“I think the best way to retire is to die.” This was, in part, the response a 77-year-old Claire Denis gave in 2024 when asked whether her one-two punch of “Both Sides of the Blade” and “Stars at Noon” two years prior would mark the end of a legendary career immortalized by the nonverbal language of human bodies moving listlessly through destitute spaces. By this time, Denis was already in the process of proving her vitality by prepping “The Fence,” yet another examination of the neocolonial powers that have defined her oeuvre from the very beginning.

It’s not a theme Denis directly tackles in every one of her films, but colonial oppression certainly looms like a shadow forming in the corner of the room, just waiting to be aired out by the sunlight peering through an open window. With “The Fence,” the windows are wide open, but the sun is gone and the gates remain firmly shut; as with all of Denis’s Africa-bound pressure-cooker features, nobody’s going anywhere.

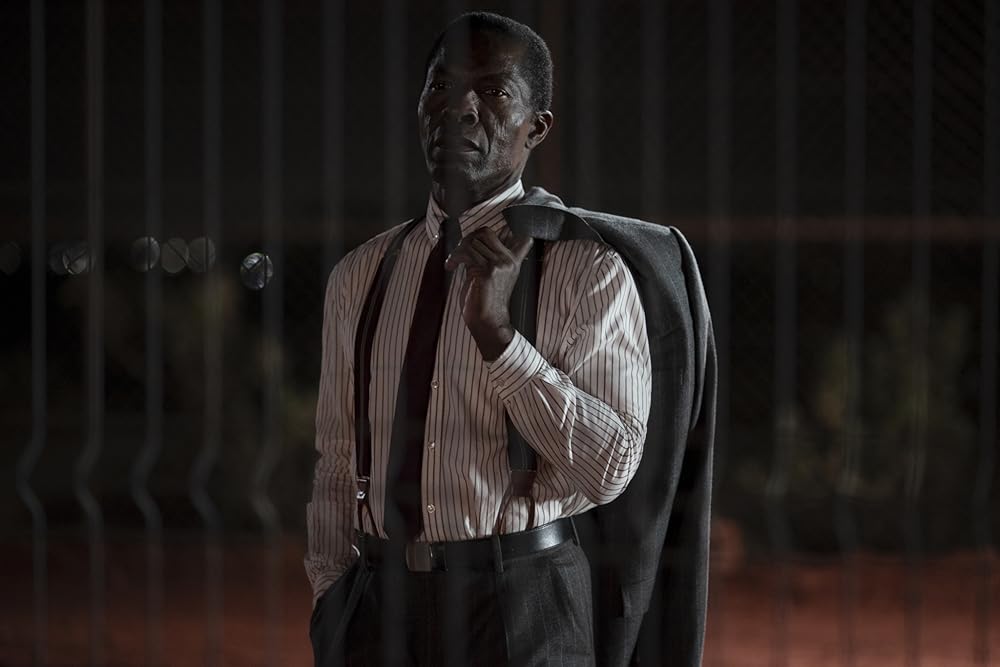

This reality slowly becomes apparent to Horn (a gruff and unshaven Matt Dillon), a construction site foreman left to deal with the blowback of a mysterious workplace accident. Somewhere in Western Africa (this is literally as close to a precise location as “The Fence” is willing to provide), the site in question is cordoned off and crewed by armed guards; this doesn’t stop Alboury (reliable Denis regular Isaach de Bankolé) from appearing out of the dark in a suit, politely demanding to be given the body of the worker—his brother—so that the family may properly mourn.

Horn isn’t willing to relent on what he claims to be protocol, not least of all because this is the night his young bride Leone (“How to Have Sex” breakout Mia McKenna-Bruce) is set to come in from London. Alboury, though, refuses to back away, and the resulting tension proves too much for all within the fence’s borders to handle.

It’s clear from the very first moments of “The Fence” that something is slightly off-balance—not necessarily with regards to the character dynamics that feed the resulting suspense, but rather in the film’s assembly. Scenes aren’t given quite as much space to breathe as Denis typically offers, and her camera subsequently appears somewhat more reticent than usual to linger on those bodies with its usual spectral gaze.

It’s a worrisome omen for a film whose containment feels less predicated on curating sinister pressure and more on adhering to its stage play origins. Bernard-Marie Kortès’s source play was unveiled all the way back in the late ‘70s, but its interest in culpability and guilt in an abusive colonial milieu still resonates now, which would explain why Denis found this material so alluring in the first place; it’s in this respect that “The Fence,” after a wonky opening, begins to find its footing in the dust.

Much of this effect comes from the steadily increasing focus on Horn’s number two Cal (Tom Blyth), whose direct involvement with this situation proves to be an anvil slowly pressing against his neck. Blyth’s resultant mercurial demeanor is nothing short of entrancing, and it’s enough to awaken even Dillon’s surprisingly stilted presence when shit hits the fan and fists hit faces. McKenna-Bruce, meanwhile, is tasked with a more underwritten role, but her outsider’s perspective proves a valuable addition in maintaining the privileged isolation that makes Alboury’s task so much more personally felt by comparison.

Almost akin to a direct atom-split that turns Isabelle Huppert’s protagonist in “White Material” into two separate characters, the dichotomy between Leone’s lingerie-laden wandering through the compound and Horn’s more direct complicity constitutes the most direct conduit for the audience to find whatever discomforting revelations may be abound on both sides of “The Fence.” Claire Denis, by that metric, isn’t bringing much to the table that she hasn’t brought more vigorously in the past, but her most recent soft-reset finds its own muted power in this stifling sense of inertia, whether it be intentional or otherwise.

![Thirst [2009]: Fairy tale of Love and Bloodlust](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Thirst-Films-2009-768x347.jpg)

![Directions [2017]: ‘TIFF’ Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/directions_01-768x384.jpg)

![Leviathan [2014]: A scathing Political satire reflecting on Human Suffering](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/leviathan-highonfilms-768x432.jpg)

![Legendary in Action! [2022]: ‘NYAFF’ Review – A Patchy Homage to Hong Kong Wuxia Films](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Legendary-in-Action-768x512.jpg)

![Séance on a Wet Afternoon [1964] Review– A Visually Entrancing and Superbly Written Character Study](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Seance-on-a-Wet-Afternoon-1964-768x432.jpg)