Chandraprakash Dwivedi’s “Mohalla Assi” unfolds like an argument that refuses to settle, a conversation overheard in the labyrinthine gullies of Varanasi where language is never polite, faith is never abstract, and politics is never distant. What makes the film linger in the mind long after its cacophony subsides arises from its audacity in satirising Brahminical entitlement and from its irreverent dismantling of sanctimony, as well as from the way it situates women within this masculine theatre of outrage, commerce, and wounded pride, revealing in gestures that appear casual and in moments that seem incidental the gendered cost of ideological rigidity.

The film often receives attention for its explosive dialogues and its critique of the commodification of religion in liberalised India, yet an equally urgent current flows through its portrayal of how women inhabit this world, how they move through the debris of male anxieties, how they absorb, negotiate, recalibrate, and at times quietly redirect the energy of a neighbourhood that perceives itself as the custodian of eternal truth while it simultaneously adapts to the tourist economy, the English-speaking influx, and the shifting hierarchies of post 1990s India.

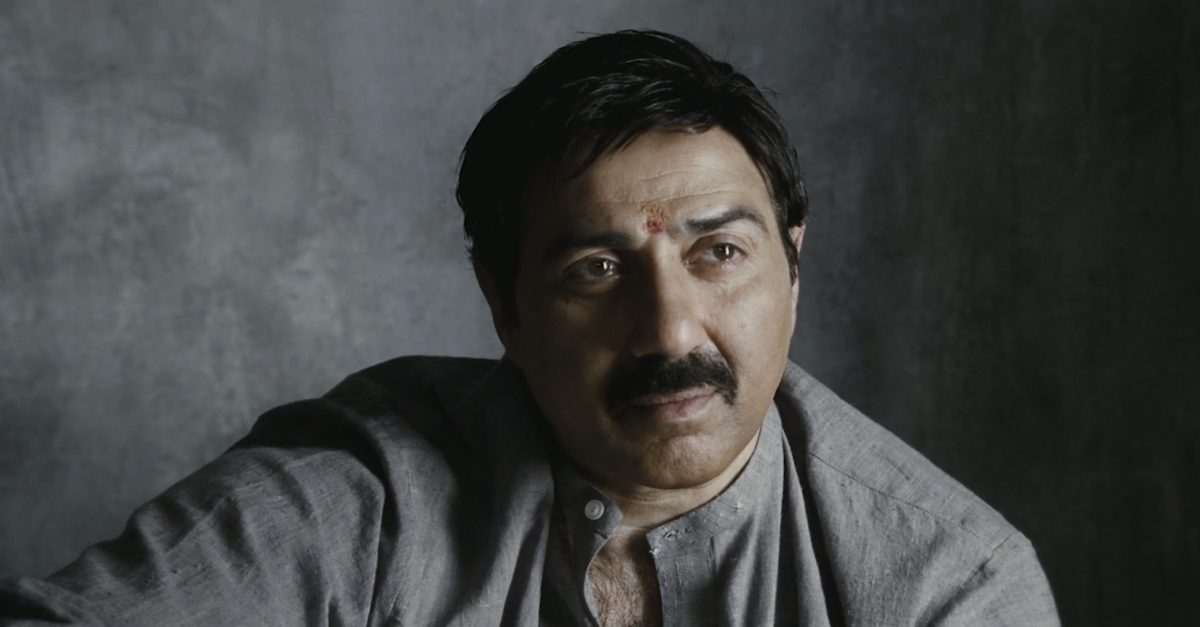

In that tension between permanence and transition, the figure of the Brahmin male appears erudite and proud and deeply invested in ritual authority, at once comic and tragic, a participant in modernity who speaks the language of tradition, holding tightly to scriptural capital even as the ground beneath him reshapes itself into a marketplace where Sanskrit shlokas travel as cultural currency for foreigners and the sacred river functions as both spiritual axis and global spectacle.

Within this form of a political space, the women reveal the subtler fractures of the Brahminical order, since, while the male characters debate authenticity and purity in public squares and tea stalls, the women’s lives illuminate how purity operates as a regulatory ideal, how the rhetoric of spiritual superiority draws strength from the shaping of female bodies, voices and desires into disciplined forms that sustain communal honour.

The satire, while directed at caste arrogance and the theatrics of religious commodification, expands into an exploration of the patriarchal scaffolding that gives Brahminism its everyday texture. This shows that this very Brahminical structure thrives on the idealisation of the chaste and self-sacrificing woman, the celebration of her endurance as virtue, and the framing of her silence as grace.

In tracing these patterns, the film offers a layered vision of a neighbourhood in transition where caste privilege adjusts itself to capitalism, the elements of sacred knowledge circulate as service, pride mingles with precarity, and the women stand at the intersection of continuity and change, sustaining households, interpreting shifts in economy and culture with pragmatic intelligence. They are found participating in arguments with wit and clarity, and embodying in their daily negotiations the intimate dimensions of a political satire that examines Brahminist

India not as abstraction but as lived social practice, textured by affection and irritation, by reverence and commerce, by ritual and improvisation. Through this densely woven portrayal, the film invites reflection on how power, gender, and faith coalesce within the ordinary rhythms of Assi, creating a social world whose humour carries insight and whose noise carries the quiet resonance of structural truths.

In observing the domestic spaces of “Mohalla Assi,” one senses that the public debates spilling across tea stalls and ghats find their echo within the interiors of modest homes, where brass utensils glint beside framed deities and the sound of ritual chanting drifts into kitchens thick with the scent of boiling lentils. Within these rooms, the women hold together the fragile architecture of everyday life, managing finances with attentive precision, stretching limited resources across school fees, groceries, and ceremonial obligations, mediating conflicts that arise from bruised pride and wounded ego, and confronting with steady clarity the practical implications of their husbands’ ideological fervour.

The film renders these negotiations with a textured intimacy, allowing women to articulate irritation, sarcasm, amusement, and occasionally open dissent in tones that arise organically from daily life, so that their words puncture the inflated rhetoric of Brahminical pride with a grounded realism that feels both humane and incisive. This ordinariness carries immense significance because it situates them as thinking participants within a social order shaped by inherited hierarchies, a structure they navigate with intelligence and adaptability, subtly reshaping its contours through conversation, budgeting, persuasion, and care, rather than through overt proclamations.

The satire functions here through contrast, as the grand narratives of cultural preservation and scriptural authority unfold in public arenas. The women measure the tangible consequences of those narratives within domestic space, weighing the cost of ritual orthodoxy against the needs of a changing economy.

They give rise to the residue of the idea of democracy thriving merely at “Delhi” and “Pappu’s stall”. In a neighbourhood where the erosion of traditional patronage encourages Brahmin men to transform ritual knowledge into marketable service for tourists and language students, it is often the women who translate that transformation into sustainable routine, calculating earnings, absorbing fluctuations, and stabilising the household with emotional labour that carries dignity and resilience.

Their presence illuminates how a system that celebrates them as embodiments of tradition draws vitality from their labour and composure, how reverence becomes intertwined with responsibility, and the language of honour acquires substance through their everyday efforts, so that the transition from priestly authority to service provider unfolds as a shared recalibration of identity in which women emerge as pragmatic interpreters of change, sustaining continuity while participating actively in the redefinition of what it means to inhabit Brahminical space in contemporary India.

A particularly revealing instance of this shared recalibration of identity unfolds in the scene where Marlene arrives at Pandey’s home, bringing with her the quiet weight of foreign presence into a space saturated with ritual familiarity. And almost immediately, the rhythms of the household begin to reorganise themselves around her needs, with Pandey turning to Savitri repeatedly, asking her to prepare tea again and again, to boil water, to arrange small comforts and accommodations that allow Marlene to carry on with her daily routine in an unfamiliar land.

Also Read: The 10 Best Hindi Films Of 2018

The scene unfolds with an air of casual normalcy. Yet beneath its surface, one senses the intricate choreography of labour that sustains this new economy of hospitality, for Savitri’s movements between kitchen and courtyard, stove and serving tray, enact the very transformation that the film explores, the shift from priestly authority grounded in scriptural inheritance to service grounded in global exchange. While Pandey articulates the ideological defence of tradition in public, it is Savitri’s quiet efficiency that enables the household to participate in the commodified spirituality that now circulates through Assi.

Her repeated acts of making tea, heating water, and adjusting to Marlene’s expectations reveal how the rhetoric of cultural pride acquires practical form through domestic effort, and the performance of authenticity depends upon the seamless integration of foreign demand into Brahminical space. The presence of the Western seeker reshapes gendered labour within the home, inviting Savitri into a role that extends beyond ritual wife into cultural mediator and facilitator of exchange.

In this dynamic, reverence and responsibility converge, because Savitri embodies the gracious host that tradition extols. She also shoulders the invisible work that makes this hospitality viable, and the scene gently illuminates how Brahminism adapts to modernity not only through public debate and political satire but through the steady, embodied work of women who translate ideology into lived practice, turning cultural capital into everyday service while sustaining the dignity of the household. In doing so, she participates actively in the redefinition of what it means to inhabit Brahminical identity within a rapidly globalising India.

The film’s political satire on Brahminist India operates through exaggeration and profanity, yet beneath its coarse humour unfolds a layered and attentive interrogation of how caste privilege reshapes itself within the currents of liberalisation, how inherited authority adapts to the grammar of capitalism, and how the assertion of cultural supremacy travels alongside an acute awareness of shifting relevance, so that the defence of tradition emerges as a performance addressed simultaneously to the neighbourhood, to the nation, and to an imagined moral audience that watches and evaluates. In this theatre of resistance, the Brahmin male figure, primarily Pandey Ji, speaks with conviction about civilisation, scripture, language, and sacred geography, presenting himself as guardian of an ancient order whose continuity ensures the moral spine of the country, and his speeches carry passion and theatrical flourish.

Yet the satire gently reveals how this guardianship finds new life within market structures that transform ritual knowledge into purchasable experience, how the ghat becomes both pilgrimage site and cultural showcase, how Sanskrit classes accommodate foreign seekers, and how the discourse of preservation circulates through economic exchange that binds spirituality to service.

The intensity with which cultural authenticity is articulated coexists with an acute awareness of transformation, and the film captures this coexistence through scenes that blend humour with insight, allowing ideological fervour to share space with practical improvisation, and within this dynamic, the gender dimension acquires central significance. This happens since the same discourse that positions Brahmins as custodians of civilisation positions women as custodians of honour, aligning their comportment, speech, clothing, and mobility with the moral legitimacy of the community, so that the body of the woman becomes an emblem of cultural continuity.

In “Mohalla Assi,” this linkage appears vividly within domestic interactions and public commentary, as women move through spaces saturated with ritual symbolism while carrying out the tangible work that sustains households, and their presence reveals how honour gains material expression through their labour, composure and adaptability, how the language of tradition acquires texture through their daily routines, and how cultural pride draws vitality from their participation.

At the same time, the film portrays women navigating these expectations with awareness and intelligence, engaging conversations, responding with wit, negotiating responsibilities, and thereby shaping the lived reality of Brahminical space, so that the satire extends beyond a critique of male posturing and opens into a broader reflection on how caste, gender and economy intersect within contemporary India, forming a complex social tapestry where reverence intertwines with responsibility, performance blends with pragmatism, and identity evolves through the continuous dialogue between inherited structures and present circumstances.

At the same time, the film presents women as deeply enmeshed in the social structures around them, navigating a world shaped by ritual, hierarchy, and expectation, with their gestures, expressions, and decisions carrying the weight of tradition alongside the necessities of daily life. They inhabit spaces where power circulates unevenly, absorbing symbolic reverence while translating it into practical forms of authority within households, neighbourhoods, and marketplaces. Their engagement with the world is neither passive nor performative but grounded in intelligence, attentiveness, and continuity, blending insight with action, observation with intervention, and care with calculation.

Their presence demonstrates that Brahminist patriarchy operates through collective social affirmation as much as through male assertion, distributing responsibility, influence, and expectation across genders in ways that sustain continuity while allowing adaptation to emerging pressures, and in observing the subtleties of daily routines, one sees the quiet calibrations, negotiations, and interventions that preserve the rhythm of life and ensure the endurance of custom.

The satire of the film achieves its depth by capturing these layered interactions, juxtaposing grandiose claims of authority with the intricate, often understated work of women, whose routines, conversations, and interventions give shape to the social and economic life of the mohalla, embodying the compromises, adjustments, and foresight that uphold both households and neighbourhoods.

The language of the film, profane, earthy, and unapologetically local, situates women within an environment where respectability, decorum, and social performance are constantly measured, evaluated, and negotiated, allowing their voices to carry clarity, authority, and subtle critique. Even in moments of quiet observation, the film conveys the interplay between tradition, power, and adaptation, showing that the preservation of culture thrives less on heroic gestures than on the persistent, intelligent, and discerning contributions of those whose labour and presence anchor daily life, translating inherited authority into lived practice and sustaining the continuity of Brahminical space in ways that are at once practical, insightful, and profoundly humane.

If one steps back, “Mohalla Assi” appears to stage a larger meditation on what happens when a community built on inherited authority confronts the erosion of that authority in a democratic, market-driven, and politically polarised nation, and the satire of Brahminist India becomes a way of interrogating how identity hardens in moments of uncertainty, how nostalgia becomes a political resource, and how the language of victimhood can be appropriated by those historically positioned at the top of the hierarchy.

Within this meditation, the women function as barometers of change, their lives registering the shifts more concretely than the men’s speeches do, and while the film does not centre them in a conventional narrative sense, their presence reframes the satire, reminding us that any critique of caste power that ignores gender would remain incomplete.

What feels compelling about “Mohalla Assi” is not that it offers a definitive statement on Brahminism or patriarchy, but that it opens a space where these structures can be examined without reverence, where laughter becomes a mode of critique, and where the contradictions of a society in transition are allowed to surface in all their discomfort.

In considering the aspect of women within this political satire, one might sense that the film gestures towards a broader question about who bears the weight of cultural preservation and who benefits from its prestige. While it does not resolve this question, it invites reflection on how caste and gender intertwine in the making of modern India, how the defence of sacred tradition can coexist with economic opportunism, and how, in the crowded lanes of Assi, the voices that speak the loudest are not always the ones who sustain the neighbourhood’s fragile continuity.