The subgenre of biopics focused on notable musicians has become so popular that its trappings have become as familiar as those of a superhero film. Even though many of these artists had wildly different trajectories and experienced various career fluctuations, those nuances tend to be sanded off in a Hollywood film that must adhere to a typical three-act structure with a “rise and fall” narrative. Given that Bruce Springsteen has been covered in countless documentaries, it makes sense that the first narrative film about his life makes no attempts to encapsulate the entirety of his career.

“Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere” (2025) is centered on the making of Springsteen’s most famous album, but its narrow area of focus isn’t just because of the famous songs. Rather, writer/director Scott Cooper takes an intimate look at a troubling period within the life of “The Boss” in which his mental health took a turn for the worse.

Even if culture has steadily grown more open in its discussion of depression and hopelessness, the notion that Springsteen was able to craft his defining masterpiece during this challenging period is both staggering and perplexing. Although “Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere” offers many insights into how “Nebraska” was seen as a groundbreaking detour from the artistic norm, its greatest power is reckoning with Springsteen as an individual.

“Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere” begins after Springsteen, played by Jeremy Allen White, has already earned widespread recognition for “The River” and has gone through a series of successful tours alongside his loyal manager Jon Landau (Jeremy Strong).

Although the executives at Columbia are keen to take advantage of this trajectory with another crowd-pleasing album, Springsteen is haunted by memories of his father, Douglas (Stephen Graham), with whom he has never resolved his issues. Burnt out by the strain of traveling the country, Springsteen returns to his hometown in New Jersey to craft a personal, intimate collection of songs that seem to have no commercial prospects.

Cooper has become a low-key master of the grizzled, decent aura of America’s heartland, as he’s turned his focus to troubled figures of masculinity in films like “Out of the Furnace,” “Hostiles,” and “Black Mass.” “Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere” is the most stylistically similar to his debut feature, “Crazy Heart,” in which Jeff Bridges played a fictionalized musician loosely inspired by Kris Kristofferson and Hank Thompson.

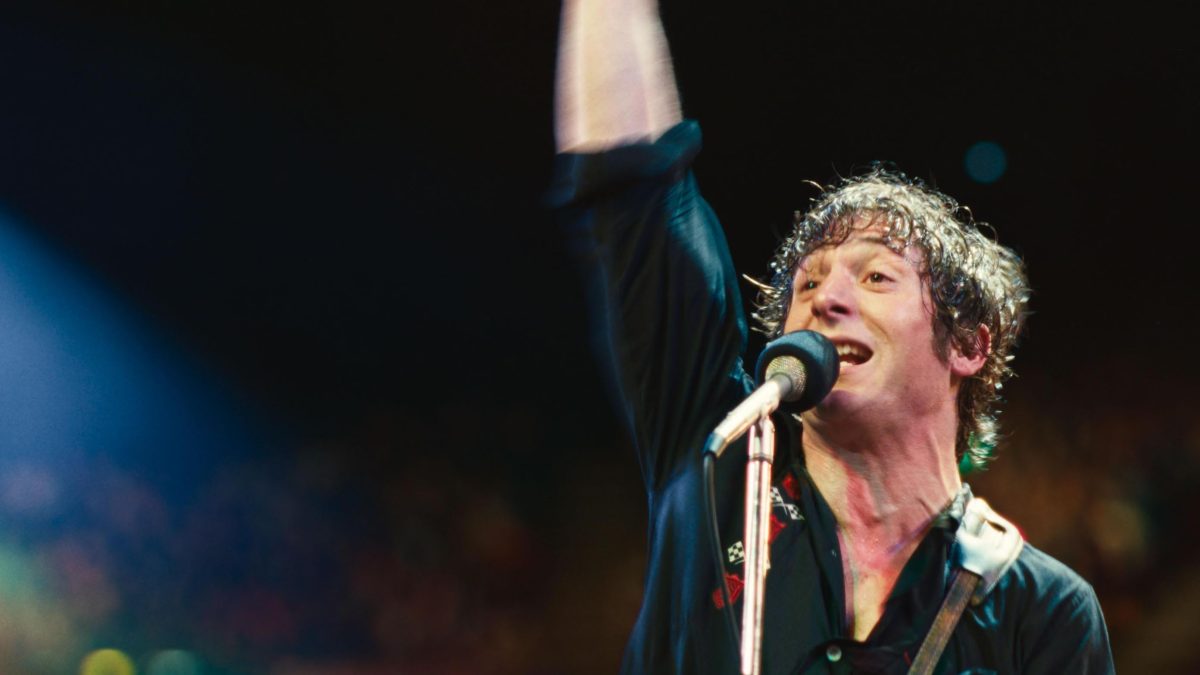

“Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere” could have easily felt boxed in by the facts of its subject’s life. But the stark difference between Springsteen’s rapturous public appearances and moments of personal anguish makes use of viewers’ existing knowledge. “Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere” doesn’t make the argument that “the real Bruce” was completely unknown to his fans. Rather, it suggests that the personal, painful stories within “Nebraska” were even more self-expressive than Springsteen’s followers may have even understood.

Even though “Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere” tells a timeless story about a troubled artist trying to work through his demons, any film about such a notable figure requires a performance that encapsulates the essence of its subject. It won’t be surprising to fans of “The Bear” that Jeremy Allen White delivers a soft, soulful performance as a highly dedicated creative genius, but what’s most unexpected is the vulnerability within the film’s interpretation of Springsteen’s motivations.

White is entirely believable as a rising star, both content with his work and terrified of being lost within his darker thoughts. Although he’s rarely aggressive, White provides an understanding of why Springsteen was determined to resolve his traumas with an unorthodox record, even if it meant jeopardizing his career.

The sparsity of fully-fledged musical numbers makes the step-by-step recording process an exhilarating one, as “Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere” does not spare details in showing why “Nebraska” was written off by some of Springsteen’s biggest advocates. This is in part due to an equally moving performance by Strong, who depicts Landau as a friend, mentor, and frequent therapist to Springsteen. It’s a nuanced relationship built on mutual trust, and the film’s refusal to add artificial drama makes the collaborative nature of their partnership more intriguing.

Landau’s arc isn’t just one of allowing Springsteen to both earn the help he needs and maintain his grasp on America’s blue-collar listeners, but to recognize what exactly he has the power to do. Being there for a friend is a challenge in its own right, but Landau faces more difficulty in leaving Springsteen to heal himself at his own pace.

The flashbacks to Springsteen’s father and mother (Gaby Hoffman), shot in crisp black-and-white, are initially a bit awkward, but eventually tie in nicely to the narrative once it becomes clear why specific memories are relevant to Springsteen’s creative process. The film is also quite tender in its exploration of Faye Romano (Odessa Young), a composite character created to represent different love interests within Springsteen’s early years. While her appearance during any moments needing an emotional boost can at times feel a bit convenient, Faye’s character arc is surprisingly detailed, and resolves itself in a manner that is both ambiguous and emotionally realistic.

Perhaps it was necessary to examine the business politics involved in the inception of “Nebraska,” but the film’s weakest segments involve figures like Columbia head Al Teller (David Krumholtz) and mixing engineer Chuck Plotkin (Marc Maron). Neither performance is bad, but the pressure mounting on Springsteen to release a hit album is only interesting when it offers an avenue for more heart-to-heart conversations with Landau.

Other supporting characters like recording engineer Mike Batlan (Paul Walter Hauser) and guitarist Steven Van Zandt (Johnny Cannizzaro) may feel a bit underserved, which could be perceived as a disappointment for Springsteen aficionados, but they fulfill their purpose for a film with as specific a focus as “Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere.” Hauser, in particular, gets some laughs, which are earned given how involved the drama can get as the film reaches its conclusion.

“Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere” exists to tell a story, and not to take advantage of a legacy, but that attribute may be why it succeeds where too many other biopics fail. In exposing an empowering story about how art can heal the deepest of wounds, “Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere” has an intimate understanding of why “The Boss” still resonates with people, but also explains his appeal to novices and non-fans. It’s unabashedly earnest, poetic, and at times honest to a point of uncomfortability; the same could be said about “Nebraska.”

![Battle: Freestyle [2022] Review – Confused and Problematic Film that Disappoints](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Battle-Freestyle-2-768x432.jpg)