A Trifecta of 20th-Century Classics: The world-renowned character of the ‘Little Tramp,’ played by Charlie Chaplin, said in the movie Modern Times (1936), “Life can be wonderful if you’re not afraid of it. All it takes is courage, imagination … and a little dough.” This dialogue sums up the philosophy of life, but the reality is that earning that ‘little dough’ is the most challenging part.

Three films released in three different decades of the 20th century reveal the degree to which inequality prevails in society. Socio-economic differences, political power play, and urbanization cut across the lives of the ‘have-nots’ and make their survival trajectory full of atrocities and struggles. Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948), and Bimal Roy’s Do Bheega Zamin (1953) have left a lasting impact on the literature of cinema as far as understanding the societal structures are concerned.

All three movies talk about the tussle between the haves and the have-nots. They highlight the impact of the Industrial Revolution, the rise of capitalism, and the colonial systems of feudalism, which undercut the idea of true modernization and reveal the inert inequalities prevailing in society. The narratives stand the test of time and prove to be quite relevant even in today’s day and age. Set in different social contexts and time periods, they all succeed in mirroring society and showcasing the trials and tribulations of its people from the lower rungs.

In an article in The Chronicle, Ciara White notes that “Modern Times does not shy away from showing the horrors of American life at the time. Despite its comedic nature, the movie has a tragic core.” Charlie Chaplin uses the template of humor to unearth some of the most pathetic and dark sides of the ‘so-called’ developing society. Unfortunately, numerous people rushing to the cities to find better opportunities and better lifestyles end up toiling even for two square meals. This is precisely what Modern Times succeeds in showcasing. A certain kind of madness engulfs the workers in the city, leading almost to anxiety and isolation. Rapid mechanization erodes all human emotions, and money becomes the only goal.

One of the most intriguing scenes in the movie is when the little tramp is working on a conveyor belt of a factory machine, and his hands almost start moving like a machine to fix the bolts. This robotic movement, coupled with the increasing speed of the belt, reaches a point where the tramp loses consciousness and falls to the ground. This scene, despite its overtly comedic staging, invokes pain and empathy in the viewer and raises some critical questions about where this ‘manufactured development’ leads us. The stark gap between the sensibilities and circumstances of the Bourgeoisie and Proletariat becomes evident through the narrative.

Similarly, Bicycle Thieves also talks about the pathos of people experiencing poverty. Vittorio De Sica was one of the pioneers of the Italian Neorealist cinema, which attempted to break away from the template of filmmaking that only focused on the lavish lifestyle of the rich. These films held a mirror to society and showcased the economic struggles of the oppressed class. Often filmed in real locations with non-actors, neorealist films carved a cutting-edge style of realism. Bicycle Thieves is about a man who maneuvers through the harshness of the city to earn money and support his life and family.

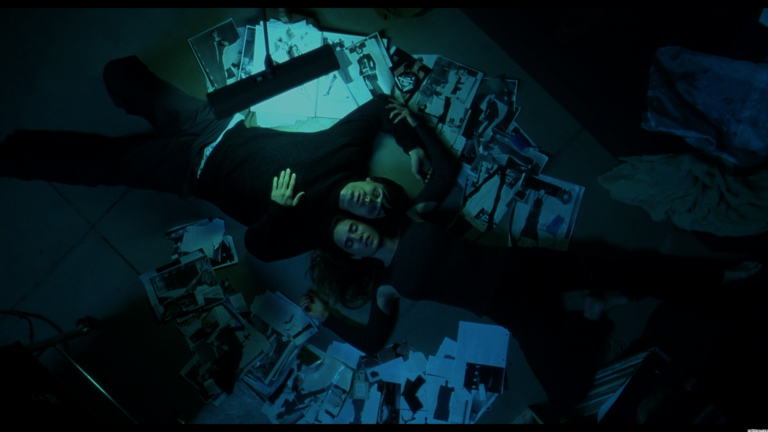

Bosley Crowther in THE SCREEN; Vittorio De Sica’s ‘The Bicycle Thief,’ a Drama of Post-War Rome, Arrives at World asserts, “Bicycle Thieves is a political parable and a spiritual fable, at once a hard look at the conditions of the Roman working class after World War II and an inquiry into the state of an individual soul.” One scene in the movie that sums up the narrative is when the protagonist and his son are seen struggling on the roads of the scorching city to find their bicycle, enter a canteen, and are compelled to eat dry slices of bread; the trauma and the agony are apparent in their eyes.

On the other hand, Bimal Roy takes on the theme of feudalism in the agrarian society of India. Roy went on to make Do Bheega Zameen after getting heavily inspired by Sica’s Bicycle Thieves. Contextualizing the movie’s concept in the Indian milieu, Roy brings to screen the exploitation and lack of protection of the farmers in the newly independent country. From the socio-political lens, national integrity was the country’s primary goal. However, such notions were still broken and required a lot of repairs. Bimal Roy, one of the stalwarts of the parallel cinema movement in India, was sure to meddle with the questions of humanity at the cross sections of livelihood, survival, urbanization, national identity, and economic inequality.

“Bimal Roy is equally candid in his representation of the brutality of city life, of the callousness, anonymity, and instrumentality that appear to mark most human relationships in the urban setting,” notes Vinay Lal in an article published by the UCLA Social Sciences archives.

In one scene, a woman takes a rickshaw to flee, and a man hops on the rickshaw of the protagonist, Shambhu Maheto, and asks him to follow the woman. His pain of pulling the rickshaw in the city’s scorching heat is revealed through his face and the nerves of his legs. The passenger constantly pushes Shambhu to move faster. Gradually, the speed reaches a point where Shambhu is at the pinnacle of his physical energy. One of the tires is dismantled, and Shambu sustains severe injuries. This scene depicts the compulsion to earn money beyond the threshold of human capacity. It takes one back to the factory scene of Modern Times.

Describing the scene further, Sameera K. Rehmani, in the article ‘Do Bigha Zamin’ (1953) — A View of Post-Independence India through the Lens of Italian Neorealism, says, “In less than sixty seconds, Roy succinctly encapsulates Shambhu’s desperation, a desperation which compels him to risk his life for a meager amount of money.”

The pain and compulsions remain the same regardless of geography and social context. The kind of mental and physiological trauma becomes a part of existence, beautifully reflected in these films. Alluding to the concept of the Banality of Evil by German philosopher Hannah Arendt fits best into this argument. The normalization of barbarity, cruelty, and the nature of the deep-seated socio-economic inequalities creates a greater concern arising out of the narratives.

All three movies, Modern Times, Bicycle Thieves, and Do Bheega Zamin, have been highly acclaimed and instrumental in initiating conversations around flawed societal structures. These cinematic classics continue to resonate, underscoring that while life may indeed hold wonders, the price of those wonders is often paid by the laboring hands of those at the bottom rung, and the pursuit of that elusive “little dough” remains an enduring challenge in the human journey for survival.