There’s something about the inside of a taxi, especially at night, which invites meaningful conversations and sometimes even confessions. Perhaps it’s because the stranger behind the steering wheel will be gone from your life in fifteen minutes, or maybe it’s simply that cities after dusk belong to a different species of human being, those who work while others sleep, who traverse empty streets like astronauts navigating the loneliness of space. Jim Jarmusch understood this when he directed “Night on Earth,” his 1991 anthology film that remains one of cinema’s most profound explorations of intimacy.

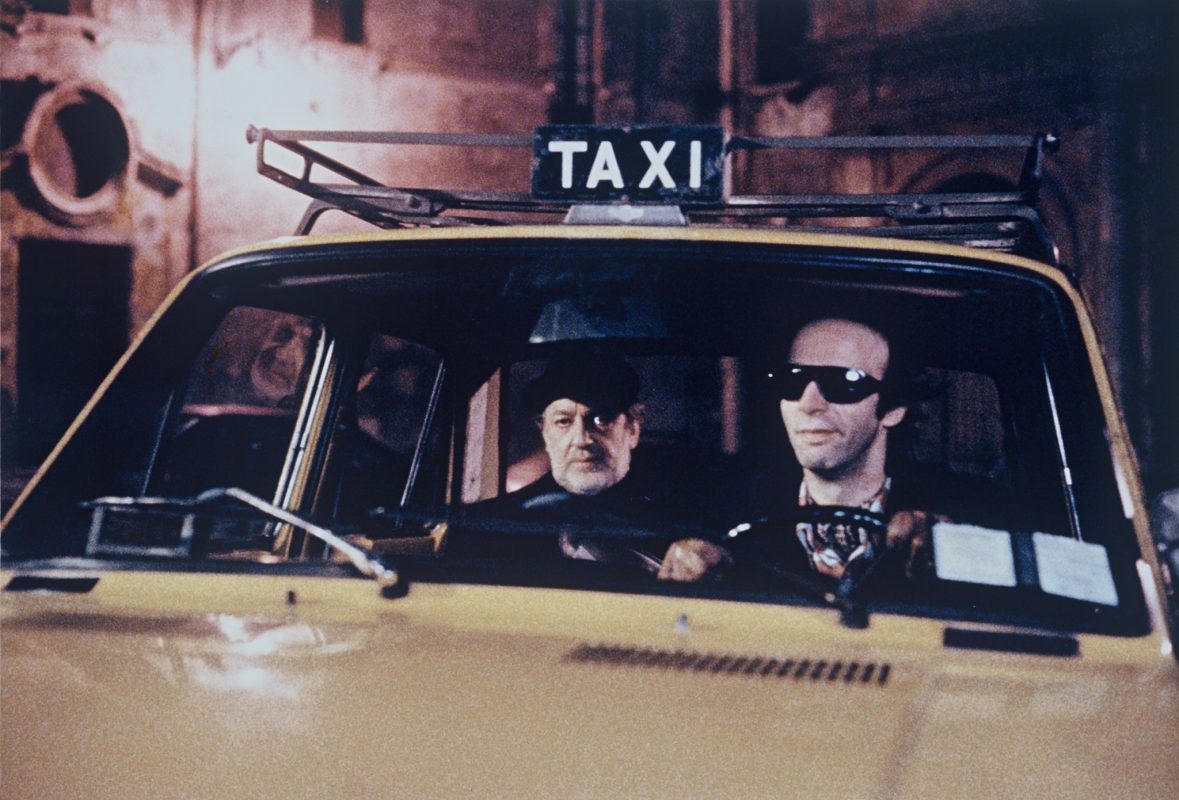

The premise is surprisingly simple: 5 taxi rides across 5 cities, which are Los Angeles, New York, Paris, Rome, and Helsinki, all occurring roughly simultaneously as night falls across different time zones. However, Jarmusch isn’t interested in plot mechanics or narrative connections between these stories. He’s after something more elusive: the strange chemistry that occurs when strangers share temporary space, when the social scripts we usually follow break down in the fluorescent glow of a taxi’s interior.

What’s remarkable about “Night on Earth” is how Jarmusch uses the anthology structure not to showcase variety for its own sake but to build a cumulative argument about human connection across cultures. Each episode operates as a variation on the same question: what happens when we’re forced into intimacy with someone we’ll never see again? The Los Angeles segment introduces us to this tension through Winona Ryder’s mechanic Corky, who deflects Gena Rowlands’s Hollywood agent with dreams of machines instead of stardom. It’s a conversation about ambition and authenticity, but in reality, it’s about how we perform different versions of ourselves depending on who’s watching.

The New York story takes this further. Helmut, the East German immigrant who can barely drive, navigates Brooklyn with the help of his increasingly frustrated passengers. What could have been merely farcical becomes something more tender. Here’s a man who has just arrived, and the orientation of his new home is still alien, and yet these strangers in his backseat change their behaviour from irritation to compassion, teaching him not just how to drive but how to exist in this new city. It’s Jarmusch arguing that cities don’t just contain people. They create ongoing collaborations between strangers who have no obligation to help each other, but they do it anyway.

While You’re Here, Also Check: 10 Best Roberto Benigni Performances, Ranked

By the time we reach Paris, it’s around 4 AM. Jarmusch has established his rhythm enough to undermine it. The blind woman and her Ivorian driver don’t follow the expected script where the sighted person learns wisdom from disability. Instead, their conversation is complicated and occasionally uncomfortable. She refuses his curiosity about color, about whether she dreams in images. He’s genuinely interested but doesn’t know how to express it without sounding condescending or prurient. This is perhaps the anthology’s bravest vignette because it refuses the easy emotional payoff. These two people cannot connect at all, and Jarmusch is honest enough to show us that not every meeting ends on an understanding note.

The Rome vignette, featuring Roberto Benigni’s frenzied confessions to a dying priest, initially seems like pure comic relief, and it is exhausting in ways both intentional and not, but keeping it between Paris’s failed connection and Helsinki’s crushing bleakness, it serves a purpose. Benigni’s character talks and talks and talks, filling every silence with stories of sexual escapades, and we realize he’s doing what all these characters do: trying to stave off the loneliness that defines urban existence. The priest’s heart attack becomes almost metaphorical; the weight of other people’s stories can literally kill you, but we keep sharing them anyway because the alternative is worse.

Then Helsinki arrives like a gut punch. After all the humor and occasional warmth of the previous stories, Jarmusch ends with three workers competing to tell the most tragic story from their lives. It’s almost unbearably dark, and many critics found it tonally jarring, but this is precisely Jarmusch’s point. The night doesn’t always offer connection or comfort. Sometimes it just offers witnesses to suffering, people who can sit with your pain for the length of a taxi ride and then drive away into the pre-dawn darkness.

Jarmusch’s recognition that contemporary urban life is fundamentally lonely, and that we rely on fleeting rituals—taxi rides, late-night diners, chance encounters—to briefly pierce that isolation without asking too much of one another, is what binds the five stories together. Rather than exaggerating the significance of these connections, Night on Earth’s genius lies in its respect for their transient nature. These interactions don’t change people’s lives. Nobody transforms or learns a profound lesson. People simply converse, exchange brief moments of comprehension or miscommunication, and then part ways.

Jarmusch wrote the screenplay in about eight days, and you can feel that spontaneity in the dialogue’s naturalistic rhythms. With the help of Tom Waits’s melancholic score, which sounds like loneliness given musical form, and Frederick Elmes’s cinematography, which captures the unique nocturnal texture of each city, Jarmusch creates a world in which the insomniacs and night workers form their own society with rules distinct from those of daytime civilization. The camera is primarily limited to side windows and windshields, a formal restriction that some people find restrictive but which actually heightens the cramped intimacy of these interactions.

The film’s structure does highlight some of its shortcomings. The anthology format tests patience at 129 minutes, and the tonal whiplash between segments can seem more like uneven execution than deliberate contrast. Viewers are especially divided during the Rome segment. Depending on your tolerance for Benigni’s unique energy, you may find his performance to be either brilliant or unbearable. Additionally, the five-cities-one-night idea seems almost too neat, as though Jarmusch felt compelled to respect the structure rather than allow the stories to develop naturally.

Also Check: All Jim Jarmusch Movies Ranked

However, these flaws seem to fit Jarmusch’s vision in some way. Real-life interactions between strangers aren’t always tonally consistent or perfectly balanced. Certain conversations make you feel invigorated, while others leave you exhausted. Even in its meticulously staged scenes, “Night on Earth” manages to achieve a certain documentary authenticity by refusing to smooth out these variances.

The film’s patience is what has aged most noticeably. “Night on Earth” understands that boredom and discomfort are essential to human interaction, having been made in a time before smartphones erased the awkward silences that punctuate these rides. Conversation matters, but so do the pauses. Confession carries weight, yet so do the moments when characters briefly retreat from intimacy, turning toward the passing streets beyond the window.

More than three decades later, “Night on Earth” has shaped numerous anthology films and television series, proving how stories connected by shared concerns rather than plot can accumulate unexpected power. More importantly, it remains a vital record of how we navigate the central paradox of urban life: existing among millions, yet fundamentally alone, brushing against strangers who may, for a fleeting moment, make that solitude bearable.

Jarmusch’s film offers no easy remedies or consolations. It simply observes that, on this particular night on Earth, we are all passengers moving through darkness in metal boxes, occasionally sharing space with other travelers whose inner lives remain opaque, yet whose basic hunger for connection mirrors our own. Sometimes, that is enough. Often, it is not. Still, we keep climbing into these taxis, hoping that the evening’s stranger might glimpse something in us that we could not name until we were sealed inside a moving car, committed to a conversation with no graceful exit.

![Hilda and the Mountain King [2021] Review – A beautifully animated film that is optimistic about a better world](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Hilda-and-the-Mountain-King-1-768x432.jpg)