Almost a century has passed since Chaplin’s cult classic “Modern Times” (1936) saw the light of the day, but it seems that the laborers’ spatial position in an advanced capitalist country has scarcely improved. Stephen Maing (director of “Crime+Punishment”) and Brett Story’s (director of “The Hottest August”) 2024 documentary “Union” stand as a testament to this fact. Made over three years, the film tracks the Amazon Labor Union (ALU) movement from its nascent stage until it made New York’s Staten Island’s JFK8 warehouse the first unionized Amazon workplace.

“Union” opens with a scene where Amazon workers languidly board a bus that takes them to the warehouse, reminding us of the opening scene of “Modern Times”, where the workers, in a flurry, run toward the factories to get exploited – both physically and of course economically. The initial scene of “Union” – drenched in a poignant blue – allures us to draw an analogy with “Modern Times” by comparing the images of the Amazon workers’ facial expressions with those of early twentieth-century laborers shown in the Chaplin classic to decipher that how the longue durée capitalist exploitation has metamorphosed, over a century, the early morning factory-going workers’ faces from anxious to sullen and at times hapless.

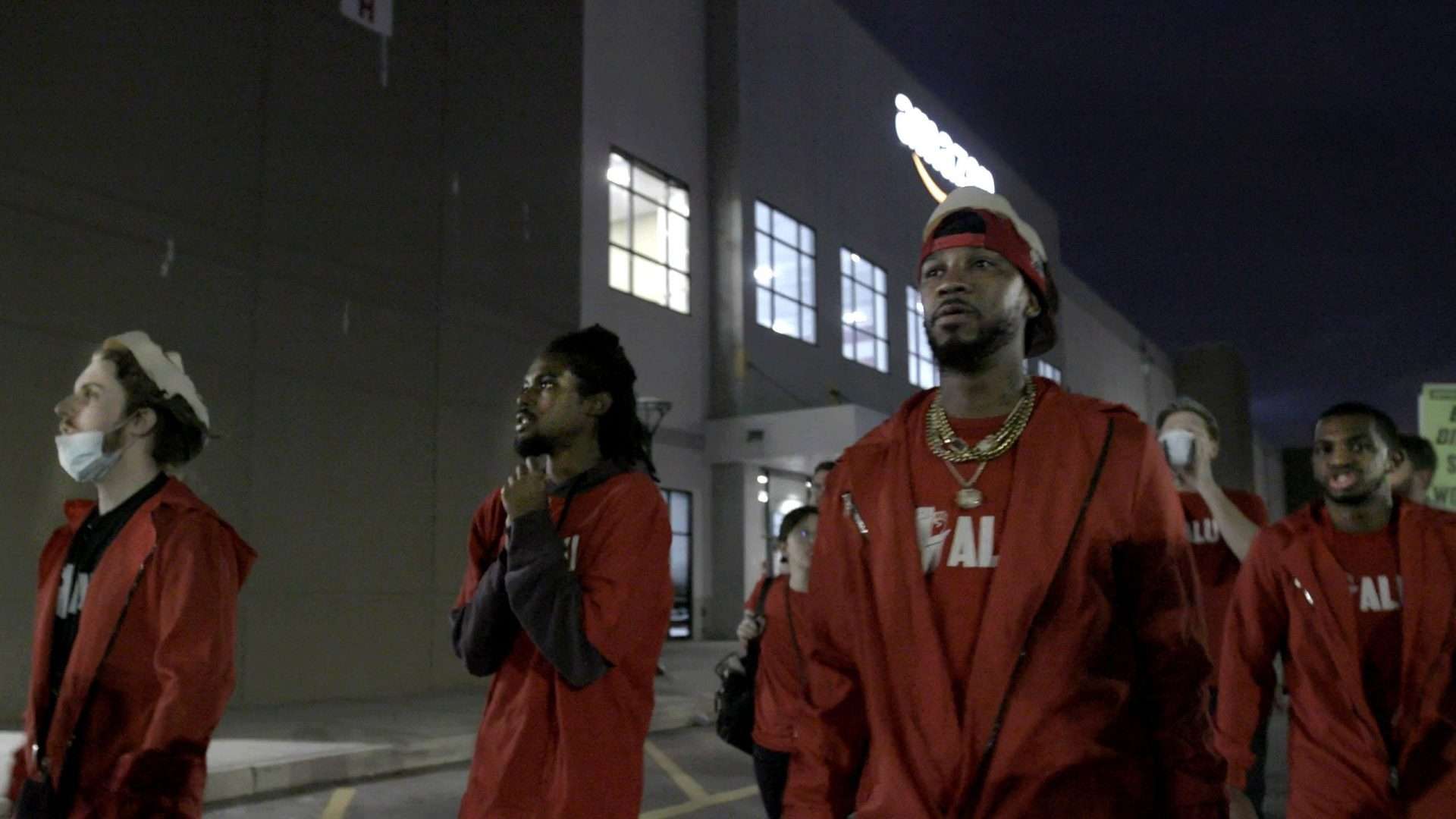

From the very beginning, “Union” makes it clear by tacking the footage of Jeff Bezos’s eleven minutes long space travel in his Blue Origin’s New Shepherd Rocket ship with the shots portraying Chris Smalls and his comrades’ efforts to organize the unorganized workers of Amazon during the desolate spring nights, that the film is going to take the side of the working class. In this particular context, it might be important to paraphrase one of the remarks Chris Smalls made on Jeff Bezos’s space travel.

Smalls, who became the face of ALU during its struggle to collect the consent of the two-third majority of Amazon workers to organize a vote, jibed by saying: “Let billionaires like Bezos have fun sightseeing in the cosmos — it gives the rest of us a golden opportunity to reshape the Earth in their absence.” The bulk of the film deals with this opportunity where Smalls, Connor, and other ALU organizers make history by establishing a union in the JFK8 warehouse.

“Union” is not a conventional talking-head documentary; rather, it is a keenly observational digital portraiture of a movement that could be considered the most important labor movement of the twenty-first century. Martin DiCicco’s camera, occasionally assisted by Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe’s melancholic soundscape, revolves around Chris Smalls’ every effort to organize the workers in a contemplative manner but, without any intention to push Smalls to the foreground as a protagonist. And in this way, “Union” eludes the canonical labor cinema.

Smalls was fired from the warehouse during the epidemic when he organized a protest in demand of sufficient protective gear. By the time the film opens, in the spring of 2021, Smalls has already started getting media attention. The film relentlessly documents Smalls’ organizing stratagems, ranging from his usual Zoom meetings to devising strategies to counter Amazon’s anti-union campaigns.

Amazon spent 4.2 million dollars on union-busting campaigns in 2021, and another 14.2 million dollars in 2022. These campaigns include mandatory “captive-audience” meetings where the company discourages its employees from joining unions. In one such meeting recorded covertly by Natalie (an Amazon employee), shown in the film, through her shaky mobile camera, we can see a coordinator addressing the audience: “We’re asking you to do three simple things: get the facts, ask questions and vote no to the union.” These multiple clandestine hand-held shots delineate Amazon’s efforts to instill an anti-union spirit in the workers’ psyche by propagating that ALU has no track records, they don’t guarantee anything and to no extent they can represent Amazon workers better than the company itself.

What makes “Union” such an important film in the history of labor cinema is its efforts to unravel the polemics hidden in the crevices of a labor organization by delving deep into the subject. It does not shy away from foregrounding the ALU organizers’ struggle against the gender, race et al. issues inside their organization. For instance, in one scene, Natalie pushes back the suggestion made by some organizers, that Chris intentionally gets himself arrested to draw some attention that would help their unionization drive. Natalie argues by saying that, a black guy getting arrested by the New York police can end up losing his life. In another scene, Natalie – who by then had left ALU – expresses her dissatisfaction by saying that almost everywhere all the time, the unions are dominated by male organizers.

Union’s propensity to juxtapose aesthetics and honesty reminds us that the political can also be beautiful or artful. The integrity with which the film has been made is a story in itself. As Chris Smalls revealed a few snippets from his lived experiences with the crew members, they won the hearts of the audience at various festivals and screenings. For example, there is a scene in the film, where in the dead of night a storm destabilizes ALU’s tent and the camera person hurries to help Chris. Later Chris admits in an interview: “Thankfully, our camera crew understood the difficulties we had to go through as Amazon workers and what we were trying to achieve. We were fortunate to have that relationship where if they had to drop the camera to help us in an emergency, they absolutely would’ve done that.”

On the other hand, the crew also made it clear that, like conventional documentaries, they had no interest in trying to erase their presence from the film in order to meet the aesthetic ends. Stephen Maing (one of the makers of “Union”) said in an interview: “We exist adjacently without altering the direction of their work, but also without pretending that our presence doesn’t matter. A lot of trust, care, and compassion were at the heart of our relationships. We think of each other as friends now in an odd way, having gone down this journey with these shared, similar goals.”

In the United States of America, there are less than 6% unions in the private sector and less than 10% in the public sector. ALU’s struggle, in such an advanced capitalist country has just begun. In the time of war, genocides, and imperialism, Stephen Maing & Brett Story’s “Union” sets an example of resistance. It also contributes to the psyche of every human being on the planet, who is partaking in any kind of resistance movement, by foregrounding that this movement is a Black-led multi-racial movement.

To conclude, I quote Brett Story: “We subtly included issues of class, race, and gender difference because those permeate our lives and affect our ability to organize. It’s also important that you see that it’s a Black-led, multiracial struggle. The future of labor organizing has to be broad-tent and requires that we learn how to work together across these cleavages that are disorganizing in our everyday lives.”

![Dangal [2016] : An Entertaining Sport Film](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/dangal1-768x392.jpg)

![Lady Macbeth [2017]: Pugh is the Star of Victorian Tragedy](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Lady-Macbeth-film-768x322.jpg)

![Annihilation [2018] – An Ultimately Disappointing Take on a Bewitching Sci-Fi Premise](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/natalie-portman-stars-in-annihilation-768x383.png)

![Until We Meet Again [2022] Review – A bizarre, wafer-thin ghost story](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Until-We-Meet-Again-1-768x324.jpg)