‘In Moonlight, Black Boys Look Blue’: Exploring Black Male Queerness and Notions of Masculinity in Moonlight

Black Cinema, right from its inception – be it the “Blaxploitation” race films of the 70’s or the New Black Cinema of the 80’s – contributed to the excruciating decades of invisibility that queer people experienced on all fronts. When portrayed onscreen on extremely rare occasions, these characters were molded into the cast of racist and homophobic stereotypes, or they simply served as objects of laughter, ridicule and derision. But it was in the early 90’s that the world saw the revolutionary wave of New Queer Cinema, which burst forth into mainstream cinematic culture with tremendously promising potential. Directors like Todd Haynes, Ellen Spiro, and Maria Maggenti, among many others, not only brought a freshness of perspective and a newness of narrative to the screen, but also presented queer sexual identity and politics in a manner which was not only artistic, but also complex, yet nuanced. While groundbreaking films like Looking for Langston (1989), Brother to Brother (2004) and Pariah (2011) have received widespread recognition by audiences and film critics alike, there still persists a paucity of quality black cinema which successfully attempts to locate the origins of the elusive prospect of our personal identities, something which is defined by societal perception and is steeped in intersectionalities and the contortions it creates in the process.

This is where the raw cinematic brilliance of Moonlight comes into play – with eight Oscar nominations and an iconic win for Best Picture, the film paints a heart-rending yet tragically beautiful picture of what it is like to be a black queer man in America, tracing the story of Chiron: a shy and sensitive boy haunted with a kind of pre-world loneliness. The setting is pre-Stonewall America, amongst the crime-ridden streets of Liberty City, Miami; wherein the streets are a witness to the vicious cycle of drug-dealing and poverty the black youth are consumed by, something which goes hand in hand with the coerced exercise of performative strategies of black masculinity every day. The film is structurally divided in the form of a triptych, where each chapter is synonymous with the three phases of Chiron’s life, highlighting the fragility, mutability and complexity of a person’s identity – 9 year old ‘Little’ (Alex Hibbert), who is hounded by bullies for a reason he doesn’t yet fully understand, the teenage Chiron (Ashton Sanders) who battles with his mother’s crack addiction, and experiences an ultimate betrayal from his childhood friend Kevin; and finally, the unrecognizable ‘Black’ (Trevante Rhodes) who hides his true, vulnerable self under layers of performative masculinity. The deliberate use of three different actors demolishes the reductivism of portraying black characters as hyper-masculine and one dimensional: instead, the film fleshes out black, queer characters as dynamic, temporal beings.

Moonlight is successful in juxtaposing different variants of masculinity, some which violently clash with the other, but also others which peacefully co-exist, in an ecosystem of mutual trust and growth. The latter is manifested in the tough, layered and complex masculinity of Juan (Mahershala Ali), who looms over Chiron’s childhood self like a protective father figure; a bond which becomes especially poignant due to Juan’s kindness towards an inexpressively shy and bullied Little, who battles with the absence of his own father and the growing drug abuse of his mother. Juan and his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe) take Little under their wing of affection and acceptance, but Juan is a questionable caregiver, as it is revealed in an ironic reversal that it is he who supplies drugs to Chiron’s mother. But Jenkins deliberately refuses to reduce his characters to one-dimensional entities who identity or define themselves solely through race or sexuality, and invests them with a kind of wholesome integrity which repeatedly leads to the breaking of stereotypes and the undoing of expectations. Perhaps one of the most evocatively tender scenes in Moonlight is when Juan mentors Little through a swimming lesson, which is akin to a metaphorical baptism of sorts; a pivotal “moment of spiritual transcendence”3 between the two characters. The fluid camera movements between Little and his mentor signify a powerful bond, where two souls “in the middle of the world” connect over the notions of self- acceptance and realization, inherent and performed identity:

Juan: At some point, you gotta decide for yourself who you’re going to be. Can’t let nobody make that decision for you.

In The Burden of the Beautiful Beast : Visualization and the Black Male Body (2012), critic Keith M. Harris examines “ the intersection of blackness and masculinity which construct identity categories as a site of racial fetishism and social pathology” (Mask 49). The perpetual presence of a stifling, menacing hetero-patriarchal societal gaze overwhelms and complicates Chiron’s perception of himself, forcing him to confront with labels which he is not yet able to comprehend or grasp in their entirety, resulting in the following heartrending scene :

Little: [innocently] What’s a faggot?

Juan: A faggot is… a word used to make gay people feel bad.

Little: Am I a faggot?

Juan: No. You’re not a faggot. You can be gay, but you don’t have to let

nobody call you a faggot.

A teenage Chiron struggles with a quiet, yet dignified resistance against such labels hurled at him by upholders of erratic, toxic and performative masculinity like the school bully Terrell (Patrick Decile), who ultimately acts as a catalyst to push Chiron towards assuming the same armor of masculinity in the future. George Yancy’s Black Bodies, White Gazes (2008) talks about the gaze black queer men are subjected to by the white community – in this case, by members of Chiron’s own community – a gaze which in itself is “a performance, an intervention, a violent form of marking, labeling, as different, freakish, and animal-like”. Moonlight’s narrative explores the mutual fear and longing of men for one another, often in contexts which are emotionally and sexually charged – Chiron’s only childhood friend Kevin, who calls the former affectionately as ‘Black’, becomes emblematic of a solitary yet transcendentally defining sexual encounter near the ocean, under the moonlight. The title of the play on which the film is based, namely Tarell Alvin McCraney’s unpublished manuscript of In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue, aesthetically and symbolically blossoms onscreen when the two kiss, intertwined in the other’s embrace, as if they are engulfed by a blue-tinted fantasy. But Chiron’s only moment of physical intimacy is hounded by internalized self-doubt, and intimacy for him is liberating and alienating at the same time – he is a boy who forever felt rejected on the basis of his skin color, his sexuality and his sensitivity, and the very sense of his identity hinges on this rejection. When Chiron apologizes for the kiss, we flinch, echoing Kevin’s words : “What have you got to be sorry for?” They exchange a lingered look of tenderness, finding acceptance and recognition in the other.

But what follows is Kevin’s betrayal of Chiron, a betrayal which weighs down oppressively on him and bruises him bloody without and within – the preservation of one’s societal image of heterosexuality and performative masculinity takes precedence over everything their relationship stands for. Such misplaced and distorted images of masculinity and identity have been a part of popular cinema since decades; the representation of black male bodies as purely physical, oozing with threateningly menacing black power and animalistic sexual prowess, especially through damaging narratives in gangsta’ rap. Moonlight exposes the ugly underbelly of such depictions – notions of hypermasculinity does not allow sensitive boys like Chiron to survive by embracing their true selves- let alone entertaining the notion of “coming out of the closet”, which shall only warrant festered wounds, coagulated emotions, and an innate brokenness. We are scared, apprehensive, and hopeful at the same time, when Chiron wordlessly smashes a chair over the bully’s head : it is a momentary, yet powerful catharsis, immediately thwarted by the price Chiron has to pay for retaliation : arrest and subjugation.

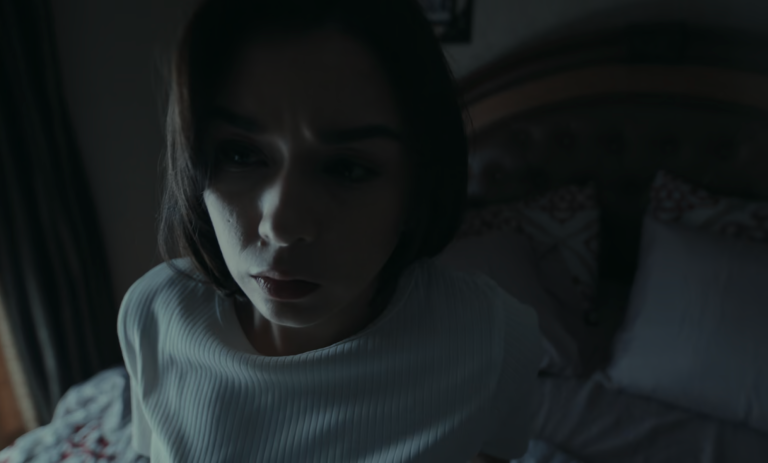

Part III transitions to a an unrecognizable Chiron, who now goes by the name ‘Black’ – his final evolutionary stage is characterized by layers of hard muscles, gangster gold-grills on his teeth and an adoption of traditional masculinity which is connected to a sense of power, control and authority. But deep within, he is still Chiron : we witness Trevante Rhodes’ body sprawled on his bed under the moonlight, curled up in a foetal position, yearning for warmth and intimacy, with Jenkins zooming into his intensely vulnerable eyes which betrays his entire façade in a heartbeat. Chiron is reunited with Kevin after decades, and their electrifying encounter is heartbreaking and uplifting all at once; wherein the latter asks a question which echoes throughout Moonlight :

“Who is you, Chiron?”

As the two of them stare at each other with nostalgia and longing, their thwarted story of love hinges on the redemptive desire to accept and understand the other, where both have been victims of the stifling grip of hetero-normative and performative masculinity within their specific cultures, burying their past selves in a silent, tender embrace, if only momentarily. The final cut shifts to a young Little standing near the shore, bathed in moonlight, beautifully and evocatively blue in its celebration of imagination, acceptance and inter-sectional pride.

Despite its negligible drawbacks, Moonlight has managed to do what queer cinema has rarely done before – while most LGBTQ narratives in America are whitewashed and coded as white, along with the issues of inadequate representation of queer and diverse groups in the reality of the #OscarsSoWhite controversy, Moonlight’s 2017 Oscar win is a significant one. The specificity of queer struggle and identity within the context of blackness, maleness and poverty is the final take away from this empowering art-piece – although mammoth steps are yet to be taken towards the deconstruction of intersectional identity politics, Moonlight bridges the gap between our understanding of the correlation between racial and sexual ideology in American masculinist discourse.

Moonlight Links: IMDb, Wikipedia