Cinema based on LGBTQ+ issues has become mainstream in the 21st Century, with films like Moonlight, A Fantastic Woman, and 120 BPM heading a much-required discourse on queer identity politics and representation. But, if we look at the history of LGBTQ+ cinema back in the 20th Century, we would see how this representation came into being.

During the classical Hollywood era from the early 1920s to the late ‘50s, homosexuality was only understood through propagating stereotypes and reinforcing them through innuendos. Homosexuals were perceived to exhibit feminine features such as being soft-spoken, moving about in a “dainty” fashion, or being physically weaker than the male protagonist. In 1980 “Cruising” was released that featured a murderous psychopath among an S&M New York subculture where there was a direct link between homosexual insinuations and crime.

Considering these facts, where is the balance between depicting a queer antagonist and LGBTQ visibility? Can evil characters be queer without the filmmakers being perceived as homophobic? This list takes a look at the films that have shaped the mainstream conception about LGBTQ issues through a variety of topics revolving around queerness in the 20th Century. These films are ranked based on their year of theatrical release and chart an evolution in the way in which queer characters are portrayed.

Honorable Mention:

• Fireworks (1948) • My Hustlers (1965) • Fox and his Friends (1975) • Laws of Desire (1988) • Longtime Companion (1989)

1. Mädchen in Uniform (1931)

Mädchen in Uniform, which translates from German to Girls in Uniform, is a landmark of feminist cinema and queer cinema, as well as the late Weimar-era German cinema. Based on a successful play by lesbian author Christa Winsloe and featuring an all-female cast, it begins with the arrival of “overly sensitive” 14-year-old Manuela (23-year-old Thiele in an enthralling performance) at an authoritarian Prussian boarding school where the girls’ pubescent yieldings are all pointed towards a crush on the popular teacher Fräulein von Bernburg (Wieck). Manuela’s passion for the strict but loving schoolmistress quickly escalates beyond the level of a harmless crush, threatening the school’s delicate balance of repression and indulgence.

Mädchen in Uniform is also a boldly anti-totalitarian parable. The headmistress (Emilia Unda) bears a stubborn view of her charges as “daughters of soldiers and, God willing, soon again mothers of soldiers.” When she proudly describes the students as “raised on hunger,” Sagan cuts immediately to a scene of the girls discussing their favorite types of pastry.

Related to Queen Movies – The 10 Best LGBT Movies of 2018

The headmistress keeps her version of the school and the real one from colliding by examining any outgoing letters and punishing girls who have written complaints. Recent years of queer film archaeology have determined this to be the first truly radical and explicit lesbian film. Girls in Uniform brilliantly details how our emotions and desires are forever policed, even down to the minutest details of our everyday lives, queer or not.

2. Un Chant d’amour (1950)

In the 1940s, Jean Genet’s film Un Chant d’Amour (A Love Song), was banned in the U.S., charged with being “cheap pornography calculated to promote homosexuality, perversion and morbid sex practices.” Genet was a queer French novelist, playwright, and adult prisoner, sex worker, essayist, and activist. His work deals with queer sexuality, criminalization, and imprisonment.

Un Chant d’Amour focuses on two inmates who live in adjacent cells and are in love. They communicate by blowing cigarette smoke through a hole in their shared wall- a scene considered one of the most sensual moments in the history of cinema. The prison guard secretly watches them fantasize about one another and becomes increasingly jealous of their lust.

Similar to Queer Movies – The 15 Best LGBTQ Films Of 2017

This revolutionary film successfully explores not only themes of forbidden love, desire, homosexuality, and fantasy, but also desperation, captivity, and repression – in under half an hour. Un Chant d’Amour is not just important as a perfect introduction to the powerful effects of isolation and violence that queer prisoners on the other side of the letter correspondence are fighting but also as a truly beautiful piece of filmmaking – one that is as artistically attuned and emotionally moving.

3. Some Like It Hot (1959)

Billy Wilder’s Some Like it Hot is one of those movies that remains important not as a direct manifestation of queer issues but as a cunning subversion of the mainstream understanding of it altogether. Its relevance lies in the carnivalesque treatment of the chaotic defiance of social mores and sexual norms. Some Like It Hot is essentially a film about masquerade, and under the guise of an early Hollywood gangster flick, the film parodies the conventions of that genre while simultaneously shrouding itself in the iconography of a more liberated era.

Saxophonist Joe (Tony Curtis) and double-bass player Jerry (Jack Lemmon), accidentally witness a fictionalized version of the St Valentine’s Day Massacre. Realizing that there is nowhere to hide in cold, snowy Chicago, the pair don wigs and dresses, disguise themselves as female musicians and join an all-girl band headed for balmy Florida. Costume and performance lie at the heart of Some Like It Hot. Its two lead characters are musicians, performers, who eagerly transform their personas in order to play gigs.

Related to Queer Movies – 25 Feel-Good Movies and where to watch them

The inversion of gender identity sits at the heart of Some Like It Hot. This transgression of gender norms is perhaps the most Shakespearean element of a film whose reliance on confusing plotlines and complex wordplay owe more than a little to the bard’s comedies like As You Like It and Twelfth Night. As a film produced in the 1950s, it had neither the freedom nor the vocabulary to talk about these issues. However, what it succeeds in doing is troubling and undermining the entrenched – and, at the time, powerful – categories of male/female or gay/straight.

4. The Children’s Hour (1961)

William Wyler’s adaptation of the Lillian Hellman play, The Children’s Hour was an important addition in the queer representation in Cinema. It told the story of Karen Wright and Martha Dobie, two life-long friends who run an all-girls boarding school. One of their students, the mischievous and deceitful Mary, begs her grandmother to leave the school; she presents a simple lie: that the two women have an “unnatural” relationship and that she saw them kissing on Karen’s bed.

Mary’s grandmother immediately pulls her from the school and spreads the word; other parents the following suit. Starring Audrey Hepburn as Karen, Shirley MacLaine as Martha, and James Garner as Joe, The Children’s Hour is good if a bit melodramatic, the drama that depicts how an unfortunate combination of gossip and a puritanical culture can destroy innocent lives.

Related to Queer Movies – Dead to Me (Season 2) Netflix Review – An Ode to Women

In order to uphold institutional ideals and avoid such potential “injury” of uncontrolled (sexual) knowledge, we see a number of efforts to police sexuality and reinforce heteronormativity throughout The Children’s Hour: girls within the school are reminded during a sewing and elocution lesson that “courtesy is breeding and breeding is most to be desired in a woman. It is what every man wants in a woman”. Karen and Martha’s friendship is policed by the community at large, and Martha effectively polices herself through confession, expression of shame, and ultimate suicide.

While these numerous references to “breeding” within The Children’s Hour do reinforce “the eugenic ideal of controlled reproduction […]” But what still remains problematic is how the film deals with queerness as a topic that needs to be silenced, where the self-loathing quality in the characterization of the lesbian still illustrated the need to eliminate the queer.

The discrimination against the homosexual in Wyler’s The Children’s Hour was not fully revealed until a documentary film, The Celluloid Closet, contained in an interview with Shirley MacLaine, who admitted to the silencing of the queer in the film through not portraying a more progressive mentality. It is not until recent adaptations, such as the 2011 stage adaptation, that audiences and artists have explored the possibility of acceptance, rather than the elimination of the queer.

5. Victim (1961)

Basil Dearden’s Victim is a fascinating time capsule of a film that is a landmark in terms of queer representation in cinema wrapped up as a thriller. The Sexual Offences Act 1967 decriminalized homosexual relations in England and Wales between two consenting adults over the age of 21. Victim helped in a tectonic shift of attitude towards homosexuality and resulted in a change in the law. Lord Arran, a Conservative politician who saw the film on Television, and whose own gay brother had committed suicide, wrote to Bogarde saying that Victim had contributed to a swing in support for reform from 48 percent to 63 percent.

Victim was the first British-made film to focus its narrative on homosexual men not as criminals but as victims of a pernicious law. It was also the first British film in which a character utters the word “homosexual” and to feature a teenager who is openly identified as being gay. It was about a young wage clerk who is arrested after drawing fictitious salaries to pay off a blackmailer threatening to release a compromising photograph of him with another man. The other man is Melville Farr, a married London barrister played by a 39-year-old Dirk Bogarde, then at the peak of his fame as a matinee idol. What started this revolutionary change in perception was its message of tolerance, which cut through the parameters of prejudice.

6. The Killing of Sister George (1968)

Killing Of Sister George (1968) is often spoken of in the same breath with The Boys In The Band (1970) because both share a certain notoriety for being hysterically negative representations of queers on the silver screen. It revolves around an aging lesbian television actress, June “George” Buckridge (Beryl Reid, reprising her role from the stage play), who faces the loss of her popular television role and the breakdown of her long-term relationship with a younger woman (Susannah York). It remains a lesbian cult classic that has the distinction of being the first “serious” film to receive an X rating.

The core of the film, that is George and Childie’s relationship is defined by outrageous sadomasochistic ritual (Childie must kneel before George and eat the butt of her cigar to show contrition) and, at times, outright abuse (Childie is struck by a scone hurled by George during Mrs. Croft’s first visit to their flat).

Also Related to Queer Movies – 10 Unconventional Films About Teenage Girls

At the time of its release, this aspect of portrayal and the lovemaking scenes were controversial and it flopped at the box office but through the ages, The Killing of Sister George has turned into a cult classic, for showing the dominant-submissive equation in a queer relationship in a celebratory, nonchalant manner. “Not all girls are raving bloody lesbians, you know,” Childie snarls at George during one of the latter’s jealous rages. “That is a misfortune that I am perfectly well aware of,” the tubby woman retorts, never compromising on her sexuality for the stereotypes of her age.

7. Death in Venice (1971)

This queer classic is based on Thomas Mann’s novel and revolves about a middle-aged heterosexual artist Gustav von Aschenbach (played by Dirk Bogarde) vacationing in Venice who becomes obsessed with a youth Tadzio (Björn Andrésen), staying at the same hotel as a wave of cholera descends upon the city. What he finds in this adolescent boy is a physical perfection so captivating that he embarks on an obsessive pursuit destined to destroy him.

As glamourized as it was made back when it released, it must be noted that the fact that “Death in Venice” is based to some degree on an event from Mann’s life, and even the fact that Mann himself may have been homosexual or bisexual, does not mean that the book and this subsequent adaptation is only about those things, or that it amounts to no more than an image of hidden desires. The reason why Death in Venice still stands the test in time is greater than the performance by Dirk Bogarde, who was at the pinnacle of his career then.

Related to Queer Movies – Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019) Review – The Intimate Charm of an Aristocracy

Its greatness echoes from the identification with his character ok screen, even to feel uplifted as he is uplifted by his vision of Tadzio’s purity. His obsession is complex; as much aesthetic as sexual it also seems to represent a longing for the youthfulness that has left him and for the creative potential that entailed; and, perhaps, its self-destructive nature is also part of its appeal. It is a deeply enchanting film that treats love as a mystery, ahead of gender conventions.

8. The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant (1972)

Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 12th feature film Die bitteren Tränen der Petra von Kant (The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant) is largely autobiographical and is based on Fassbinder’s relationship with an actor. It revolves around Petra who is a self-absorbed fashion designer, and how he becomes besotted with Karin, an aspiring model. Their love affair plays out in a way that makes us consider the relationships between sexual desire, money, power, possession, and prostitution.

Instead of the thematic struggle of racial, homophobic and sexist entities, Petra’s setting is seemingly full of upper-class pleasantries: a white all-female cast with a hint of lesbian romance. Staged within Petra, Fassbinder finds an aesthetic that finds itself in identifying the microaggressions inside the bubble, seething with intensity, stirring a tale of possession, fear of abandonment, and ego death at the forefront. In its documenting of the undocumented, Petra remains a cult classic.

9. Pink Flamingos (1972)

Of all the films on the list, John Waters’ Pink Flamingos is certainly the most discussed film among queer communities and theorists. It’s a film that is not regarded for its technical virtues, or because of its narrative. Pink Flamingos became a cult classic because of its view on the politics of disgust and its direct attack on a normative understanding of queerness.

Also, Read – Rafiki [2018] Review: A Gorgeously Shot but Formulaic Queer Drama

After a string of notorious and sensational antics, Babs Johnson (Divine) has settled on the outskirts of Baltimore with her playpen-bound mother Edie, chicken-loving son Crackers, and traveling companion Cotton. Therein begins their secluded debauchery which is challenged when the rich, jealous perverts Connie and Raymond Marble try to usurp Babs’s title of “Filthiest Person Alive,” setting off an escalating series of ever-more-vile antics. Often considered a pioneering work in queer representation, it remains every bit the shocking, offensive, and hilarious film it was during its storied run on the midnight movie circuit, and more as an important work of transgressive art.

10. Je, Tu, Il, Elle (1976)

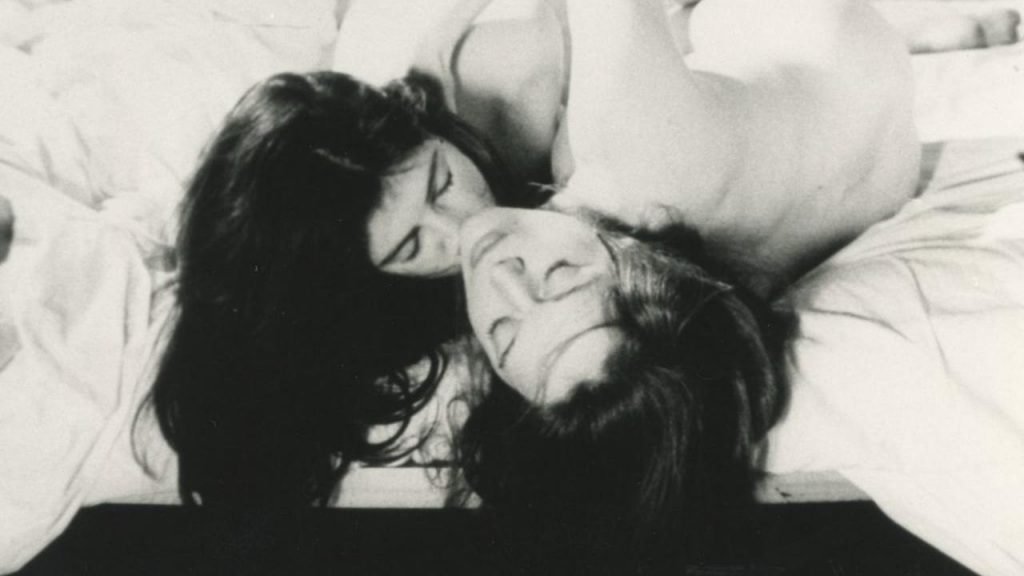

Revolving around a young woman attempting to escape societal convention and control her own life, Chantal Akerman’s Je, tu il, elle is an unsettling experience. Stylized as a three-parted no-narrative, the 86-minute long movie begins as the video diary of a young agoraphobic woman and turns into a road movie. But what remains startling about this is how the Akerman shows desire and passion, and the imagining of it as a whole.

Related to Queer Movies – The Rib [2019]: ‘NYAFF’ Review – An Important Chinese Film

Akerman attempts to depict sex more realistically unlike anything experimented in Cinema at that point, using long takes and static framing as well as dispensing with a background score to mainly focus on the sounds produced by the actors and their environment. It is as raw and real as a wrestling match, as consuming and exhausting as an exercise. It’s sex as an argument. It doesn’t shy away from the clumsiness that can result from braiding naked bodies together. Depicting sex in this way is a choice, radically so, one that has made Je, Tu, Il, Elle such a revolutionary queer film.

11. My Beautiful Laundrette (1985)

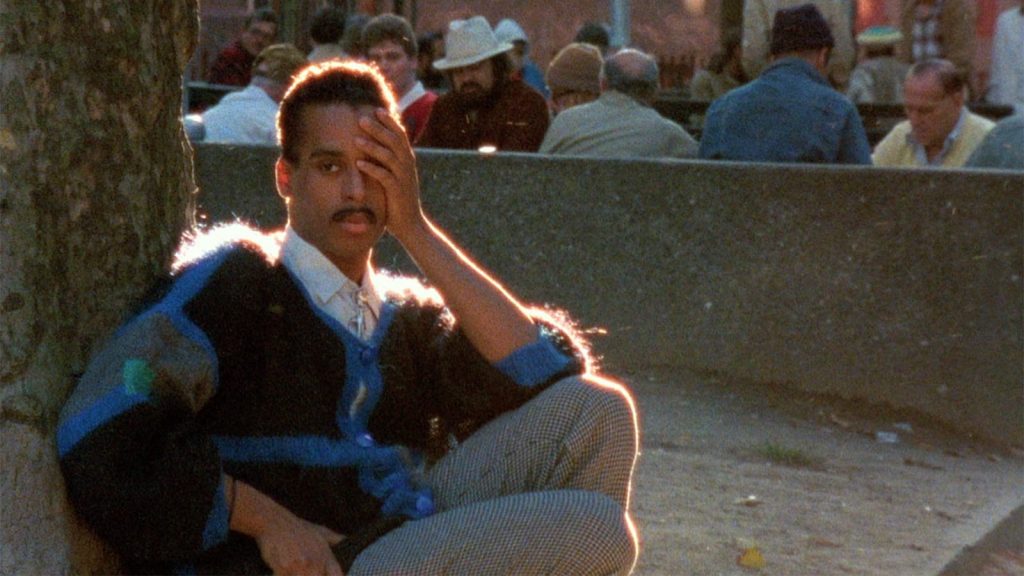

Still, one of the most important films to be made about minority identities, My Beautiful Laundrette is a 1985 British comedy-drama film directed by Stephen Frears from a screenplay by Hanif Kureishi. The core relationship between a white man and brown immigrant broke barriers in mainstream representations of queerness when it came to tackling issues like racism and minority politics.

It revolves around two protagonists, one of them is Omar, played by Gordon Warnecke, is an Anglo-Pakistani in his early 20s. Having dropped out of school, he is jobless and caring for his father, Hussein, who, believing in Omar’s greater potential, sends him to work for his business magnate uncle Nasser. Here the other, Omar’s childhood friend Johnny, played by Day-Lewis, enters the scene soon after; a former skinhead punk, he dredges up the question of identity — Omar has to wonder whether he relates more to the white children he has grown up around or to his Asian relatives.

More Queer Movies – Roobha [2019] ‘LIFF’ Review: A Living, Breathing Agony Of The Societal Trappings

While discussing their business expansion plans, Johnny and Omar naturally, unquestioningly kiss each other, providing a smooth exposition to the fact that the two were and are romantically involved. With these, come in racial tension, the immigrant chain of thought, and a closeted relationship in a Thatcher era. What remains so important here is how queer desire is shown to defer not just interracial resolutions but also does not deny the possibility of intimacy, of something yet to come. As an “impasse,” their queer relationship suggests the potential of coexistence that does not offer reconciliation between the nation and racialized subjects.

12. Maurice (1987)

Set in early 1910s England, this Forster adaptation tells the story of Maurice (James Wilby) and his best friend Clive (Hugh Grant), with the life they attempt to build together in London, which is ultimately destroyed by societal conventions, Maurice’s affair with a country estate gamekeeper, Alec (Rupert Graves), and what they subsequently sacrifice to stay together.

Written and directed by James Ivory, the film – released the year before the introduction of section 28, and into the midst of the Aids crisis – was respectfully received but has never had anything like the popular, Middle England appeal of A Room With a View, Ivory’s other film. A Room with a View was a commercial and critical hit and the winner of three Oscars and five BAFTAs. Maurice, by contrast, lost money at the box office and was nominated for just one Oscar, for costume design.

Similar to Queer Movies – CALL ME BY YOUR NAME [2017] ‘MAMI’ REVIEW: A RIPE CELEBRATION OF FIRST LOVE!

Most certainly this spoke highly about Hollywood that had still not caught up with queer representation in mainstream cinema, and its straightforward approach to male nudity, for instance: though the film is discreet on sex, it does allow the characters the freedom of moving around their bedrooms naked, rather than draped in strategically positioned sheets; it also, crucially, has a happy ending, offering the lovers an escape into love and truth rather than “punishing” them for their sexuality.

13. Tongues Untied (1989)

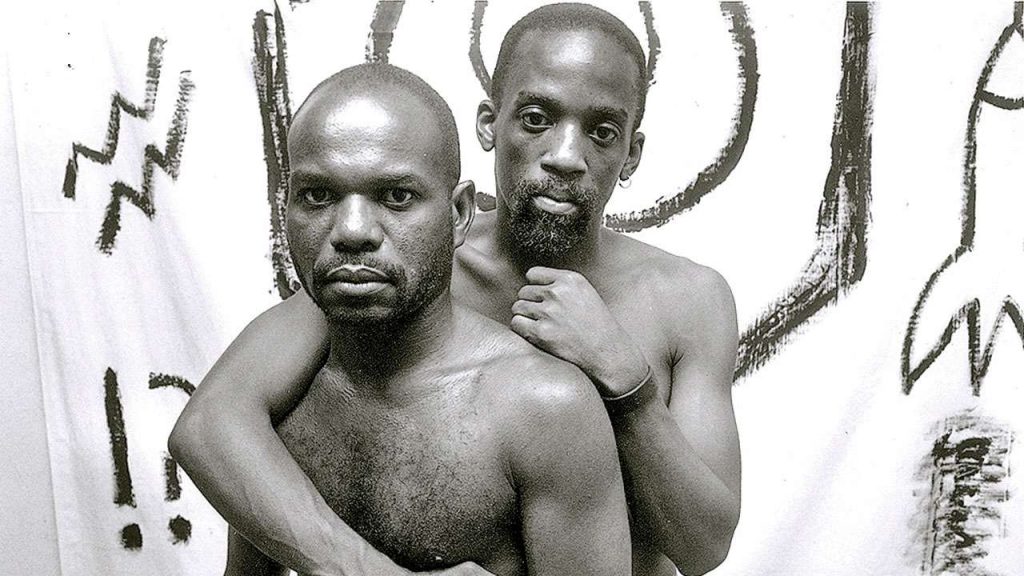

When it comes to seminal queer movies, nothing captures the resistance against sexual and racial tensions with such fervent energy as Marlon Rigg’s Tongues Untied. Released as a collective response from black gay men to the AIDS crisis which ransacked black and gay communities in the 1980s — this documentary furiously confronted institutional and social ‘silence’ around a crisis that threatened black gay men with extinction.

After the sexual revolution of the 1960s shifted the discussion surrounding sexuality from deviance to liberation, the AIDS crisis ushered in a renewed era of moral conservatism under the Thatcher and Reagan administrations in the UK and US. Stunningly shot and edited, with an overlapping, rhythmic soundtrack, Riggs’s self-proclaimed “experimental documentary” fuses elements of dance, poetry, and journalism to fully document the undocumented and silenced.

Related to Queer Movies – Bird Of Dusk [2018] Review: A Crafty and Celebratory Look onto Rituparno’s Reality

Riggs’s film propelled a movement towards a more culturally-specific kind of American independent cinema, though this ultimately seems to have been mostly drowned commercialized cinema of the next decade. Riggs’s film, however, remains uncompromising and ruthless, a powerful jolt to the senses, that refuses to submit before its perceived state of existence.

14. Paris is Burning (1990)

“A film doesn’t change the world,” says Jennie Livingston. “A film can change consciousness. It can be educational.” This is how the director describes her landmark 1990 documentary about the African-American and Latinx drag ball scene in the late 1980s New York City.

Observed through modern eyes, Paris is Burning is remarkable in the introduction of misconceptions and stereotypes that are labeled at the LGBTQ+ community. Key drag terms – “shade”, “realness”, “mother”, “voguing” – are shown and then explained. It presents a portrait of Harlem’s drag ballroom scene – evenings when predominately African American and Hispanic gay men, transgender women, and drag queens would compete against each other in runway battles and vogue dance-offs.

Related to Queer Movies – Loev [2017] – A Tender and Subtly Powerful Gay-Themed Cinema

While drag has been prolific in American queer culture since at least the 20s, for many viewers, Paris is Burning was the first glimpse into the underground subculture of drag. But in retrospect, it has to be remembered that the particular subculture doesn’t exist in the same way anymore. It’s also dated in its representation of queerness. Livingston doesn’t spend time differentiating between transgender women, gay men, and drag queens and the result is a messy generalization of homogeneous identity. But despite being a controversial product of its time, what Paris is Burning still offers is a gateway into a community for which it is considered a vital addition to the legacy of queer cinema.

15. Orlando (1992)

Sally Porter’s adaptation of the Woolf novel tells the story of 16th Century aristocrat Lord Orlando, who is told “do not fade, do not wither, do not grow old” by Queen Elizabeth I. We see Orlando as an aspiring Elizabethan poet and an ambassador for Charles II in Constantinople – before he miraculously switches sex.

As a film, Orlando endures not only for its progressive politics but because of its remarkable reflection on androgynous appearance. Tilda Swinton played the titular protagonist with a magnetic charm, and as a result, Orlando demonstrated that gender-fluid depictions on screen can be artful, gloriously camp, and profitable.

Also, Read: Only Lovers Left Alive [2013]: A Haunting & Hypnotic Mood Piece

Orlando is as much about consciousness as it is about a comment on costumes and gender relations. Potter boldly rejects the prospects of trying to make Swinton seem conventionally masculine, letting the performance transcend gender categories to become a keen meditation on identity politics.

16. The Watermelon Woman (1996)

Cheryl Dunye’s 1996 feature debut follows Cheryl, played by Dunye herself, as she attempts to make a documentary about Faye Richards, better known as the Watermelon Woman: a gay, black 1930s actress whose roles as mammies and housemaids did not do justice to her elusive and complex life. The movie follows her in this process, as Cheryl works in her day job at a video rental store, begins a relationship with a white woman, and learns more about black women’s history—in film, in the gay community, and her native Philadelphia—than she ever anticipated.

Raw and powerful, the film continually interrupts our relationship to history and representation even through the framing of the camera—everything is cast through Dunye’s lens. “I think [the film] lives on for that reason because people still don’t know what a black queer person looks like unless it’s a farcical, drag queeny, commercial way,” said Dunye. “That’s not all that we are. We’re a varied, beautiful ‘rainbow’ of identities.”

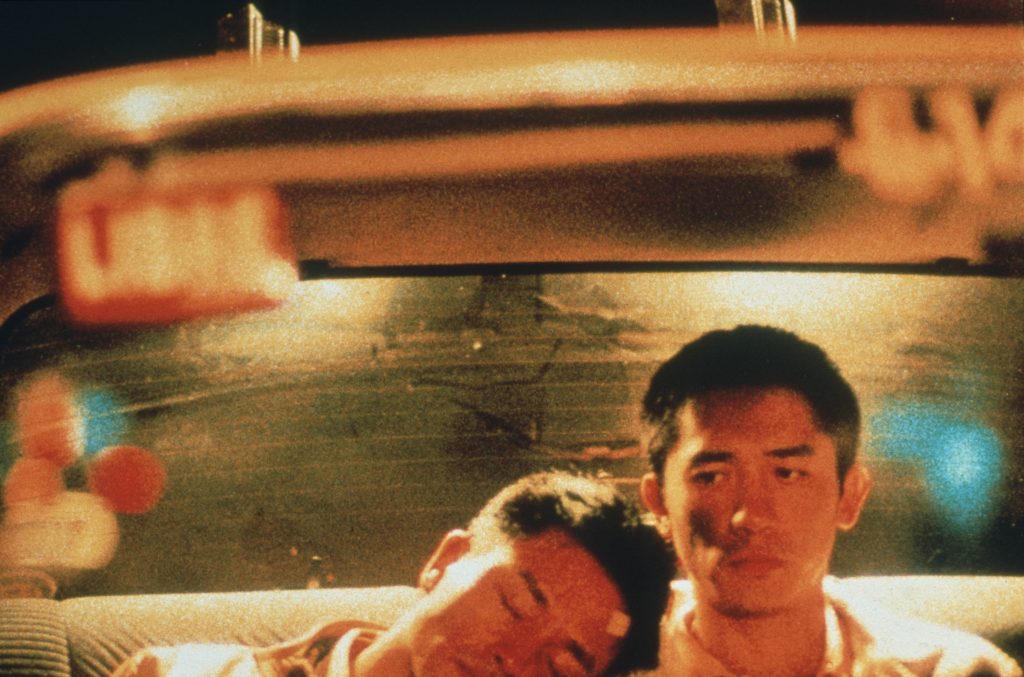

17. Happy Together (1997)

Wong Kar-Wai’s post-modernist tale of two men is an important film not because it shows what it is to fall in love but for what is not shown. It feels like a time capsule, around which the entire force is centered. Throughout the film, the protagonists’ Lai Yiu-Fai (Tony Leung) and Ho Po-Wing (Leslie Cheung) express a constant concern to start over again, to experience a sense of renewal. Happy Together offers this powerful example of the Deleuzian time-image: a world in which the characters drift, unable to complete actions, a cinema unable to provide conventional narrative construction, and instead shows a fragmented world caught up in a perpetual state of melancholia.

Unable to afford the trip back home from Argentina, Lai and Ho are both geographically and psychologically stuck in one place, and they have nowhere to direct their pent-up frustration except at each other. We sense that both parties are privately aghast at the ugly cesspool of jealousy and hostility that their relationship, in reality, has become. But in creating this turbulent and claustrophobic reality, Happy Together vividly embodies the irredeemably hostile environment that indirectly reflects at the perception of queer men.

Related to Queer Movies – Battle of the Sexes [2017] – An Imperfect Yet Rousing & Timely Examination of Rampant Sexism

This film was a milestone for queer and Asian communities, because not only did it showcase a queer Asian couple, but it also discussed the realities of the toxicities within those relationships — no campy cliches, no over-enthusiastic flamboyancy, no tropes. Just two people in love, but not knowing how to be.

18. But I’m a Cheerleader (1999)

Jamie Babbit’s cult comedy about conversion therapy remains one of the most important films of the last century, a film that spearheaded necessary conversations about stigmas, misconceptions about queerness that is an attribute to be cured. The film follows protagonist Megan (Natasha Lyonne) as her family stage an intervention and sends her to True Directions, a camp that promises to ‘rehabilitate’ LGBT teens by converting them to heterosexuality.

What is subversive is the tone- it is not serious as its subject matter but handles it from the understanding of queer standpoint, where the film’s camp humor – essential to its overall style – is established through a script provided by gay screenwriter Brian Wayne Peterson, which pokes fun at heterosexual anxiety and narrow definitions of queer identity.

Related to Queer Movies – 120 BPM (Beats Per Minute) [2017]: ‘IFFI’ Review

The very segregation of gender is heightened by the costume design and art direction- making the campers wear gender-specific clothes, they made to perform a series of tasks associated with each gender. For example, girls are taught how to clean a house, raise a child, how to sew, specifically a wedding dress, how to wear make-up and look like a “pretty young woman”. Guys are taught how to change a tire and fix a car’s engine, how to play football, and how to chop wood and spit.

The idea is if the campers realize and practice their intended role in society then their homosexuality will be cured. The film arrives at the point that idea that performing gender-specific tasks and wearing gender-specific clothes will change who someone loves is just ridiculous and ignorant. But it does so in a stylized, funny, and light-hearted way but still gets the message across that love is love, and it cannot be cured.

19. All About My Mother (1999)

Directed by Almodóvar, who is one of the most internationally successful Spanish filmmakers, Todo Sobre Mi Madre (All About my Mother) is considered an important film to have represented transgender identity breaking stereotypes. It takes place sometime in the 1980s when the HIV and AIDS crisis was at its peak.

First taking place in Madrid, Todo Sobre Mi Madre follows Manuela, a single mother whose son, Esteban, is killed by a car the night of his seventeenth birthday after seeing a play and trying to get an autograph from a famous theatre actress. The rest of the film follows Manuela’s journey to find Esteban’s birthfather in Barcelona, who once went by the name Esteban but is now a transgender woman named Lola, and tell him about the death of his son he never knew about.

Similar to Queer Movies – Pain and Glory [2019] Review: the becoming of Pedro Almodóvar

The defining moment for transgender representation in Todo Sobre Mi Madre is Agrado’s famous monologue she gives to a theatre audience about her journey as a transwoman, where “the aggressive frontality and naked closeness of (the) shot, with Agrado delivering her speech almost directly to the camera and with only her head and shoulders visible against the theatre red curtain. She tells the audience her life story in the form of a lengthy list of the cost of each plastic surgery she’s undergone to attain her female body.

“It costs a lot to be authentic, ma’am. And one can’t be stingy with these things because you are more authentic the more you resemble what you’ve dreamed of being.” It is a statement and a plea, from an individual who assesses the femininity of a cisgender woman, and not the other way around. This is a position trans women are rarely allowed to occupy in their representation in Cinema: she isn’t just comic relief; she also has her interiority and a strong sense of self.

20. Boys Don’t Cry (1999)

“So you’re a boy… now what?” So goes a line spoke about five minutes into Kimberly Pierce’s film about the tragic life of Brandon Teena, Boys Don’t Cry. It’s a clever one, almost a thesis for the rest of the film, which goes on to turn the question over and pick it apart. Partly a coming of age story, Boys Don’t Cry perfectly portrays the exhilaration of falling in with the wrong crowd and falling in love for what feels like the first time. But as a film about the experience of a trans man – real, not fictional, too – the film’s legacy is much more complicated.

Much of the controversy around Boys Don’t Cry happened long after its release. At the time of release, because trans stories were so scarce, the film was mostly considered to be a landmark in trans representation. Trans actors reportedly auditioned for the role of Teena, but in the end, the part went to Swank, who (as far as we know) is straight and cisgender.

Also Similar to Queer Movies – Exploring Black Male Queerness and Notions of Masculinity in Moonlight

Later, she would go on to win an Academy Award for this role. The main argument here is how as a piece of cinema alone, Boys Don’t Cry couldn’t have been better – it is a beautiful and deeply touching film, but as a piece of representation, however, it’s lacking.

![Beneath the Shadow [2020]: ‘NYAFF’ Review – A Slow-Burn Queer Drama That Withers Before Bloom](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/BENEATH-THE-SHADOW-Movie-Review-highonfilms-3-768x512.jpg)