This December marks a year since the passing of Shyam Benegal, a great filmmaker whose storied career saw him move across India, making stories centered around everyone from the Telangana peasant to the Hyderabadi nautch girls to the Goan expatriates to men who sought to free their nations, be it India or Bangladesh. Unlike the other great Indian auteurs whose work was dominated by their own creativity, Benegal’s best came out of collaborations with the other greats of Indian cinema.

One unlikely combination that produced what many would consider Benegal’s best was his brief sojourn with Shashi Kapoor, who too breathed his last on a December day nearly a decade ago. These two individuals, deeply committed to art, deeply in love with India even when their efforts found better appreciation abroad, were at their finest in a bold adaptation of India’s greatest epic.

The central status of the Mahabharata in the canon of Indian literature cannot be elaborated on any more than it already has, nor can its influence on Indian storytelling, which, even in a different yuga, seeks to evoke parallels and create counter interpretations from this great epic and its generational cast of characters for successive generations of audiences.

These reinterpretations have ranged from regional retellings to political narratives to sociological commentary, such as Irawati Karve’s “Yuganta.” The explosion of modern literature in India has meant novels from individuals as disparate as MT Vasudevan Nair and Chitra Banerjee, exploring the Mahabharata narrative from the perspective of one of its characters.

No matter which interpretation, retelling, commentary, or novel protagonist, the many scribes of the many versions of the Mahabharata corpus have all made space in one form or another for the character of Karna. The character of Karna and his treatment through the epic gives fodder for political theorists to launch critiques, for sociologists to examine the time’s prevailing norms, and for other characters to gain shades that go against their conventional positioning as hero and villain. In short, the complexity of the Mahabharata is best summed up in the stanzas about Karna’s life and sad fate.

Must Read: Why Women-Centric Films in Hindi Cinema are not Necessarily Feminist Films?

Karna’s enduring appeal—across storytellers, intellectuals, and ordinary people alike—doesn’t rest only on the familiar themes of violence’s futility, tragic birth, or the incisive insights scholars like Karve draw from his life; it also lies in how his story seems to foreshadow the spirit of the Kaliyuga itself. In essence, the Kaliyuga is an age of darkness, an age where the gods have turned their backs on man, and men resort to their lowest selves.

It is wholly appropriate that the Karna-esque protagonist in “Deewar” is actively confrontational with the god in the temple, while cherishing a talisman of other, non-traditional religious connotation, with little realization that the forces behind both entities are one and the same, the lost talisman ensuring his death at the threshold of the temple.

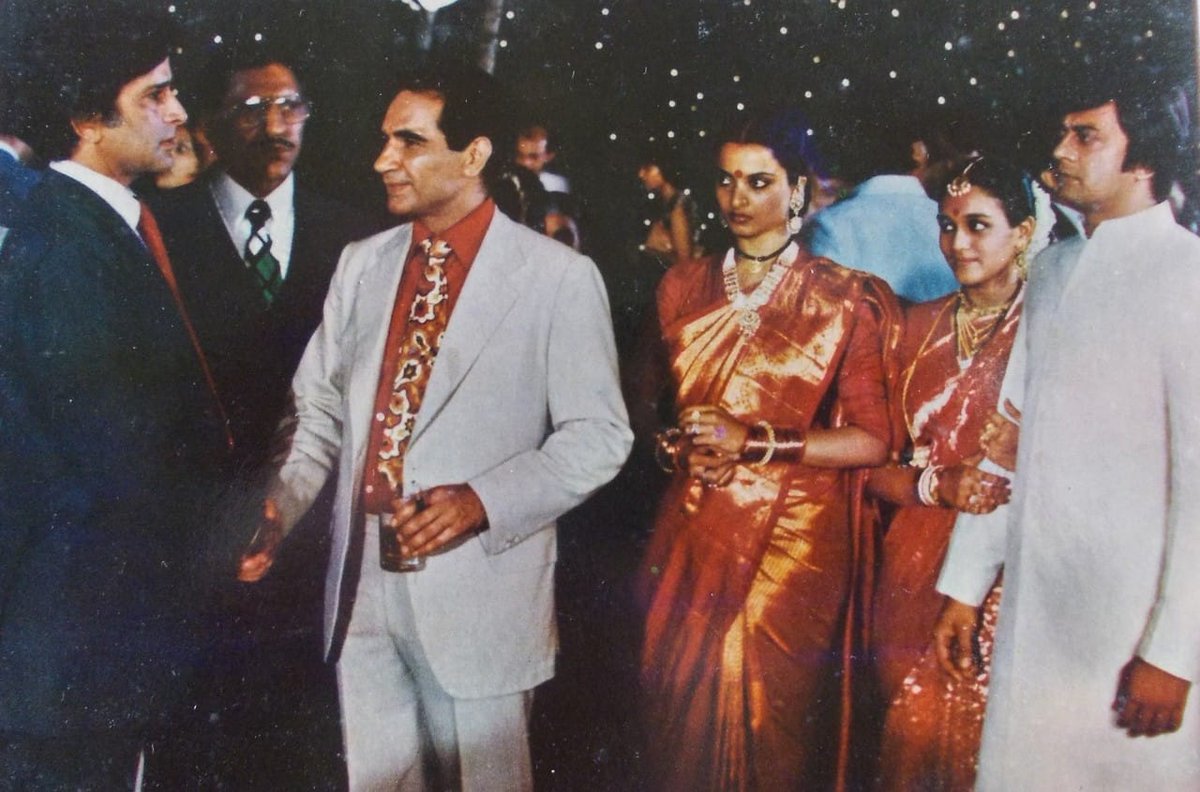

Despite, or rather because of the impact divine interventions have in his life, Karna is closest to the modern age man, and it is wholly appropriate that the Shyam Benegal-directed modern adaptation of the Mahabharata, “Kalyug,” is at its most emotionally resonant when it focuses on the Karna equivalent played by Shashi Kapoor. Kapoor’s inherent warmth and sophisticated spirit make him perfect in the most fleshed-out role of the film.

Watching Shashi in a role so close to the Vijay persona that Amitabh Bachchan played opposite him in “Deewar” makes one mourn the many years he was typecast as the “softer” leading man, while also feeling grateful for his later collaboration with Benegal, which left no doubt about his brilliance as an actor.

It isn’t just Kapoor who stands out. Several other performers leave a powerful impression through their closeness to Karan. AK Hangal, in particular, brings Bhishma’s deep weariness—the burden of the dynasty he carries and the exhaustion of a long life—to his final conversation with Karan. Even the young Sunil makes a mark, chastised by Karan for fighting his elders’ battles—a painfully ironic moment that makes the child’s death echo not only Abhimanyu but also Ghatotkacha, both of whom were unwittingly killed by the very man trying to protect them.

It isn’t just the minor parts like Sushma Seth’s Savitri but even the more central performers and parts who find their footing in their moments with Karan, be it Victor Banerjee who is terrific as the impulsive, insecure Dhanraj, an externalized contrast to Shashi’s restrained act, or Anant Nag’s intensity that is a refraction of Shashi’s pitch as Arjuna was to Karna. A history is communicated in the glances Dhanraj gives Karan or the stares Bharat (Nag) throws at him.

The breakdown of Bharat, Anant Nag’s character, is given an unsettling touch by the ambiguity of his head cradled in the lap of his sister-in-law, played by Rekha, whose Supriya is most interested in the hints to her relationships with Karan and Bharat, further underlining how similar these committed foes are. The unique status of Karna as a warrior forsaken by gods makes him perfect as the centre of Benegal and Karnad’s post-religion vision of the great epic, where gods are found as mere ornaments and government reigns supreme, be it as income tax or police.

Here, the battle of astras turns into a turf war over government-sanctioned machinery, but the rousing and cathartic moments of the epic are briefly alluded to in a Kathakali performance that is quickly avoided by the characters. The Bhima equivalent is only accidentally responsible for the violence he is usually associated with, and Krishna, despite being played by Amrish Puri, is a minor part. The film is awash in the grey shades of the epic, with neither side worthy of any sympathy. The Yudhistara equivalent is, in fact, mocked for avoiding the harsh truth by his family.

Also Read: Strong Women, Strong Stories: How Female Characters Can Captivate Audiences

The creative decision to strip away the divinity and focus on the family feuds, or squaring the Mahabharata in the Kalyuga (the age of godlessness), is undercut by the film’s extreme dependence on the material it seeks to subvert. The central conflicts in “Kalyug” seem overheated on their own, and entire character arcs are dependent on how well the viewer recalls the Mahabharata. There is no emotional resonance in the breakdown of this family, as one is never privy to the backstories of the characters except by way of referencing the Mahabharata, and one is left admiring the film from a distance rather than being awash in its turmoil, except for Karna.

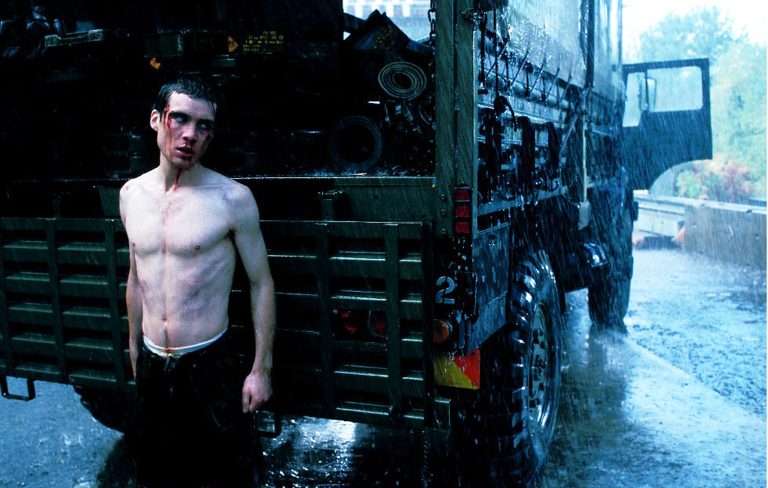

There is, of course, “Thalapathy,” which, despite similarities in intent and image making (a frame from “Kalyug” carries the seed for the famous lighting choices in “Thalapathy”), scales down on ambition and narrows focus on the quartet of Karna-Duryodhana-Arjuna-Draupadi, resulting in a more resonant narrative that is accessible to viewers on its own strengths.

The mythological origins of the Mahabharata are so deliberately stripped away in “Kalyug” that even Vanraj Bhatia’s score feels industrial, almost like the harsh clang of machinery. This stands in stark contrast to Ilaiyaraaja’s extraordinary music for “Thalapathy,” which draws on hymns, Carnatic traditions, and religious motifs. His score suits a modern world still haunted by myth—alive with temples, rituals, and echoes of the divine.

The Mahabharata endures, and its corpus is only set to grow with the advent of newer technologies, allowing greater freedom and mediums of expression for individuals who have spent their lives encountering its themes, subplots, and influences in numerous forms. The great epic, compiled at a time before Christ, has found newer interpretations even in the art form of the 20th century, and these interpretations, especially “Kalyug,” “Thalapathy,” and “Deewar,” remain some of the most iconic cinematic works from India.

![Melancholic [2019]: ‘Japan Cuts’ Review – Soaked in Ennui](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/40570045793_6cfe3222b9_o-696x391.jpg)

![Diverge [2018] : Standing Up To Your Past And Present](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Diverge-Movie-1.jpg)