One of the most fundamental parts of writing a memorable, likable character is the idea of pathos. Pathos is the appeal to the emotions of the audience, and in film, this is often done through a character’s actions, dialogue, or back-story. Appealing to emotions is not easy, but when done right you will be left with complex, memorable characters like Michael Corleone (The Godfather, 1972) or Forrest Gump (Forrest Gump, 1994). We often empathize with the struggles of these characters, and sometimes can even see parts of ourselves in them. However, when done poorly, characters can come off as insincere, unrealistic, or unrelatable. Nowhere in the world of film is this more prevalent than films about drug addiction.

Addiction is not easy to empathize with; it’s an inherently personal and painful challenge, and unless you have gone through it or know someone who has, it can be tough to relate to. Those who write films about addiction know this, and don’t want to risk viewers being unable to relate or empathize with their characters. For this reason, they often go too far in the other direction, and write their characters as so sympathetic and safe that they come off as sappy or unrealistic. Examples of this are not rare, either.

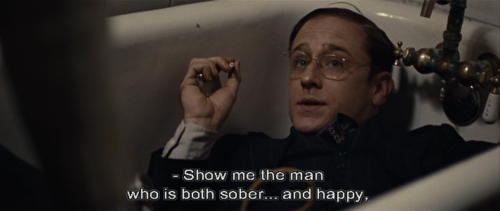

Sandra Bullock’s Gwen Cummings in 28 Days suffers from rampant alcoholism, but it’s seen more as an endearing character trait to be overcome rather than the serious, crippling addiction it is for millions of people worldwide. In Clean and Sober, a tearful Michael Keaton is absolved of his drug addiction only after cleanly coming to terms with what caused his drug addiction in the first place. A majority of films about addiction follow an almost identical path – addiction, rehab, recovery – and almost all fail critically and commercially. This might be because addiction is rarely this simple, and downplaying the struggles of those suffering with drug addiction makes for an unrelatable and un-enjoyable experience. To make a successful film about drug addiction, it only has to be one thing: real.

Making a good film about addiction is far from impossible, but it is remarkably difficult. Making the viewer empathize, rather than sympathize, with the characters on screen experiencing the horrors of addiction is not easy. Writers, actors, and directors all have to straddle the line of making their film come off as realistic while not appearing to be overly endearing, insincere, or campy, which is difficult with a violently traumatic topic like addiction. While rare, there are some fantastic examples in film of where this line was traversed with perfection.

Rachel Getting Married depicts a deeply-flawed Kym Buchman (Anne Hathaway) struggling continuously with her addiction and the death of her younger brother for which she was responsible. Kym’s flaws prevent her from successfully reconciling with her family before her sister’s wedding, and the film ends with many relationships still broken and Kym returning to rehab. The now-legendary Requiem for a Dream depicts four individuals all struggling with heroin or diet pill addiction, all of which end in equally horrifying and painful ways. Here, there are no happy endings; instead we’re left with much more nebulous, open-ended possibilities, which reflects addiction a little more accurately.

Addiction is rarely something that is cleanly tied-up with a happy ending. Instead, addiction is a struggle that can last years, even after someone’s sober. This is not to say that someone with addiction can’t have their own happy ending, but odds are it’s nothing like what we see in movies about substance abuse. Addiction is not funny or endearing, nor is it a campy, over-the-top struggle designed to make us feel as sympathetic towards someone as possible. Addiction is real, much like the characters that experience it. It’s not something that can be wrapped up with no strings attached. In films that depict addiction realistically, it’s clear that this idea is understood.

Related: I Need You Dead (2021) Review

Many films in this category use addiction as a story, rather than using addiction to help tell a story. When we use addiction as a story itself and make sympathetic characters rather than empathetic ones, we diminish the real struggles of addiction. When done correctly, we can show what addiction really is: an extremely personal and difficult struggle, but not an impossible one