The first thing you’ll see after the studio logos appear at the start of Strange Darling isn’t the opening shot of the film’s bloodied protagonist running towards the camera in slow motion as the credits play; it isn’t even the opening text crawl, which precedes it—accompanied by a somewhat redundant voiceover reading—contextualizing the film as a recounting of mysterious (and possibly invented) serial murders taking place in Oregon between 2018 and 2020. No sir. The first thing you see onscreen in Strange Darling is one simple phrase in gray text, transposed onto the otherwise-black screen: “Shot Entirely On 35mm Film.”

Now, why a film might want to begin with such an assertion isn’t entirely clear; unless the screening in question was entirely curated by and for Christopher Nolan, what benefit is there to announce the type of film stock used to the audience of a film before we’ve even seen any of the footage in question? The simple and most likely answer is that director JT Mollner wants to make it clear from the very first moments of Strange Darling that its intermittently sumptuous presentation comes first and foremost—like any transparently shallow beauty pageant, looks do matter. That beloved character actor Giovanni Ribisi is the one in charge of cinematography here adds to the allure of the emphasis placed on this aspect of the film, as in most other respects, Mollner’s slippery slope of a film is primarily a piece of sadistically sugary eye candy above all else.

Despite the reality that Ribisi is, save for a voice cameo, working entirely behind the camera (and not even in the director’s chair, at that), his involvement in the film is its most ostensibly noteworthy aspect, if only because his name is by far the most recognizable. In front of the camera, Willa Fitzgerald carries the thrills as The Lady, a woman who, after a one-night stand with a confounding hunk credited only as “The Demon” (Kyle Gallner, embodying a solid “sadomasochistic Paul Mescal” aura—a “Sado-Mescal-ist”?), finds herself on the run from the crazed man with a rifle and a nasal cavity full of cocaine.

In the interest of maintaining the unraveling thrill structure that composes the narrative backbone of Strange Darling, the plot details won’t go any further than that, but suffice it to say that Mollner’s particular taste for cat-and-mouse antics, much in the same way as 2022’s runaway horror hit Barbarian, relishes the presence of an audience whose knowledge of what they’re getting into goes no further than what’s revealed in the first 10 minutes of the film.

What is revealed early on (and therefore can be given away with little of the experience being lost on you lucky readers) is Mollner’s decision to structure the film as a six-act tale, with an epilogue to add to the cutesy thriller framework, where those six acts aren’t even unveiled in sequential order. What could very easily devolve into a case of kitschy reveals with nothing else to offer instead allows Mollner to peel back his film with a decent amount of investment in the simplicity of the basic premise. While the film could very easily have gone an extra obnoxious step and told its various acts from different perspectives, the eventual unweaving of these narrative knots does, in fact, offer some form of direct contemplation about viewer preconceptions.

To get further into that point—and subsequently complain about specific elements of the film that are far iffier in their greater implications—would risk spoiling major plot points, but what does bear mentioning upfront is that Strange Darling, in its desire to subvert expectations, does somewhat shortchange certain characters and, as a result, certain larger demographics. Perhaps this is too deep a read into this aspect of the film (though it’s a read that wasn’t exclusive to this critic at the screening), and the very final interaction onscreen does do something to alleviate the potential accusation. But in this greater tale of horror victimhood (and particularly one that chronologically begins where it does), Strange Darling, especially by way of some directly patronizing dialogue, does run the risk of implicitly making points that vocally hateful individuals might hold up as a beacon of misplaced virtue.

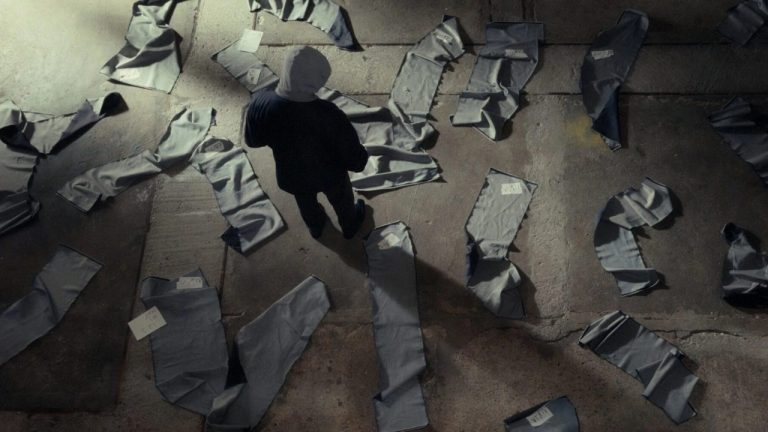

With all that said, it’s entirely possible (one would hope) that these inferences are entirely unintended byproducts of a film squarely centered on its goal to take viewers on a wild, atypical goose chase whose strengths lie in its cutthroat pacing and puzzle-piece assemblage (a structural image directly inferred onscreen in one cute visual during the second act). Amid that rocky presentation, Ribisi’s saturated lighting and (mostly) smooth camerawork go a decent way alongside Z Berg’s kitschy, lyrically direct songs in curating a playful tone for the film. Strange Darling, however, isn’t so much leaving a puzzle for viewers to assemble themselves à la Pulp Fiction as it is spreading the pieces across the floor and then reassembling them while you look on passively.

To that end, there’s certainly some low-effort enjoyment to be had in this high-energy outing, and JT Mollner’s infrastructure does at least complement the chosen narrative rather than feeling like an entirely reactionary decision as a last-ditch effort to make a bland thriller more enthralling. If one were to cut Strange Darling by its distinct acts and rearrange them chronologically, there’d still be something in the way of a messy path worth exploring, but probably one that, like the reordered version Mollner gave us, is far more compelling when the final destination is being speculated upon rather than when it’s right in front of you.

![The Father [2020] Review – A Masterclass of The Show Don’t Tell Storytelling Method](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/The-Father-1-highonfilms-768x432.jpg)

![Casino [1995] Review – A Crime Saga with Epic Scope and Memorable Characters](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Casino-1995-768x432.jpg)

![In Action [2021] Review – Bickering, self-reflective film is unbearably amateurish](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/In-Action-1-highonfilms-768x321.jpg)