“When people find out that I am trans, they think that I transitioned to become something else, but I transitioned to stop living a lie. I transitioned so I could live in the truth.”

– Laverne Cox.

“Sometimes it takes a friend to drag you out of hell and into the light.”

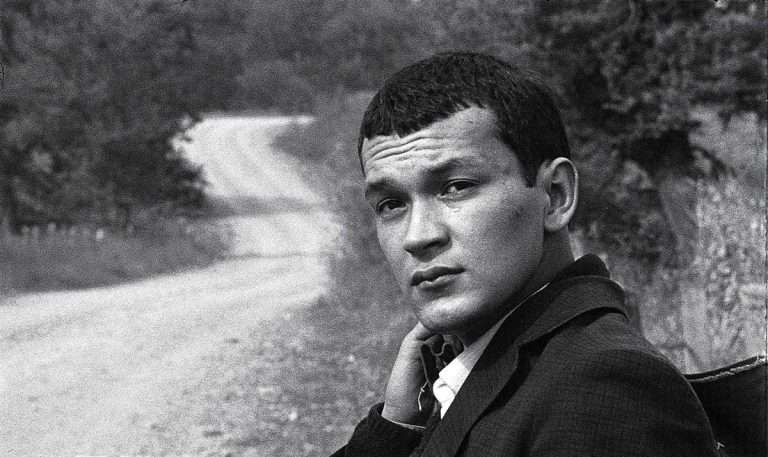

– Sean Baker, director of Tangerine.

In the heart of Los Angeles, where the glitz and glamour often overshadow the stark realities of those living on the margins, Sean Baker’s “Tangerine” (2016) bursts onto the screen with a raw, unfiltered depiction of life for transgender sex workers. Shot entirely on iPhones, the film’s vibrant and frenetic style mirrors the chaotic lives of its protagonists, Sin-Dee Rella and Alexandra, as they navigate a world that is both hostile and indifferent to their existence. At its core, “Tangerine” is a story about friendship, resilience, and the relentless pursuit of identity in a world that often refuses to acknowledge it.

The film opens with a scene that sets the tone for the entire narrative: Sin-Dee, freshly out of jail, learns from her best friend, Alexandra, that her boyfriend and manager, Chester, has been unfaithful. What follows is a wild, day-long odyssey across the streets of Los Angeles as Sin-Dee sets out to find Chester and the woman he’s been cheating with. While driven by a simple plot of betrayal and revenge, this journey unfolds into a complex exploration of the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality.

One of the most striking aspects of “Tangerine” is its unflinching portrayal of the transgender experience. The film does not shy away from the harsh realities faced by transgender individuals, particularly transgender women of color. In one scene, Alexandra performs at a bar, singing her heart out to a nearly empty room. Her performance is a poignant reminder of the loneliness and isolation that often accompany the pursuit of one’s dreams in a society that marginalizes and ostracizes. This scene echoes the sentiments of many queer theorists who argue that visibility and representation are crucial yet fraught with challenges. As Judith Butler states, “Gender is not something that one is, it is something one does, an act… a doing rather than a being.” Alexandra’s performance is not just a display of talent but a defiant act of self-assertion in a world that constantly seeks to question her identity.

The film’s narrative is also deeply rooted in the concept of a chosen family. Sin-Dee and Alexandra’s friendship is the emotional backbone of the story, providing them with the support and understanding that their biological families often fail to offer. This theme resonates with Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality, which highlights how overlapping systems of oppression impact individuals differently. For Sin-Dee and Alexandra, their intersecting identities as transgender women, sex workers, and people of color compound their struggles, but their bond helps them navigate these challenges. Crenshaw’s assertion that “where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects” is vividly illustrated in the way the characters support each other through the intersecting oppressions they face.

Moreover, “Tangerine” highlights the resilience and agency of its characters. Sin-Dee and Alexandra are not portrayed as victims; they are active agents in their own lives, making decisions, pursuing goals, and fighting for their dignity. This portrayal aligns with queer theorist Michel Foucault’s idea of power as something that is exercised rather than possessed. The characters in “Tangerine” navigate a web of power relations, asserting their identities and carving out spaces of agency even within oppressive structures. The film also touches on the theme of visibility and invisibility. The transgender community, particularly transgender women of color, is often made to exist on the fringes by the cis-gendered society, their lives rendered invisible by ‘mainstream’ narratives. “Tangerine” brings these lives into sharp focus, demanding that audiences see and acknowledge their struggles and humanity. This visibility is a powerful act of resistance against transphobic ideas of erasure and marginalization.

Furthermore, “Tangerine” delves into the use of comedy as a tool to present the seriousness of the issues it tackles. Comedy is not merely a distraction from the harsh realities but a vital tool for survival. The film’s humor, often sharp and biting, serves as both a coping mechanism for the characters and a vehicle for social commentary. Sin-Dee’s fierce determination and fiery personality are frequently expressed through witty banter and comedic exchanges, which lighten the narrative and underscore the absurdity of the discrimination and hardships they face.

In one memorable scene, Sin-Dee confronts Chester and Dinah, the woman he has been cheating with, in a laundromat. The ensuing confrontation is laced with humor, as Sin-Dee’s rapid-fire insults and Dinah’s incredulous responses turn a moment of betrayal into a farcical spectacle. This comedic approach does not diminish the seriousness of Sin-Dee’s pain but rather highlights her strength and resilience. The use of comedy aligns with the tradition of using humor to address serious subjects, a technique that allows audiences to engage with difficult topics in a more accessible manner.

By infusing the narrative with humor, “Tangerine” highlights the resilience and strength of its characters, showing that even in the face of adversity, they retain their humanity and spirit. By laughing in the face of adversity, the characters assert their dignity and refuse to be reduced to their suffering. This aligns with queer theorist Judith Halberstam’s assertion in The Queer Art of Failure that humor can be a form of resistance and a way to “poke holes in the toxic positivity of contemporary life.”

Sean Baker’s decision to shoot “Tangerine” on iPhones is more than a stylistic choice; it is a deliberate statement about accessibility and innovation in storytelling. This technical marvel democratizes filmmaking, suggesting that powerful stories can be told with limited resources. The use of iPhones enabled Baker and his team to capture the vibrant, bustling energy of Los Angeles in an intimate and immediate way. The resulting footage is dynamic and engaging, drawing viewers into the fast-paced world of its characters. Tangerine’s kinetic energy and vibrant color palette reflect the vibrancy of its characters, who refuse to be rendered invisible by their circumstances. This approach aligns with the principles of queer cinema, which often seeks to disrupt traditional narratives and aesthetics to offer alternative perspectives.

In conclusion, “Tangerine” is a vivid and compelling exploration of identity, resilience, and friendship in the face of intersecting oppressions. Through its raw and unfiltered lens, the film captures the complexities and challenges of transgender lives, particularly for those living on the margins. By highlighting the themes of chosen family, the use of comedy to address serious issues, and the performative nature of gender, “Tangerine” offers a nuanced and multifaceted portrayal that challenges viewers to reconsider their perceptions of identity and resilience. Despite its critiques, the film’s authentic representation and innovative storytelling mark it as a significant work in queer cinema. As audiences reflect on the vibrant lives and indomitable spirits of Sin-Dee and Alexandra, they are reminded of the ongoing fight for visibility, recognition, and the right to live authentically.