With the dawn of synchronized sound in Hollywood in 1927, music became an active participant in the filmmaking process. Rhythm and structure were no longer only elements of the screenplay but could also permeate the audience’s subconscious through the use of sound. However, the arrival of New Hollywood cinema in the 1960s turned film scoring from merely being an accessory to an integral part of a filmmaker’s style and content.

As directors in New Hollywood gained more control over the creative process, they ensured that one relationship remained constant: the composer. Therefore, the impact of these solidified director-composer collaborations allowed film scoring to enter different parts of the production process, contributing to the auteurism movement by unifying sound and visuals at a deeper level.

Before exploring how modern director-composer partnerships challenged the use and integration of film music to define form, it is essential to understand how scores informed function. Revision, in the postproduction phase, was the score’s primary responsibility in Old Hollywood cinema. To illustrate this concept, take the musicals of Fred Astaire and their production processes. Fred Astaire would dance along to his songs’ music, often in his ballet shoes so as not to distort the sound in editing. Then, as the film was being edited, the composer would adjust the melody to the respective cuts, which were not always in time with the composition they had initially.

In the process, the composer could alter Fred Astaire’s performance, the pacing of the sequence, and ultimately, the rhythm of the story. Hence, film scoring in Old Hollywood was already tampering with other elements of a film rather than just engaging the audience. Although this manipulation was more reactive than proactive. Neither directors nor composers had the agency to make music a central narrative or thematic force. This would all change in 1960 when Bernard Hermann decided his music would be an extension of a knife on-screen in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho.”

Thoughtful Read: Hitchcock and His Emotional Minefield

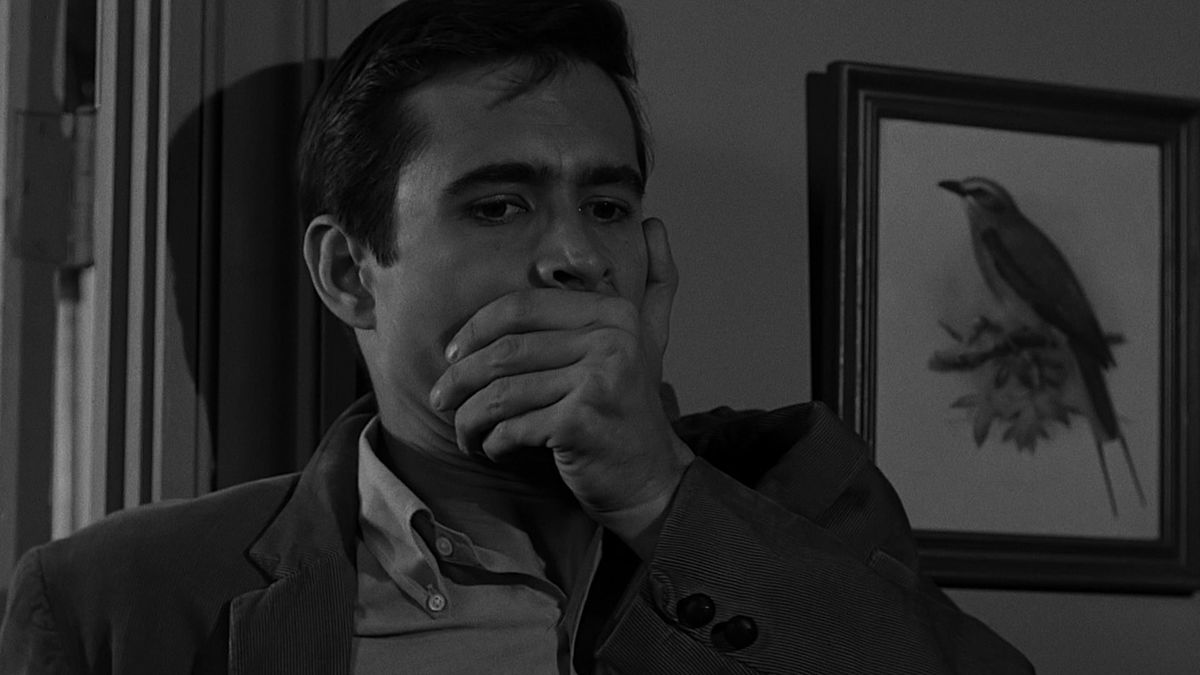

Both known for their authoritarianism, Alfred Hitchcock and Bernard Hermann became New Hollywood’s first and most formidable director-composer duo. They first met in the post-production of “To Catch a Thief” in 1955, and they developed a personal connection during the production of “The Trouble with Harry” in the same year. Hermann and Hitchcock bonded over their strict demands and staunch artistic vision, making Hermann’s music the perfect extension of Hitchcock’s complicated psyche. It was their collaboration on “Psycho” where Hitchcock not only relinquished his control over the film but also gave Hermann unprecedented creative freedom.

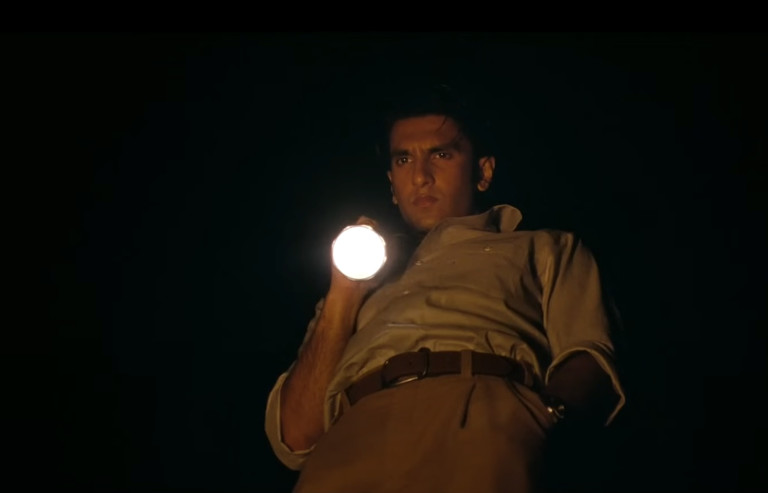

In one of the pinnacle moments of New Hollywood, the score, still in post-production, was no longer just an amendment but rather acted as its savior. Hitchcock was about to send the film to television, but after he heard what Hermann did with the shower scene, which was against Hitchcock’s instructions in the first place, he realized that he had to give it a theatrical release. In the infamous shower scene, Hermann’s score became a stand-in for violence and terror, but more importantly, it stylized Norman Bates’s tool for murder. The sharp, piercing sounds of the strings interpret Bates’s stabs as a reflection of his insanity and transgression.

It flawlessly blends the psycho-sexual content of the film with Hitchcock’s artistry as a director, as it meets his quick cuts, invasive close-ups, and eerie production design. The presence of this jarring score also heightens the power of the silences that follow. It creates a perverse sense of unease as the audience watches a dead body lying in the bathtub – a still grotesque image that is made more favorable because it lacks Hermann’s agonizing strings. Hitchcock’s silences, known for pushing the boundaries of conventional sound theory, were no longer isolated. In “Psycho,” Hermann complemented this trademark by making them something that audiences now anxiously waited for by adding even more unsettling music.

“Psycho” showed upcoming Hollywood filmmakers that the score is a reinforcement of style, and the relationship between a composer and a director could be so ubiquitous that it permeates how a film is made. After Hitchcock and Hermann laid the foundation for how artistically lucrative a director-composer duo could be, many filmmakers in the years to come searched for their partners in crime. One of the most notable and enduring collaborations is that of Steven Spielberg and John Williams.

Spielberg, the son of a classical pianist and a student of film music himself, first worked with Williams on “The Sugarland Express” in 1974. Williams agreed to work with him because he said, “[Spielberg] seemed to know more about film music than [he] did.” Their most iconic and monumental work would come the following year in the first summer blockbuster, “Jaws.” A score very much inspired by Hermann’s in “Psycho” because of the isolation of a few musical notes, Spielberg thought Williams was “pulling his leg” when he first played it for him.

Similar to the score’s role in “Psycho,” the music described an even more integral part of the story: character. The shark in “Jaws” is an antagonist that the audience barely sees but always feels. In the opening scene of the film, Chrissie, an unsuspecting teenage girl, goes skinny-dipping in the ocean, and once the camera is seemingly placed underwater, two of the most iconic notes of New Hollywood cinema enter quietly. These notes, ranging in volume and sonic location, characterize the looming threat in the entire film. What makes it the antagonist, however, is how it combines with Spielberg’s visual precision.

When the camera takes the point of view of the shark underwater, there is no use of diegetic sound – it is entirely Williams’ score. When the perspective shifts to the outside of the water – that of the residents of Amity Island – diegetic sound enters the soundscape. Spielberg creates this distinction to signify territory: a technique he would use in later films like “Jurassic Park,” which switches the position of the score.

Therefore, Williams’ foreboding, ominous score for “Jaws” not only identifies the character but also gives Spielberg the proper ammunition to manipulate audience expectations. Though the film was still in post-production, “Jaws” signaled a turning point, with its score not merely reinforcing style but actively shaping it. With the Spielberg-Williams collaborations, the director-composer relationship evolves again by becoming a pervasive audience expectation, where it becomes difficult to recognize them as two separate artists.

The relationship between diegetic and non-diegetic sound is manipulated by Spielberg, but the filmmaker who completely subverts the hierarchy is David Lynch. Lynch uses ambient noise and room tone as his primary sonic force, many times overpowering dialogue, narratively coherent sound effects, and even music.

Hence, Lynch had to find a composer who was skilled and enthusiastic enough to have the difficult role of providing film music that had to traverse not just seditious sound design but also the subconscious of Lynch himself. Angelo Badalamenti came from the world of popular music, and he met Lynch on the set of “Blue Velvet” in 1986 as Isabella Rossellini’s voice coach. Lynch was so impressed with Badalamenti’s work with Julee Cruise for the film’s original song, “Mysteries of Love,” that he subsequently asked him to score the whole film.

All of this happened during production, as it was too risky for Lynch to keep the score dormant until post-production, when the film could be something else entirely. Thus, Badalamenti and Lynch frequently discussed the music on set, with Lynch often urging him to join in his transcendental meditation. Their most notable collaboration is on the television show “Twin Peaks,” but the effect of Badalamenti’s consulting in the production phase can be seen – and heard – in the follow-up film, “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me,” where the score became the co-director.

In “Fire Walk with Me,” Laura Palmer and Donna Hayward accompany two men to a night club, dubbed “The Pink Room,” and what follows is classic Lynch: a surrealistic, erotic, and ultimately, tragic dance sequence. Like the production of the show, Badalamenti was pulled into the production of this film, and he wrote “The Pink Room” so that Lynch could play it while he filmed.

This had a profound impact on two of the most memorable elements of the scene: Sheryl Lee’s (Laura Palmer) performance and the lighting. The addition of strobe lighting acts as an echo of the constant percussive beats, creating a jarring effect both consciously, which is conveyed on the visual level, and subconsciously, which is conveyed on the musical level.

Must Check Out: All David Lynch Movies, Ranked

Having the score in production allowed Lynch to complete his aesthetic by mangling the explicit and implicit. Sheryl Lee replicates this effect by moving her hips in time to the chords of the guitar but maintaining a blank expression. As she is dancing, her head falls back as the music picks up in tempo. All of these subtle movements communicate mental dissonance and decay: a necessary cue for Laura Palmer’s descent in the film.

These two elements exemplify that Lynch could have only communicated mood and character visually with the presence of the music. The score provided context, and for a filmmaker like Lynch, that is exactly what he needs to make his abstract ideas understandable to the cast and crew. Thus, film music extended far beyond specific narrative components and became a language that those making the film can all understand. Lynch and Badalamenti, capitalizing on the score’s profound effect on production, make the terms “director” and “composer” almost synonymous.

It was arguably the 21st century’s most influential director–composer duo, Christopher Nolan and Hans Zimmer, who made “composer” all but synonymous with “writer.” Not only has their relationship produced film-scoring techniques that have become commonplace today, but it is also partially responsible for both of them achieving elite status in Hollywood. Zimmer made a name for himself as a master of the synthesizer, and his approach to film scoring was a direct result of the digital age because he constantly experimented with new technology.

Nolan first met Zimmer for “Batman Begins,” where Nolan had a similar experience to Spielberg when Williams first played the two notes for “Jaws.” Nolan said, “When Hans first played the two notes he had in mind for the main theme, it scared the shit out of me.” However, that became the very thing that fit the high-concept films that Nolan made and what Nolan appreciated about Zimmer: his ability to use minimalism in a maximalist way. Zimmer’s revolutionary way of scoring prompted Nolan to reverse-engineer and introduce the music even before the final script was finished.

Nolan did just that in perhaps their richest collaboration, “Interstellar.” Zimmer was not even aware that it was a science-fiction film; he received a short story from Nolan that enumerated his feelings on parenthood and an obscure conversation he had with his family. Nolan had not even finished the script yet because he wanted to go back into it from the music, and when Zimmer played what he came up with the next day, based only on Nolan’s little note, he decided to fully commit to making the film.

The score’s impact on “Interstellar” must be analyzed on a fundamental story basis, as it informed much of the screenplay. Therefore, it is essential to isolate the summit of any story: the climax, which in the case of “Interstellar,” is the “Tesseract” scene. Many still take issue with how “conveniently” it resolves the intricate plot of the film, packing in exposition into a short amount of time with a distraught, loud Matthew McConaughey delivering his lines, and Zimmer’s organ score making them unintelligible. The score is the key to unlocking why this climax ultimately works and why it even has a right to be there in the first place.

In summary, Matthew McConaughey’s character discovers that he was the “ghost” that his daughter was seeing at the beginning of the film, and he communicates with her through anomalies in gravity. The scientific details do not matter so much as the reason why they work. The film makes it clear that love is the one force that transcends time and space, and the origin of that concept is the score. As Matthew McConaughey wails and calls out to his daughter, Zimmer’s two piano notes that are later accompanied by church organs remind the audience that the story hinges on love being another universal force like gravity.

The climax’s validity lies in its faith in the power of love—a power that would not exist in the film without Zimmer’s score, which Nolan used as the foundation for shaping the script. “Interstellar” is not a story extended by its music, nor an auteurist expression embellished by a composer; it is a film generated from the score itself, a rarity in the landscape of New Hollywood. In doing so, Zimmer and Nolan—alongside other director-composer partnerships following similar paths—turned this creative relationship into an artistic statement in its own right.

Director-composer collaborations are so common in New Hollywood cinema that they have become one of the first things upcoming filmmakers seek. With only two films, Barry Jenkins already found his musical counterpart in Nicholas Britell, and with a mere one feature, Lee Isaac Chung, director of “Minari,” stated that he intends to work with Emile Mosseri for the rest of his career. As film scoring trickled down from post-production to even before pre-production, it reflects New Hollywood cinema’s most discernible movement: auteurism.

Though what started as the increased agency for directors has broadened to include composers. The director-composer collaboration is the most influential in defining New Hollywood auteurism because it approaches filmmaking from the medium’s unique quality: the harmony of sound and image. Correspondingly, the role music plays in film has drastically morphed from simple emotional accompaniment to being the central part of the structural integrity of a film.

However, more than auteurism, the most significant consequence of these collaborations is blurring the line between diegetic and non-diegetic sound. When the diegesis itself is intrinsically linked to the score, as is evidenced by numerous New Hollywood cinema director-composer duos, it is nonsensical to call that same score non-diegetic.

From both the cinematic and narratological perspectives, film music is no longer one or the other, nor is it in a liminal space between the two. Instead, director-composer duos have made film scores so ingrained in style and content that those terms simply do not apply. This makes cinema the most immersive it has ever been because the audience, and even at times, the cast and crew, are unaware of where the film begins and where reality ends.