Martin Scorsese isn’t particularly known for his surrealism. The legendary director is mostly associated with guns, gangsters, anti-heroes, unreliable narrators, Italian American families, and Catholicism. All wrapped up inside slow-motion, freeze frames, and curse words. A few of these trademarks fold into the surrealist genre (such as anti-heroic protagonists and unreliable narration), but generally speaking, Scorsese opts for sensical cinematic prose that follows a chain of cause-and-effect rather than surreal dialect. The type of prose where everything is methodical and motivated—by greed (“The Wolf of Wall Street“), compulsion (“The Aviator”), or jealousy (“Raging Bull”)—if a little mad. Then, there’s “After Hours,” which blows a little mad out of the water in exchange for all-out insanity.

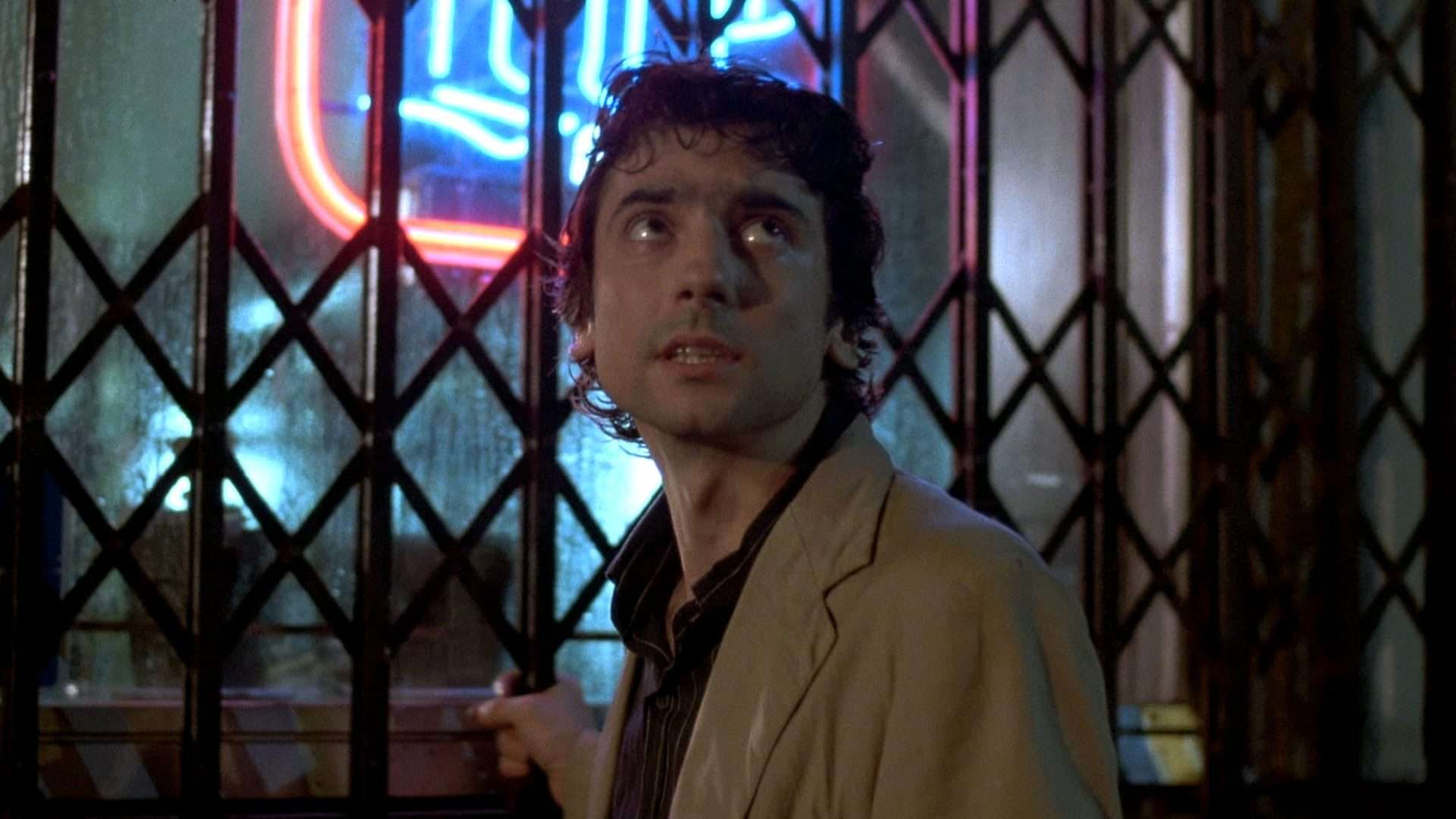

Relatively unknown by mainstream audiences, “After Hours” has been excavated like a treasure chest by cinephiles, praising and prying apart the cult comedy ever since its release in 1985. Cult comedy, black comedy, absurdist comedy, satirical comedy, melodramatic comedy—anything that isn’t bolt and nails, all-American crowd-pleasing laughs. Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne) carries the nonsense of “After Hours” on his nice guy shoulders—or at least, not a bad guy. Just some guy. Some naïve, data entry yuppie who lives alone in New York City—Scorsese’s sweetheart setting.

Paul begins the film as a bored bachelor and ends a harried, traumatized soldier of the night, strolling into work in yesterday’s clothing, covered in plaster dust, looking as if he’s just tried to break into the McCallister house from “Home Alone” (a star of which also appears in “After Hours”— Catherine O’Hara). How he ends up in such a state is humorously preposterous, the whole film unraveling over one infernal, never-ending night uptown.

Paul traverses desolate urban spaces—New York after hours—that are street lamp-lit and emptied out, besides the Mohawks-only club night. “After Hours” feels like Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks painting come to life—Nighthawks (something Paul isn’t, by nature, concerned about leaving his apartment past 11 pm), with a Kafkaesque spin. Paul ties off another tedious weekday by chatting with Marcy (Rosanna Arquette) at a café, who gives him her phone number under the pretense that her roommate sells plaster-of-Paris paperweights. Part aroused, part reluctant, Paul, the unlucky everyman, calls Marcy behind the thinly veiled facade of needing a bagel-shaped paperweight at midnight.

So far, so normal. But when Paul takes a cab to Marcy’s place, it’s as if he’s ridden straight into an absurdist parallel universe—like the Ghost of Christmas Past cabbie in “Scrooged” that runs red lights into Bill Murray’s memories. Losing his twenty-dollar bill out the car window is the first domino to trigger an outbreak of bad luck, evil omens, and opportunistic characters that haunt Paul after closing hours until the ending credits.

It’s not a literal alternate reality that Paul enters, but something metaphorically akin to it. He walks through a revolving door of Marcy’s mood swings and blows her off with a dramatic rant over her insufficient pot, then meets her sculptor roomie Kiki making a paper mâché of a man screaming, Edvard Munch style (an overt reference to the film’s surrealist undertones). Unable to afford the subway home, Paul goes to a bar where the waitress practically falls in love with him, and the owner informs him of the local burglaries. A few deaths, seductions, punks, and a mob later, Paul finds himself inside the paper mâché man Kiki foreshadowed, being carted off by thieves in the back of a van and tumbling out in front of his work building at daybreak.

If the world Paul returns to in the morning signifies the “real” world, then perhaps New York “after hours” is the unreal—a nightmarish other ruled by dream logic and dislocation. The House of Hades for the mythologically literate, or The Upside Down from “Stranger Things” for the pop audience. Paul scrabbles and limps his way through the narrative like a drunk man fumbling with his keys in the dark, and keys are, in fact, a small but potent symbol in the first act of “After Hours” as if unlocking the gates to this purgatory underworld that Paul willingly—if unconsciously—opens.

“After Hours” is a film built on coincidence and frustration—sexual, existential, career, contextual (which we’ll get onto in a second), or simply the frustration of trying to get home across town without enough change. It’s not entirely removed from reality like a Luis Buñuel picture is, but just enough to make you feel uncomfortable. Unsettled. After all, no one questions the illogic of a dream if they know they’re only dreaming, but to find yourself in an uncanny, not-quite-probable reality is far more disconcerting.

“After Hours” couldn’t have existed outside of the modern age of paranoia, which began in the mid-20th century. The 40s Red Scare, the mass side effects of ’60s psychedelics, and the ’80s Satanic Panic were just some climatic pin-points of the paranoia pot boiling over, palpable in the contextual aura of “After Hours.” There is a feverish, desperate quiddity to Paul’s agonizing Hero’s Journey home, where even dialing a number is like pulling teeth when ice-cream woman Gail (O’Hara) is piping out random numbers to distract him.

This makes “After Hours” a penny in the slot machine of “yuppie nightmare cycle” movies that fleetingly circulated cinema during the Age of Reagan. “Blue Velvet,” “Into the Night,” “Miracle Mile,” “Naked,” “Desperately Seeking Susan”—they’re all conjoined by their (usually male) middle-class white protagonists getting hoisted into unfamiliar, threatening worlds. A screwball-noir crossover genre that “After Hours” defined.

Scorsese’s fingerprints can be found all over “After Hours,” not just because he physically had his fingers on the camera but because his career anxieties were clearly being funneled into the only mode of expression he knows how to use: film. The narrative’s suspicious, fighting-against-the-current feel echoes Scorsese’s own battle against getting his passion project, “The Last Temptation of Christ,” into theatres.

A focused amplification of the religious motifs woven throughout his filmography (later expanded with “Silence”), “The Last Temptation of Christ” was to star Willem Dafoe as the Son of God wrestling with his human form, surrounded by enticing sins. The fattening budget of his fictionalized Bible epic had Paramount biting their nails, unsure, until they eventually backed out and stymied the whole project.

Disheartened, Scorsese moved onto the comparatively quick, low budget, and easy production (as easy a film production can be, anyway) of “After Hours,” the script to which he’d acquired through a “Mean Streets” actress written by Joseph Minion. He related to Paul’s uphill journey against circumstance, admitting in a 2022 interview, “I actually kind of identified with the character at that point. Just lost in the underworld.” The House of Hades. The Upside Down. New York after hours.

Wrapped up in thirty consecutive night shoots, Scorsese made a radical stand against the commercialization of cinema—who deemed “The Last Temptation of Christ” too risky—by making “After Hours.” At the same time, he put his flopping career worries (imagine!) to rest, hitting two birds with one stone. Scorsese was then able to return to his personal “Heart of Darkness” production about Jesus and Mary Magdalene, narrowly avoiding a Coppola-esque nervous breakdown through the strenuous shoot in Morocco. “The Last Temptation of Christ” was finally released in 1988.

“After Hours” gets off a fairly normal foot before Paul takes the keys—which nearly smack him to death on the head as the second domino in the bad omen layout—to Marcey’s apartment. Having accepted the movie’s challenge, he’s plunged into the unrelenting pace of films like “Uncut Gems,” “Beau is Afraid,” “Good Time,” “Cloverfield,” or even the merciless and increasingly bizarre string of obstacles in “The Hangover.” For Paul, it’s the dull wash of a TV set or the electric shock adrenaline of being chased by the mob, and little in between.

Thematically, Scorsese incorporates subtle references to castration—to “breaking the whole thing off”—in conjunction with a general feeling of emasculation. Perhaps this is linked to his suffocated feelings about his filmmaking career at the time. The hot-cold women Paul encounters repudiate him and make up the bulk of things, turning his late-night shot at getting lucky into a living hell. Women chase him down the street and encase him inside a paper mâché sculpture, where he’s almost left to die if Scorsese hadn’t changed the original ending. You might be fooled into thinking it all relates to some grand sensical conclusions, thanks to the recurring symbols such as the lost bank-note appearing in Kiki’s paper mâché. However, the circular symbols are just that—circular. Linked, but going nowhere.

Scorsese makes a fool of anyone trying too hard to find meaning in “After Hours.” The film raises points and questions on masculinity (and mythology, author Michael Rabiger argues) but is more concerned with screwball comedy for the sake of screwing with you, with asking questions without any intention of answering them. Although surrealism is constructed upon anti-authoritarian desires to explore new avenues of human consciousness, pushing against the conservative bourgeois grain—in short, to stick it to the man—it’s still fundamentally meaningless.

That’s the whole pointless point of it: to contradict, confuse, meander, and lead the spectator to dead ends or endless roads, to invite them into a maze and then ditch them there just for kicks. And being a surrealist film at its core, “After Hours” does just that, with the maze being the deserted streets of downtown New York on a weekday.

The film’s surrealist cover art speaks of what’s to come, with Paul’s head pinched between two oversized, manicured, hand-of-God fingers, his neck screwed onto an alarm clock in a classical surrealist homage. It could feasibly be a painting by René Magritte, and if you imagine what lies beyond the poster borders, melting clocks wouldn’t come as a shock. Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory replicates that of a limbo dreamworld, and like most absurdist movies, it’s the fear of no one listening or understanding you that makes dreamscapes so terrifyingly lonely, like a labyrinth you can’t find your way out of. A yuppie nightmare cycle.

If you read “After Hours” through the lens of purgatory, Scorsese’s Catholic signature can still be found, invisible beneath the surface as stars are beneath the clouds. He’s also present in the baffling 1980s New York setting, which we cruise through in an alternate version of Travis Bickle’s Yellow Taxi. The setting is studded with Scorsese’s famous tracking shots and features a flawed but relatable protagonist on the brink of a nervous breakdown.

As usual, Scorsese breaks the rule that the camera must be unnoticeable. Instead, he dictates the rhythm of the movie through the camerawork, like a puppeteer holding the strings, demanding our attention, deciding how fast we go, what we slow down to see, what we rush to keep up with, what we feel. “After Hours” was a speedy, economical project that could have felt rushed, cheap, and clanky were it not in the hands of a master, who tightened the bolts and polished the script better than the shiny black FBI shoes loathed by acid test heads.

The first draft of the script left Paul in his paper cast to die, but instead, Scorsese had him return to work the next morning, sleep-deprived and straight-faced from shock. Even when he makes it out of the yuppie nightmare, he makes it to work, not home (arguably, the office is the home of the yuppie, but not one they likely enjoy). It’s an unsatiated conclusion for Paul, withheld from full catharsis and knocking the heels of his red slippers only to be transported back to the same tedious workday he was trying to shake off in the first place.

Of course, he does get a little relief compared to the original finale, which suffocated both character and audience completely and took some of the comedy out of the comedy. The absurdist nature of “After Hours” may not draw any finite conclusions, but perhaps one inference could be that there is no catharsis for the modern man, that he’s lost to an unnatural concrete world of paranoia and disconnection.

You need some fortitude, open-mindedness, and observational skills to watch “After Hours,” but it’s definitely worth it. The (intentionally) irritating ticking clock soundtrack you can’t unhear is another feature that makes “After Hours” so engrossing. Then there’s the irksome score building up, steadying out, and never fully going away with its out-of-sync noises, awakening the anxiety of our limbic system. The moody noir lighting, dynamic camera movements, eccentric characters, and sinuous plot—on the same road, but constantly bending—just keep piling onto the pros list for watching “After Hours,” making you wonder how it’s rarely mentioned amid the everpresent Martin Scorsese buzz.

![Polytechnique [2009]: A Ponderous Glimpse into the Layers of Misogyny](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Polytechnique-film-images-a77103a9-e80f-4b1b-9733-442e828f3f9-768x432.jpg)

![Miss Sloane [2016]: An Aaron Sorkin Imitation](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Miss-Sloane-768x512.jpg)