consequences of disrupting natural orders. The film suggests that even well-intentioned outsiders like Takahashi, who becomes enchanted with the village’s way of life, can inadvertently become catalysts for destruction.

The film’s visual language is deliberately unadorned yet deeply affecting. Hamaguchi and his cinematographer capture the changing seasons of Mizubiki with documentary-like attention to detail, making the landscape itself a central character. The pristine streams, frost-covered trails, and dense forests aren’t just backdrops but living entities that demand respect and understanding.

Also Read: Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Evil Does Not Exist (2023) Movie Ending Explained & Themes Analyzed: What Happens to Hana and Takahashi at the End?

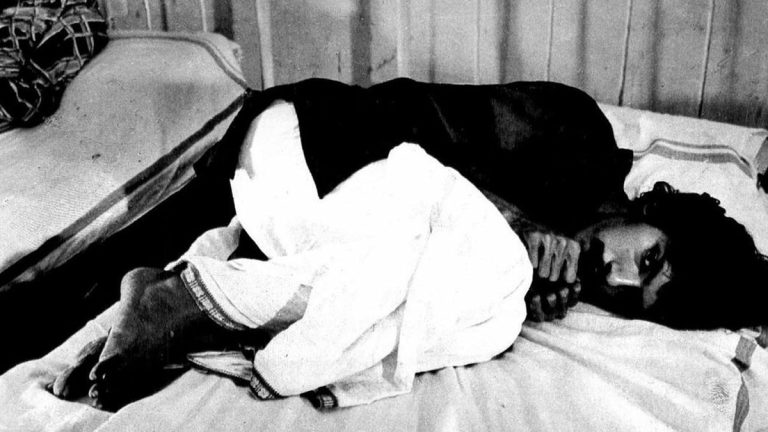

As the narrative progresses, the film takes an unexpected turn toward darkness. The climax, featuring two devastating deaths, serves as a stark reminder that nature operates beyond human concepts of morality or justice. One death comes by human hand, while the other arrives as an inevitable consequence – a brutal illustration of how actions ripple through generations. This sequence transforms what began as a gentle environmental parable into something far more primal and disturbing.

Hitoshi Omika’s debut performance as Takumi is remarkable in its restraint. His character’s evolution from a quiet woodcutter to someone forced to make impossible choices carries the weight of generations of environmental stewardship. Young Ryô Nishikawa as Hana represents both hope and vulnerability – a child at home in nature who nonetheless faces an uncertain future shaped by present-day decisions.

The film’s title becomes increasingly ironic as the story unfolds. While evil may not exist in nature’s arbitrary patterns of destruction and renewal, human actions introduce moral complexity into this neutral system. The glamping project, presented with corporate optimism, represents a form of evil born from ignorance rather than malice. The kind that believes nature can be packaged and sold without consequences.

Eiko Ishibashi’s score deserves special mention for its role in building tension. The music shifts from pastoral serenity to discordant warning signs, often cutting off abruptly to leave scenes in pregnant silence. This audio strategy mirrors the film’s larger themes about the disruption of natural harmonies.

“Evil Does Not Exist” marks a significant departure from Hamaguchi’s previous works like “Drive My Car” and “Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy.” While those films explored human relationships through dialogue and urban settings, this new work speaks through silences and natural spaces. Yet it maintains his characteristic attention to human behavior and the small moments that precipitate large changes.

The film’s conclusion might leave viewers with uncomfortable questions about the price of progress and the true meaning of stewardship. It suggests that our relationship with nature isn’t about dominion or even preservation, but about understanding our place within a system that will ultimately outlast us. The tragedy lies not in nature’s indifference to human life, but in our inability to recognize how our actions against nature become actions against ourselves and our descendants.

In an era of increasing environmental crisis, “Evil Does Not Exist” offers no easy answers or comfortable reassurances. Instead, it presents a stark reminder that nature’s balance, once disturbed, seeks restoration through means beyond human control. It’s a film that lingers in the mind long after viewing, asking us to consider not just our immediate impact on the environment, but the legacy we leave for future generations who must inhabit the world we shape today.