In the aftermath of World War II, as Italy grappled with the physical and psychological devastation wrought by fascism and conflict, a cinematic revolution was quietly taking shape. From the rubble-strewn streets of Rome to the sun-baked countryside of Sicily, a group of visionary filmmakers turned their cameras away from the glossy artifice of pre-war Italian cinema and toward the harsh realities of everyday life. This movement, which would come to be known as Italian Neorealism, not only changed the face of Italian cinema but left an indelible mark on the global film landscape.

Born out of necessity as much as artistic vision, Neorealism emerged in a country where traditional film studios lay in ruins and resources were scarce. But from these limitations came a new aesthetic: one that embraced the raw authenticity of real locations, natural lighting, and non-professional actors. The streets became sets, and the faces of ordinary Italians, etched with the lines of hardship and resilience, became the new stars. Cameras peered unflinchingly into the lives of the working class, the unemployed, and the disenfranchised. Films tackled themes of poverty, injustice, and the struggle for dignity in a world turned upside down.

Today, in a world often dominated by spectacle and artifice, there’s a growing hunger for stories that reflect the complex realities of human experience. The best films of Italian Neorealism continue to resonate not just as historical artifacts but as living, breathing works of art that speak to the enduring struggle for dignity and connection in an often harsh world. While films in the neorealist style continue to be made today, this list of the best films from Italian Neorealism attempts to stay true to the historical span of the original movement, which ranged roughly from the early 40s to the mid-50s of the twentieth century, with film historians typically viewing the public attacks on “Umberto D. “ (1952) to indicate the waning of the movement.

20. Ossessione (1943)

Widely regarded as the first film marking the birth of Italian neorealism, Luchino Visconti’s gritty adaptation of James M. Cain’s novel 1934 “The Postman Always Rings Twice” weaves a tale of passionate obsession that would scandalize Fascist-era audiences and lay the groundwork for a new cinematic movement. The film opens with the arrival of Gino Costa (Massimo Girotti), a ruggedly handsome drifter who stumbles into a roadside trattoria run by the middle-aged Giuseppe Bragana (Juan de Landa) and his younger discontented wife Giovanna (Clara Calamai). The air crackles with unspoken tension as Gino and Giovanna lock their eyes. Their mutual attraction is immediate and palpable. Giuseppe, oblivious to the charged atmosphere, offers Gino a job and a place to stay.

Consumed by their affair, Gino and Giovanna hatch a plan to murder Giuseppe and start a new life together. In a harrowing sequence, they sabotage Giuseppe’s truck and send it careening off a cliff with him inside. The lovers’ brief moment of triumph is quickly overshadowed by guilt and paranoia as they face the consequences of their actions. Visconti’s camera lingers on the lovers’ faces, capturing every flicker of emotion as they grapple with the weight of their crime. The suffocating atmosphere of the trattoria becomes a physical manifestation of their moral decay, with shadows creeping across walls like accusing fingers. Visconti uses deep focus and long takes to draw viewers into this claustrophobic world, making us complicit in the unfolding tragedy. The oppressive heat of the Po Valley seems to radiate from the screen, while Alberto Mondadori’s haunting score underscores the characters’ growing desperation.

19. Il Grido (1957)

Although released in 1957 after the waning of neorealism’s peak, Antonioni had written the script for “Il Grido” as early as the late 40s when the movement was in its heyday. As such, the film stands as a pivotal work in Antonioni’s oeuvre, bridging his earlier works with the groundbreaking alienation trilogy that would follow. At the heart of “Il Grido” is Aldo (Steve Cochran), a refinery worker whose world implodes when his longtime lover Irma (Alida Valli) announces she no longer loves him. With his seven-year-old daughter Rosina (Mirna Girardi) in tow, Aldo embarks on a meandering journey through the Po Valley, a quest for meaning that becomes an odyssey of the soul.

Antonioni’s camera follows Aldo’s wanderings with a detached yet empathetic gaze, capturing the desolate beauty of the landscape as it mirrors the protagonist’s emotional state. Aldo’s first stop is the home of Elvia (Betsy Blair), a former flame who still harbors feelings for him, but Aldo’s inability to connect drives him away once more. The journey continues, each encounter revealing another facet of Aldo’s deepening alienation. He finds temporary solace with Virginia (Dorian Gray), a young gas station attendant whose youthful vitality stands in stark contrast to Aldo’s world-weary demeanor, yet even this respite proves fleeting. While still rooted in neorealist traditions, “Il Grido” showcases Antonioni’s growing preoccupation with the inner landscapes of his characters. Long, unbroken takes and carefully composed frames create a sense of time suspended, mirroring Aldo’s aimless drift through life.

18. Roma 11:00 (1952)

Based on a real accident that took place the previous year, Giuseppe De Santis’s “Roma, ore 11” opens on a sweltering Roman morning as a throng of women, young and old, converge on a nondescript building in the heart of the city. They’ve come in response to a newspaper ad offering a secretarial position – a rare opportunity in a time of widespread unemployment. As the crowd swells, tensions rise, and the atmosphere grows thick with desperation and rivalry. De Santis introduces us to a cross-section of Italian society through his diverse cast of characters, representing all shades, from wives supporting invalid husbands to former sex workers. As the women wait, their stories unfold through a series of vignettes and flashbacks. We see glimpses of their lives – the hardships, the dreams, the compromises they’ve made to survive.

The film’s pivotal moment comes at 11:00 AM when the overcrowded staircase in the building suddenly collapses, plunging dozens of women into chaos and tragedy. In a heart-stopping sequence, De Santis captures the panic and horror of the accident with documentary-like precision. The camera doesn’t flinch as bodies tumble and screams pierce the air, creating a visceral experience that leaves viewers shaken. As rescue efforts drag on, journalists descend on the scene, more interested in crafting salacious headlines than in the human cost of the tragedy. “Roma 11:00” is a damning portrait of a society where human life is cheap and the pursuit of profit trumps all other concerns, drawing clear parallels between the cutthroat competition for the secretarial job and the broader struggles of post-war Italy.

17. Journey to Italy (1954)

Marking a significant development over Roberto Rossellini’s earlier neorealist works and preparing the ground for a shift away from them, “Journey to Italy” is a deceptively simple yet profoundly affecting exploration of a marriage in crisis, set against the backdrop of Naples and its surrounding ancient landscapes. The story follows the Joyces, a British couple, who travel to Italy to sell a villa inherited from Alex’s uncle. Their car ride from Rome to Naples is fraught with terse exchanges and loaded silences, each word and gesture hinting at years of unspoken resentments and growing emotional distance. Once in Naples, Katherine (Ingrid Bergman) and Alex (George Sanders) find themselves adrift in a foreign culture that seems to magnify their own alienation from each other.

The bored and restless Alex seeks distraction in the company of other expatriates and potential romantic dalliances. Meanwhile, Katherine immerses herself in the rich history and culture of the region, visiting museums and archaeological sites that spark introspection about her life and marriage. Rossellini’s camera follows her as she wanders through the National Archaeological Museum, lingering on ancient statues that seem more alive and passionate than her own husband. In a particularly poignant scene, Katherine visits the crater of Vesuvius, the desolate landscape mirroring her inner turmoil. Rossellini foregoes traditional narrative structure in favor of a more episodic approach, allowing moments of quiet contemplation to build into a powerful emotional crescendo. Rossellini’s achievement lies in making us feel the full weight of a marriage’s history in a glance, a hesitation, a moment of unexpected tenderness amidst the ruins of the past.

16. Bitter Rice (1949)

De Santis presents a pulsating blend of neorealist melodrama with “Bitter Rice,” set against the backdrop of the Po Valley rice fields, concocting a heady mix of crimes of passion and social commentary. It sets off with a jolt of adrenaline as we meet Francesca (Doris Dowling), a sharp-tongued thief on the run with her ne’er-do-well lover Walter (Vittorio Gassman). In a desperate bid to evade the law, Francesca blends in with a group of mondine – seasonal rice field workers – heading north for the harvest. Here, she encounters the vivacious Silvana (Silvana Mangano), a mondina whose smoldering sexuality and unbridled zest for life practically leap off the screen.

As the women wade into the flooded rice paddies, De Santis’s camera drinks in the sight of their glistening bodies, creating a visual feast that teeters on the edge of exploitation. Yet beneath this veneer of sensuality lies a biting critique of the harsh working conditions and social inequalities faced by these women. The plot thickens when Walter resurfaces, his predatory gaze fixed on the alluring Silvana. Meanwhile, the honest and hardworking soldier Marco (Raf Vallone) finds himself drawn to Francesca, sensing the goodness buried beneath her tough exterior. De Santis masterfully weaves together multiple narrative threads, each pulsing with its own energy. There’s the crime plot, as Walter schemes to steal the rice crop. There’s the love story, or rather stories, as hearts are won, lost, and reclaimed. And underlying it all is a stark portrayal of class struggle, with the mondine fighting for fair wages and better conditions.

15. Stromboli (1950)

Marking Ingrid Bergman’s first collaboration with director Roberto Rossellini, Stromboli’s uncompromising exploration of cultural alienation and spiritual crisis is forged through blending neorealist techniques with a deeply personal narrative, blurring lines between art and life. In a desperate bid to escape a displaced persons camp, Lithuanian refugee Karin (Ingrid Bergman) marries Antonio (Mario Vitale), an Italian ex-POW fisherman. Karin’s hope for a better life quickly sours as she finds herself transplanted to Antonio’s home on Stromboli, a volcanic island off the coast of Sicily. As Karin struggles to adapt to life on the island, her relationship with Antonio deteriorates, and the cultural chasm between them seems vast and unbridgeable.

From the moment Karin sets foot on the island, Rossellini immerses us in a world of stark contrasts. The harsh lunar landscape of Stromboli, with its black sand beaches and looming volcano, serves as a physical manifestation of Karin’s internal desolation. Bergman’s face becomes a canvas for a myriad of emotions – hope, disgust, desperation, and ultimately, a kind of transcendent awe. The daily lives of the islanders – the grueling tuna fishing expeditions, the rhythms of village life – are depicted with documentary-like precision.

Yet the film also has a heightened, almost expressionistic quality, particularly in its depiction of the volatile relationship between Karin and her surroundings. The film builds to a climax of near-mythic proportions as the volcano erupts, forcing the villagers to evacuate. Rossellini masterfully alternates between tightly framed close-ups that capture every nuance of Bergman’s performance and wide shots that emphasize the vastness of the landscape and Karin’s isolation within it.

14. Bellissima (1951)

With the bittersweet satire “Bellissima,” Visconti deftly peels back the glittering façade of the Italian film industry to reveal both dreams and delusions underlying it. At once a scathing critique of cinema’s exploitative nature and a tender portrait of maternal love, the film showcases Visconti’s ability to blend neorealist grit with the heightened emotions of melodrama. Maddalena Cecconi (Anna Magnani) is a working-class mother in post-war Rome who becomes obsessed with the idea of turning her young daughter Maria (Tina Apicella) into a movie star. When Cinecittà Studios announces an open casting call for a new child actress, Maddalena sees it as her ticket out of poverty and obscurity.

The film’s first half unfolds like a darkly comic odyssey through the underbelly of the film industry. Maddalena pawns her wedding ring to pay for dancing lessons, endures the condescension of casting agents, and even resorts to bribing a studio electrician for inside information. Each setback only fuels her determination, even as it chips away at her dignity. Visconti’s camera captures every nuance of Magnani’s expressive face, from the fierce determination as she coaches her daughter to the flickers of doubt and vulnerability that betray her most profound insecurities. His keen eye for social observation is evident in the way he contrasts the cramped and bustling working-class neighborhoods with the cavernous, impersonal spaces of Cinecittà. The scenes of mass auditions, with hundreds of mothers pushing their bewildered children forward, are a masterclass in controlled chaos.

13. The Children Are Watching Us (1943)

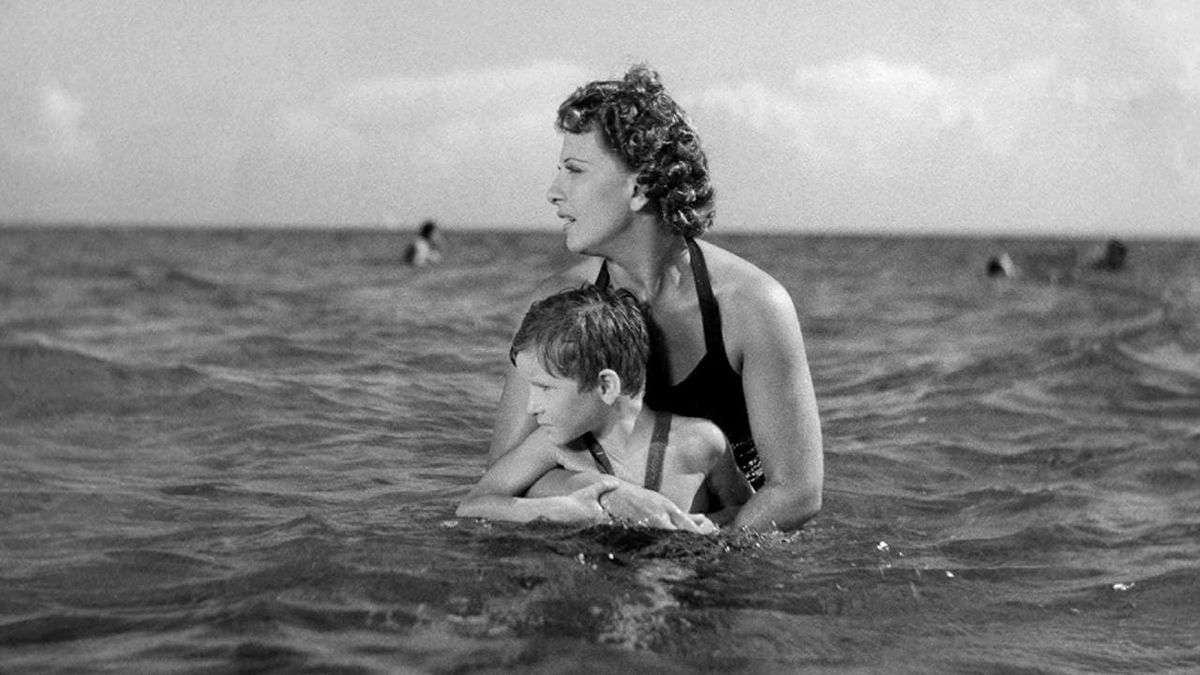

An often-overlooked gem from De Sica’s oeuvre, “The Children Are Watching Us” serves as a poignant prelude to his later neorealist masterpieces, combining a keen eye for social observation with a deeply empathetic portrayal of a child’s emotional world. The film centers on Pricò (Luciano De Ambrosis), a sensitive five-year-old boy whose world is upended by his mother, Nina’s (Isa Pola) infidelity and his father, Andrea’s (Emilio Cigoli) inability to cope with the fallout. De Sica establishes a sense of unease from the opening scenes, with the camera often positioned at Pricò’s eye level, allowing us to experience the adult world through his bewildered gaze.

As Andrea struggles to hold the family together, Pricò is shuttled between relatives and caretakers. Each new environment brings its own challenges, from the stern discipline of his aunt to the false cheer of a seaside boarding house. De Ambrosis delivers a remarkably naturalistic performance, his expressive eyes conveying a depth of emotion that belies his young age. The film’s most powerful scenes are often its quietest: Pricò silently watching his father break down in tears, the child’s face a mask of confusion and helpless empathy. De Sica pulls no punches in showing how Pricò’s parents, trapped in their own emotional turmoil, fail to see the damage they’re inflicting on their son. The film’s title takes on an accusatory tone, reminding us that children are not passive observers but active participants in family dramas, absorbing and internalizing every conflict.

12. The Flowers of St. Francis (1950)

Roberto Rossellini’s “The Flowers of St. Francis” is a luminous and unconventional exploration of faith, offering a series of vignettes that capture the essence of St. Francis of Assisi and his early followers with disarming charm and profound spirituality. The film unfolds as a collection of episodes loosely based on the 14th-century text “Little Flowers of St. Francis.” Rather than presenting a traditional biopic, Rossellini focuses on small, often humorous incidents that illuminate the saint’s teachings and the struggles of his disciples to embody them. This episodic structure creates a sense of timelessness, almost as if we’re witnessing moments plucked from eternity.

At the heart of the film is Brother Francis (played with guileless simplicity by Brother Nazario Gerardi), portrayed not as a lofty religious figure but as a man of profound joy and childlike wonder. Rossellini’s Francis giggles, stumbles, and radiates an infectious enthusiasm that makes his spiritual wisdom all the more potent. In one memorable scene, Francis preaches to a flock of birds, his face alight with genuine delight at God’s creation. Rossellini’s direction is marked by a stripped-down aesthetic that perfectly complements the film’s themes. Long takes and simple compositions create a sense of quiet contemplation. At the same time, the use of natural light and real locations (including the ruins of Tuscania) imbues the film with an earthy authenticity. This visual approach, coupled with the use of non-professional actors (many of them real Franciscan monks), creates a unique blend of the historical and the immediate.

11. Europa ’51 (1952)

Blending neorealist elements with a deeply personal exploration of faith, madness, and social responsibility, Rossellini’s “Europa ‘51” remains a searing examination of post-war European society. The film opens in the rarified air of a bourgeois dinner party, where Irene’s (Ingrid Bergman) brittle laughter and distracted manner hint at the emptiness lurking beneath her privileged existence. Tragedy strikes when her young son Michel (Sandro Franchina) is severely injured upon falling down a staircase. His subsequent death becomes the catalyst for Irene’s radical transformation. A chance encounter with a communist journalist named Andre (Ettore Giannini) opens her eyes to the suffering of Rome’s poor, and she begins to devote herself to helping others with a fervor that borders on obsession.

Rossellini’s camera follows Irene as she descends into the city’s underbelly, capturing the stark realities of post-war poverty with unflinching clarity. She gives away her possessions, neglects her appearance, and spends her nights wandering the streets in search of those in need. Bergman’s portrayal of Irene’s growing disconnect from societal norms is both unsettling and deeply moving, her eyes blazing with a fervor that teeters between saintly compassion and madness. Rossellini draws explicit parallels between Irene and religious mystics, notably St. Francis of Assisi, challenging viewers to consider where the line between madness and sainthood truly lies. As Irene’s journey progresses, the cinematography becomes increasingly dreamlike, mirroring her detachment from conventional reality. The film’s indictment of a society that views selfless compassion as a form of insanity is as pointed as it is poignant.

Related to Italian Neorealism: Martin Scorsese’s 10 Favourite Films of All Time

10. Miracle in Milan (1951)

De Sica’s “Miracle in Milan” is a whimsical fairy tale dancing on the razor’s edge between neorealist grit and magical fantasy. The film challenges viewers to see the world through eyes unclouded by cynicism with its uniquely layered narrative of social commentary and childlike wonder. We follow the adventures of Totò (Francesco Golisano), an orphan with an irrepressible optimism and a heart full of love for his fellow man. Found as a baby in a cabbage patch by the kindly Lolotta (Emma Gramatica), Totò grows up believing in the inherent goodness of people and the power of simple kindness. Golisano’s performance is a marvel of wide-eyed innocence, his expressive face radiating a joy that’s as infectious as it is improbable given his circumstances.

After Lolotta’s death, Totò finds himself in an orphanage, where his unfailing cheerfulness confounds the stern nuns. Upon his release, he wanders into a shantytown on the outskirts of Milan, a stark landscape of poverty that De Sica captures with the same unflinching eye he brought to “Bicycle Thieves.” Yet here, amidst the squalor, Totò sees only possibility. A series of increasingly fantastical episodes follows as Totò transforms the shantytown into a community bound by love and mutual aid. De Sica’s direction shines in his ability to seamlessly blend the real and the fantastical. One moment, we’re witnessing the harsh realities of post-war poverty, and the next, we’re watching Totò multiply loaves of bread or summon warm clothing for the freezing inhabitants. Perhaps most significantly, these miracles are presented matter-of-factly, as if kindness itself is the most natural magic in the world.

9. Paisan (1946)

The second film from Rossellini’s famed War Trilogy, “Paisan” weaves together six distinct episodes that chart the Allied advance from Sicily to the Po Valley, creating a mosaic of human experiences that captures the chaos, tragedy, and occasional moments of connection in a country torn apart by conflict. Rather than following a traditional narrative arc, the film presents a series of vignettes, each set in a different region of Italy and focusing on the interactions between Allied soldiers and Italian civilians. This episodic structure allows Rossellini to paint a broader picture of the war’s impact while also delving deep into individual stories of loss, misunderstanding, and fragile hope.

The film opens in Sicily, where an American patrol, guided by a local girl named Carmela (Carmela Sazio), becomes embroiled in a tense standoff with German forces. The language barrier between Carmela and Joe (Robert Van Loon), a young GI, leads to a tragic misunderstanding that sets the tone for the cultural clashes that will recur throughout the film. Moving north to Naples, we encounter a drunk African American MP (Dots Johnson) who forms an unlikely bond with a street urchin (Alfonsino Pasca). The Rome episode is perhaps the most poignant, following six months in the life of sex worker Francesca (Maria Michi) and Fred (Gar Moore), an American soldier who had a brief encounter with her during the liberation of Rome. Rossellini’s camera doesn’t flinch from the harsh realities of war – bombed-out cities, starving children, and the ever-present specter of sudden violence.

8. I Vitelloni (1953)

Capturing the aimless malaise of five young men in a sleepy Italian coastal town, “I Vitelloni” is Federico Fellini’s bittersweet ode to arrested development. The story revolves around Fausto (Franco Fabrizi), Moraldo (Franco Interlenghi), Alberto (Alberto Sordi), Leopoldo (Leopoldo Trieste), and Riccardo (Riccardo Fellini, the director’s brother). These overgrown boys, hovering around their thirties, while away their days in cafes, poolrooms, and dancehalls, perpetually dodging responsibility and dreaming of escape from their provincial lives. The plot kicks into gear when Fausto, the group’s lothario, impregnates Sandra (Leonora Ruffo), Moraldo’s sister. Forced into a shotgun wedding, Fausto briefly attempts to embrace adulthood, taking a job at his father-in-law’s shop. However, his philandering ways soon resurface, leading to a series of misadventures that ripple through the group.

Fellini’s direction is a masterclass in tragicomedy, effortlessly blending moments of raucous humor with piercing melancholy. The carnival sequence, where the vitelloni drunkenly taunts working men before fleeing in comedic terror, exemplifies this tonal balancing act. It’s at once hilarious and painfully revealing of the characters’ immaturity and class privilege. While still rooted in neorealist aesthetics, with its use of location shooting and non-professional actors, “I Vitelloni” hints at Fellini’s burgeoning surrealist tendencies. It’s a coming-of-age story where no one quite comes of age, a pointed critique of masculinity and small-town inertia. Fellini dissects the vitelloni’s arrested development with a mix of affection and disdain, understanding their dreams of escape while condemning their selfishness and casual cruelty.

7. Germany Year Zero (1948)

“Germany Year Zero” completes Rossellini’s War Trilogy with a haunting portrayal of post-war Berlin, unflinchingly viewed through the eyes of a child. Set amid the rubble of a defeated Germany, the plot follows 12-year-old Edmund Koeler (Edmund Moeschke), a boy prematurely thrust into adulthood by the harsh realities of survival in a broken city. Edmund’s family barely subsists in a cramped, bombed-out apartment: his father (Ernst Pittschau) is bedridden and severely ill, his brother Karl-Heinz (Franz-Otto Krüger) hides from authorities, fearing arrest for his involvement in the Nazi regime, and his sister Eva (Ingetraud Hinze) resorts to consorting with Allied soldiers for cigarettes and small luxuries.

As Edmund wanders through Berlin’s war-ravaged landscape, scavenging and hustling to support his family, Rossellini’s camera follows him with a documentary-like authenticity that’s almost unbearable in its starkness. We see Edmund digging graves, stealing food, and engaging in the black market – images evoking childhood innocence corrupted by necessity. The film’s style is stripped down to its essentials – long takes, natural lighting, and a near-absence of non-diegetic music (save for the occasional, jarring use of a German children’s song). Moeschke’s untrained acting lends an authenticity to Edmund that professional child actors of the time might have struggled to achieve. “Germany Year Zero” is both an indictment of Nazism and its lingering influence and a compassionate portrayal of German suffering. Rossellini walks a tightrope, condemning the ideology that led to war while highlighting the human cost of its aftermath.

6. Shoeshine (1946)

Vittorio De Sica’s early masterpiece “Shoeshine” centers on two young boys, Giuseppe (Rinaldo Smordoni) and Pasquale (Franco Interlenghi), inseparable friends who eke out a living shining American soldiers’ shoes. Their dream? To buy a magnificent white horse, they’ve been eyeing. With a mix of childish exuberance and street-smart hustle, they scrimp and save, their goal tantalizingly within reach. But fate, as it often does in neorealist cinema, has other plans. The boys’ older acquaintances rope them into a scheme to sell stolen American blankets. Blinded by the prospect of quick cash to secure their equine prize, Giuseppe and Pasquale agree. The plan goes awry when the boys are arrested and thrown into a juvenile detention center, a labyrinthine hell that forms the backdrop for much of the film’s gut-wrenching drama.

Inside the prison’s oppressive walls, De Sica’s camera prowls restlessly, capturing the claustrophobia and simmering violence of this child-populated purgatory. Giuseppe and Pasquale, once united, find their bond tested by the brutal dynamics of incarceration. Their struggles are compounded by a legal system more interested in expediency than justice and adults who view the boys as either nuisances or tools for their own agendas. Cinematographer Anchise Brizzi’s handheld camera work lends an immediacy and documentary-like quality to the proceedings. The bombed-out streets of Rome and the dank corridors of the detention center are captured with an unflinching eye, the city itself becoming a character – one that has chewed up and spit out these children.

5. La Terra Trema (1948)

Visconti presents a blistering portrait of a Sicilian fishing village caught in the grip of economic exploitation with the docufictional “La Terra Trema” (“The Earth Trembles”). At once a Marxist parable, a naturalistic slice of life, and a visual poem to the rugged beauty of Sicily and its people, the film centers on the Valastro family, led by the young and idealistic ‘Ntoni (Antonio Arcidiacono). Frustrated by the exploitative practices of the local wholesalers who control the price of fish, ‘Ntoni convinces his family to mortgage their home and strike out on their own. His grandfather (Giovanni Greco) and siblings – including his sisters Mara (Nelluccia Giammona) and Lucia (Agnese Giammona) – reluctantly agree, seduced by the promise of independence and prosperity.

We watch as the family hauls in bountiful catches, their faces alight with hope and pride, and the gamble seems to pay off initially. But Visconti, true to his Marxist leanings, doesn’t allow this idyll to last. A violent storm destroys their boat and, with it, their dreams of autonomy. Visconti employs long takes and wide shots that allow the drama to unfold organically, capturing the rhythms of village life with documentary-like precision. Yet there’s a painterly quality to his compositions – scenes of fishermen hauling in nets against a stormy sky or women gossiping in sun-drenched alleys evoke the grandeur of classical art. “La Terra Trema” pushes the boundaries of what neorealism could achieve, maintaining a commitment to social reality while aspiring to the scope and beauty of epic cinema.

4. Bicycle Thieves (1948)

Set against the backdrop of a Rome still reeling from the ravages of World War II, Vittorio De Sica’s “Bicycle Thieves” follows two days in the life of Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani), a man whose quest to recover his stolen bicycle becomes a heart-wrenching odyssey through the city’s unforgiving streets. The film opens with hope as Antonio, unemployed and destitute, is offered a job posting movie bills. But the catch is that he needs a bicycle for the job. His wife Maria (Lianella Carell) strips their bed of its sheets, pawning them to reclaim Antonio’s bicycle. For a brief, shining moment, the family’s fortunes seem to be on the upswing. Yet his precious bicycle is stolen on Antonio’s first day of work.

Accompanied by his young son Bruno (Enzo Staiola), Antonio embarks on a desperate search through Rome’s neighborhoods. Their journey takes them from bustling markets to rain-soaked streets, from a fortune teller’s den to a brothel, each location a microcosm of a society struggling to rebuild itself. This father-son relationship forms the film’s emotional core, with Bruno’s unwavering faith in his father contrasting poignantly with Antonio’s growing self-doubt. The film asks: In a world of widespread poverty, who is truly guilty – the thief or the system that creates such desperate circumstances? This moral ambiguity comes to a head in the film’s gut-wrenching climax, where Antonio, driven to despair, attempts to steal a bicycle himself – offering the cruelest twist imaginable to the film’s title.

3. La Strada (1954)

Fellini’s tale of a simple-minded young woman sold to a brutish strongman proves to be at once a devastating portrait of human cruelty and a transcendent exploration of love in “La Strada,” a film bridging his former neorealist origins with his later fantastical and personal cinema. It follows Gelsomina (Giulietta Masina), a wide-eyed innocent whose poverty-stricken mother sells her to Zampanò (Anthony Quinn), a traveling strongman. Zampanò’s act consists of breaking an iron chain wrapped around his chest, a fitting metaphor for his constrained emotional state. As they travel the desolate Italian countryside in a ramshackle motorbike and trailer, Gelsomina attempts to connect with the world through her childlike wonder and nascent talent for music and clowning. Zampanò, however, treats her with casual cruelty, seeing her as little more than a servant and occasional bedmate.

Their troubled dynamic is further complicated by the appearance of Il Matto (“The Fool”), played with impish charm by Richard Basehart. A high-wire artist, Il Matto recognizes something special in Gelsomina and becomes both her defender and tormentor of Zampanò. Fellini infuses the stark, neorealist-influenced landscapes with touches of the surreal and mythic. His compositions often place his characters against vast, empty landscapes, underlining their emotional and spiritual desolation. A scene where Gelsomina plays her trumpet to a curious child in an abandoned village square becomes a moment of near-religious transcendence, the barren setting transformed by the purity of human connection. The film is notable for winning the inaugural Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1957.

2. Rome, Open City (1945)

The first film from Rossellini’s War Trilogy is a visceral cry of defiance that emerged from the ashes of World War II, heralding the birth of Italian Neorealism and forever changing the landscape of cinema. Shot on the streets of Rome mere months after the city’s liberation from Nazi occupation, the film pulses with an urgency and authenticity that still resonates nearly eight decades later. At its center is the charismatic Giorgio Manfredi (Marcello Pagliero), a Communist resistance leader on the run from the Gestapo. He finds refuge with Francesco (Francesco Grandjacquet), a typesetter, and his fiancée Pina (Anna Magnani), a pregnant widow whose fierce maternal instincts extend to protecting her community.

Parallel to their story runs that of Don Pietro Pellegrini (Aldo Fabrizi), a Catholic priest who aids the resistance despite his ideological differences with the Communists. His moral conviction that fighting oppression supersedes political divisions becomes a central theme of the film. Working with limited resources and film stock, Rossellini turns necessity into virtue, embracing a documentary-like aesthetic that lends the film its searing conviction. The real-life experiences of the cast and crew during the occupation infuse every performance with a lived-in authenticity that no amount of method acting could replicate. The film’s structure, with its multiple storylines and ensemble cast, prefigures later works like “Battle of Algiers” and even contemporary TV dramas in its portrayal of resistance as a collective effort rather than individual heroism.

1. Umberto D. (1952)

Perhaps the crowning jewel of Italian neorealism at its peak, De Sica’s “Umberto D.” transforms the quiet struggles of a pensioner into a profound meditation on dignity and loneliness, portraying one man’s fight against poverty and obsolescence. The titular Umberto Domenico Ferrari (Carlo Battisti) is a retired government clerk struggling to survive on a meager pension in post-war Rome. His world has shrunk to a rented room in a boarding house run by the unsympathetic Antonia (Lina Gennari), his sole companions being his beloved dog Flike and Maria (Maria Pia Casilio), the young housemaid who occasionally shows him kindness. As the film progresses, Umberto’s situation grows increasingly desperate. Unable to pay his rent, he faces eviction.

Umberto’s attempts to raise money, from pawning his possessions to a half-hearted attempt at begging, are exercises in humiliation. Even a brief hospital stay becomes a bittersweet respite, offering the warmth and care so lacking in his daily life. A 70-year-old university professor in real life, first-time actor Carlo Battisti brings a quiet dignity to Umberto that makes his struggles all the more poignant. The film stands as a damning indictment of a society that discards its older populace, a meditation on the nature of dignity, and an exploration of the thin line between perseverance and despair. De Sica asks us to consider: What is the worth of human life when stripped of social status and material possessions? Unlike “Bicycle Thieves,” with its more overt social commentary, “Umberto D.” achieves its power through an accumulation of small, painfully human moments.