Kazuhiko Hasegawa’s The Man Who Stole the Sun (Taiyo wo nusunda otoko, 1979) is riddled with the anarchic spirit of the Japanese New Wave that it would evoke divisive reactions from its viewers. Some might love it for its unclassifiable nature: mixing black comedy, slapstick elements, and Hollywood-ish tropes. Some might like it in parts, finding it hard to grapple with its unevenness and drawn-out cinematic moments. And of course, some might absolutely hate it. Let’s not forget that those who love The Man Who Stole the Sun also love the way Hasegawa and his co-writer Leonard Schrader weaves an unabashed dark comedy out of nuclear terrorism. It possesses a tightrope walking sort of narrative scenario, where its oft-kilter humor could have been mistaken as an utterly desensitized portrayal of terrorism, particularly considering the political scenario in Japan during the 1970s. In fact, it was perceived like that only, just how Dr. Strange Love (1964) was condemned for its funny premise revolving around nuclear war.

Political activist Kazuhiko Hasegawa directed only two movies, The Man Who Stole the Sun being his second and last. It was said that his mother was pregnant with him and living in Hiroshima when the atom bomb was dropped there [1]. Screenwriter Leonard Schrader lived in Japan for many years. He has also collaborated with his brother Paul Schrader on the scripts of Blue Collar (1978) and Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985). Moreover, many critics draw comparisons with the nihilistic tendencies of Paul’s iconic creation Travis Bickle (Taxi Driver) and the central character of The Man Who Stole the Sun.

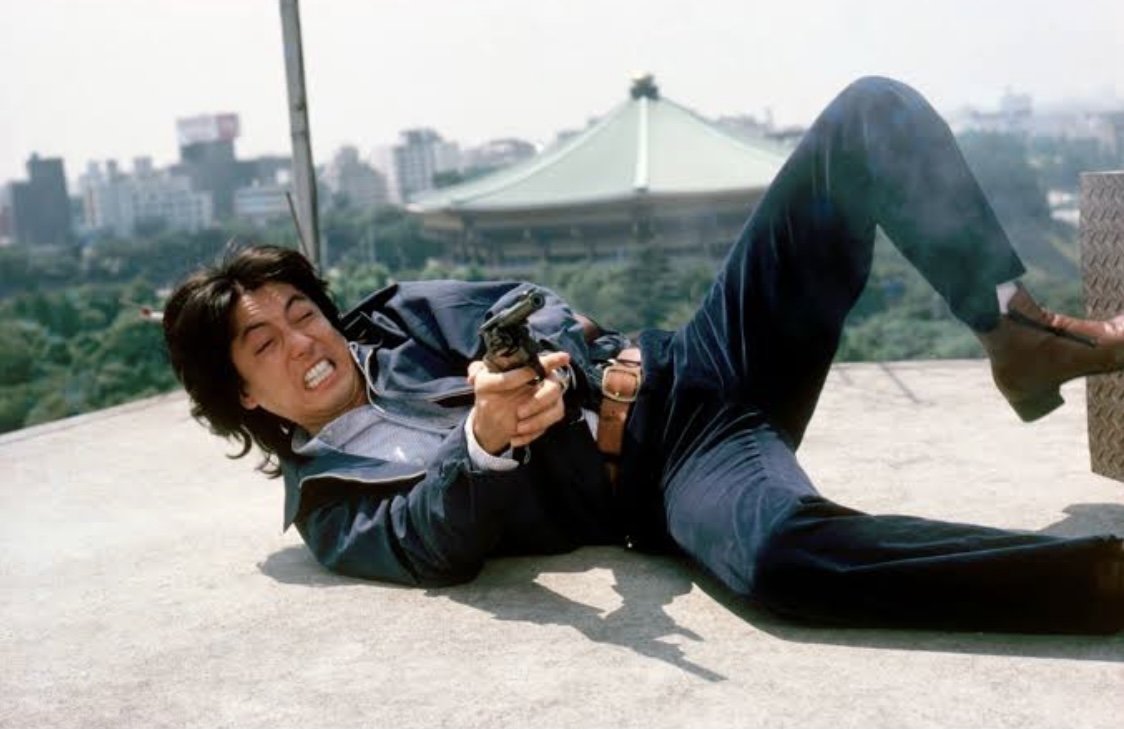

That aside, Hasegawa perfectly sets up the on-screen narrative clash by the choice of actors to play his two chief characters. Kenji Sawada who plays the alienated high-school teacher Makato Kido is a pop star, known as the ‘Japanese David Bowie’. Bunta Sugawara plays middle-aged Detective Yamashita, who belongs to the earlier World War II generation with a clear-cut sense of right and wrong. Bunta Sugawara ascended to iconic actor status for playing hard-boiled yakuza in Kinji Fukasaku’s epic The Yakuza Papers movie series. The clash of their ideals – or to be more precise, the lack of any ideals in Sawada’s Kido – causes the boiling point which is one of Hasegawa’s foremost preoccupations.

Related to The Man Who Stole the Sun – 10 Distressing Films on the Potential Aftermaths of a Nuclear Holocaust

Hasegawa’s The Man Who Stole the Sun is lauded for ‘breaking taboos in a nation still traumatized by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings’ [2]. That too through a highly satirical treatment. Makoto Kido is a long-haired, gum-chewing, sun-glass-wearing high school science teacher. It is made clear that instead of sticking to high school text, Kido is teaching his students about the atom bombs and nuclear energy. When he isn’t teaching about those things, he simply sleeps in the class. He is quirky too, either crazily running the obstacle courses or screaming from rope swings during the recess. The students generally find Kido boring and call him, ‘bubblegum’. Their perspective somewhat changes when the school bus during a field trip is hijacked by a lunatic at gunpoint (Yunosuke Ito). The tough detective Yamashita and Kido do their best to save the students from the hostage situation. Both are honored as heroes in the newspapers. Both share a mutual respect for each other, but Kido feels he has found the perfect foe to carry out his quest.

Earlier in the narrative, we see that Kido has converted his one-room apartment into a laboratory. Now it becomes clear that what he is trying to build is a homemade nuke. Of course, to build one, Plutonium (Pu-239) is essential. This leads to a wackily stylized sequence, where Kido breaks into a high-security government facility to steal enough fissionable material. Using freeze frames and stop motion, the action sequence is designed like an old video game (the sound effects are actually taken from a video game called ‘Space Invaders’), as Kido escapes from the facility by using flamethrowers and handmade bombs. Having got his hands on the radioactive material, Kido spends his days making the bomb, painstakingly clearing each obstacle course to make one. In fact, he makes two; one very real, whereas the other has a certain level of radioactive material to show up on a Geiger counter but technically not a bomb.

The sequence where Kido builds the bomb looks very detailed. Nevertheless, it seems some of the bomb-making footage was cut due to the directive issued by the Japanese authorities [3]. Furthermore, after the slapstick confrontation with guards at the government facility, the poker-faced Kido mentions to his students that it’s impossible to break into such facilities. This ‘what if’ scenario immediately comes across as frightening when Kido cleverly discards the dud one at Diet building (Japanese Parliament) lavatory and calls the authorities through a voice scrambler. There’s enough evidence for the authorities to believe that the threat of a homemade nuke is authentic. Since Kido isn’t motivated by something decidedly political, his demands are as absurd as the demands that are cultivated in a consumerist society.

Kido strongly emphasizes that detective Yamashita is the only man he will talk to regarding his demands. He smartly cuts the telephone call with the detective before it could be traced. In his first one-minute plus call with the detective, Kido however, doesn’t have an idea what to ask for. He simply asks for the televised baseball games to be telecasted all the way through, instead of cutting it at a crucial point of the innings for news. He is delighted when the demand is met. Nevertheless, Kido doesn’t know what to ask for after that.

In their first call, Kido smugly asks Yamashita to call him ‘nine’, i.e., now he is the 9th owner of a nuclear weapon (after the 8 nuclear weapons tested nation-states). In his apartment, Kido affixes the flags of the 8 nations on the floor and places his portable nuke among them. He nudges it like a football, and even hugs it to sleep. The deeper allegorical treatment related to Kido being the 9th owner of a nuke gains more traction in the later parts of the narrative.

The absurdity of the situation gradually escalates when Kido’s path crosses with a young, spirited radio DJ, ‘Zero’ Sawai (Kimeko Ikigami). Kido calls her on a show and mentions his possession. Though she dismisses it as a prank, Zero dubs him ‘Mr. A-Bomb’, and talks about the coolest thing he could ask, for example, a Rolling Stones concert. When Zero learns through industry insiders that the Foreign Ministry is trying to arrange for a Rolling Stones concert, she is fascinated by ‘Mr. A-Bomb’. Soon, she even meets the stranger whom she believes to be ‘nine’. Rejecting Yamashita’s command to aid him, Zero messily entangles herself with Kido. By this time, Kido comes fully under the corruptible influence of absolute power. His next demand is 500 million yen. The decay is physical too as Kido is slowly dying of radiation poisoning.

Black comedies are fine tools to deal with certain morbid aspects of our society. The outlandishness or absurdity can nonetheless make us more aware of the perils and sadness of things. In fact, on an individual level at times we do laugh at the worst things in our lives. The Man Who Stole the Sun from a narrow perspective could be read as a narrative about the aimlessness of a crazed loner, seeking connection or validation, in a Japan which has already reached the zenith of its economic miracle. This gives us the temptation to classify it as a cat-and-mouse thriller; or as mentioned above a battle of wits between an establishmentarian and a disaffected prankster. But Hasegawa’s narrative clearly doesn’t fit the mold of an action thriller despite the no-holds-barred Hollywood-style chase.

Also Read: United Red Army [2007] Review – An Exactingly Detailed Account of Revolutionary Zeal Gone Wrong

Hasegawa and Schrader’s handling of the tone does come across as a bit flawed (or maybe I need re-watches to adjust myself to it) and mildly confirms certain narrative conventions: for instance, the one-dimensional characterization of the naïve, anti-establishment radio DJ. Furthermore, the media satire aspect of the narrative didn’t seem to work as much as its satirical takes on the establishment. But what I wholeheartedly admire is how Hasegawa uses the over-the-top elements to deliver an unbelievably deeper as well as funny commentary on the era of nuclear power. The sheer unpredictability of the third act plus the ambiguous ending allows room for bigger, thoughtful interpretations, freed from the immediate narrative premise.

I can also understand if someone hated those portions, decrying the freewheeling, illogical features of it. Still, in a roundabout way, Kazuhiko Hasegawa’s The Man Who Stole the Sun intriguingly makes us laugh at a nightmarish ‘what if’ scenario. We laugh not just thinking about the senseless schemes of Makoto Kido, but also laugh wondering about the ridiculous posture of nuke-owning nation-states. Well, what else can we do?

★★★★

Trailer

Notes:

- Kaiju Shakedown: The Man Who Stole the Sun, Grady Hendrix, Film Comment, July 2015

- Cinematic Terror: A Global History of Terrorism on Film, Tony Shaw, Bloomsbury Academic

- The Midnight Eye Guide to Japanese Film, Tom Mes, Stone Bridge Press

![The Day After I’m Gone [2019] MUBI Review – A Father-Daughter Relationship Drama that Investigates Grief and Mental Illness](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/The_Day_After_Im_Gone_HOF1-768x322.jpg)