William Friedkin’s 1973 horror masterpiece “The Exorcist” was a revelation, not just in grounding horror tropes to something resembling an extreme form of realism but also in recontextualizing the power of faith and unintentionally (or perhaps intentionally) cleaning up the Catholic Church’s brand image. Priests like Father Karras (Jason Miller) are accountable for trauma and existential crises regarding faith. They also possess degrees in psychology, making them a much more welcome addition to the modern world that the 1970s would be ushering in.

But of course, with Friedkin’s “The Exorcist” came its subpar sequels and numerous ripoffs and homages. The trope of a priest managing to exorcise or exile a malevolent spirit out of the body of a young girl became an iconic one that Hollywood would try to emulate. As with all horror movies of repute, the behind-the-scenes drama also caught on to its journey of fame, marketing “The Exorcist” as one of the first cursed films.

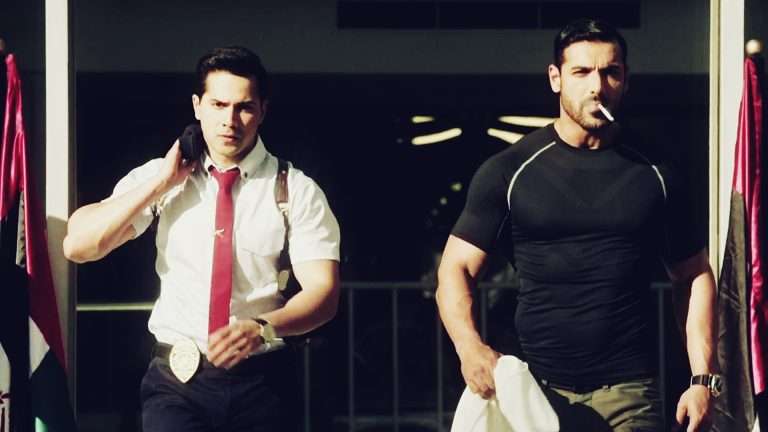

Such a long-winded preamble becomes essential to understanding what “The Exorcism” is trying to accomplish. Directed by Joshua John Miller, the son of actor Jason Miller, it follows washed-out actor Anthony Miller (Russell Crowe), who is cast in a horror film in the role of a Catholic priest as the lead. When Miller begins to exhibit signs of mental deterioration, his estranged daughter Lee (Ryan Simpkins) suspects either the role is becoming too much of a burden for him or something far more sinister and supernatural.

As a meta-movie, “The Exorcism” feels stuck between a rock and a hard place. Emulating the look of Friedkin’s “The Exorcist” in specific scenes and the lighting, especially during the final sequence, its homages do have a personal touch. Crowe’s character feels endowed with a tragedy that references a kernel of reality. His performance in these moments is so defined by his conviction that you are hard-pressed to dislike the movie simply because of his performance.

But that also calls for a massive amount of effort. The enormous context of emulating “The Exorcist,” as well as including scenes showing freak accidents in the movie sets that had always been thought of as a supernatural response, with the movie almost reinforcing that sentiment as part of that narrative, feels too much like an inside baseball attempt for horror die-hards. For casual moviegoers having no idea of “The Exorcist” or horror canon in general (yes, they exist), the true test of this movie becomes its standalone nature. And from that standpoint, “The Exorcism” fails.

It comes across as a confused film, unable to choose between an exploration of the aftermath of trauma as well as alcoholism and how it affects an already broken family or a pulp fare about exorcism, which climaxes with a ten-minute sequence of Crowe as Miller loudly chanting and screaming as the camera shakes and convulses with him while trying to capture the possessed priest. The narrative almost breaks credulity after the action preceding it had started to strain it. It also doesn’t help that while Ryan Simpkins, as Miller’s daughter Lee, is decent in her role, her subplot truly adds nothing to the movie. There are inconsistencies with the quality of filmmaking as well.

The opening sequence shot like a one-take following an actor practicing his lines while entering a house, which slowly reveals itself as a film set, is an impressive sequence. However, in contrast, some scenes in the dark are so poorly lit that it becomes nigh impossible to discern where the scene is progressing or where the characters are situated, and the inconsistency becomes glaring. You couple that with the overly produced-sounding jump scare, and again, this is a film that feels strangely sandwiched between dramatic fare and disposable trash. The inconsistent acting amongst the rest of the supporting cast doesn’t help either.

Unlike the other movie of last year, also starring Russell Crowe as an official exorcist for the papacy, “The Exorcism” lacks the pulpy feel or sheer camp that would have elevated it out of its portentousness. It cannot exist as something singular without the context weighing it down and almost burying it. For people familiar with “The Exorcist” or the numerous homages to horror movies, this has some bright spots, as well as Crowe’s sincere performance. But what Joshua John Miller’s film required was an identity of its own, away from the shadow of the film and the genre it is emulating and homaging so hard.

![Coded Bias [2020] Netflix Review: Fighting Racism splattered over Technology](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Coded-Bias-1-highonfilms-768x432.jpg)

![Assassins [2020] Review – The Strange and Captivating True Story of a Political Killing](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Assassins-2020-768x432.jpg)