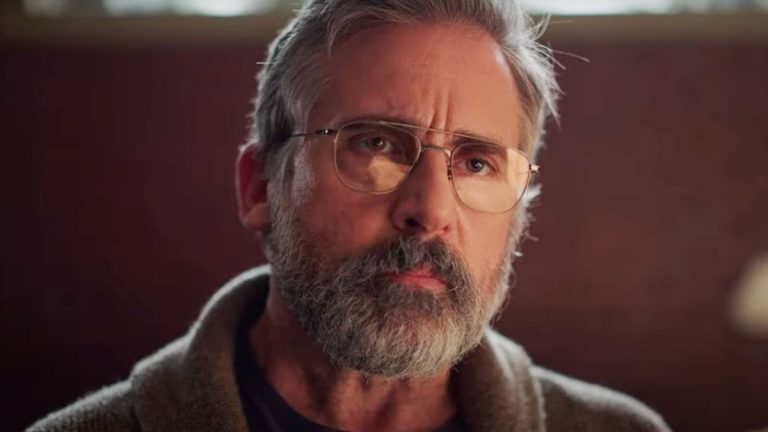

Pavan Malhotra has carved a niche for himself as a copper-bottomed supporting actor in the business. With Tabbar, Malhotra finally gets one of the meatier roles his talent can handle, and he chews on that meaty role to perfection. As Sardar Omkar Singh, an experienced retired police officer who is wary of the system, he spent the better part of his life navigating, he becomes the only sane person in his family to steer out of a crisis.

The crisis in question could be the premise of any prestige television show; a case of mistaken luggage causes Maheep Sodhi to come to Singh’s house, to retrieve the luggage mistakenly exchanged by Harpreet AKA Happy, Singh’s elder son. The luggage in question was exchanged in a train during their return from Delhi to Jalandhar. Unbeknownst to Omkar, Happy and most importantly Maheep, one of the primary constituents of that bag, a packet is misplaced by Tegi, Omkar’s younger son, who mistook the rectangular packet as an iPhone case. Enraged by the deception, as Maheep comes to the conclusion, he returns to the house of Omkar Singh’s, quite literally guns blazing, threatening to blow Tegi’s head off by pointing the barrel of his gun straight at Tegi’s mouth.

It’s a harrowing experience, made furthermore harrowing by the acute helplessness of Pavan Malhotra as Omkar Singh and Supriya Pathak as his helpless wife, scared to death for her children. The experience comes to a resounding conclusion when Happy, who had managed to escape to the other room, manages to shoot Maheep, straight to the head. The resulting image of blood and brain matter on the family photograph attached to the mantle is one which is going to be etched into your head forever.

The above inciting incident takes place within a tensely deliberately paced first episode itself. What follows is Omkar Singh bending very possible rule he can think of – both legal and societal, to plug this rapidly sinking ship, and save his family, especially his elder son from going to jail. This bending of the rules so far near the point of breaking, all in the name of family, is where the show’s underlying thesis statement lies. The question arises – “How far would you go to protect your family?” Tabbar answers with a terse “As far as you can imagine”.

What makes Tabbar stand out is the scope as well as the tones, and the balance it takes to juggle all these tones and give each of the tones and its characters their due. Maheep’s Brother Ajeet Sodhi, a quietly terrifying Ranvir Shorey, is one of the two building contractors having political ambitions. These machinations, while not in the foreground or taking its time away from the main story, plays slowly and effectively in the background, until it comes to play in the final two episodes, to satisfying and frankly surprising climax.

The sense of location and place too is what gives Tabbar a unique voice, and doesn’t make it devolve into an Udta Punjab 2.0. Jalandhar in Tabbar is a city stuck between two tones – the violence and the drug-heavy mob life which promises a far better life of excess, and the traditional middle class rooted family values, with people who would resort to blackmail as well as counter-blackmailing to maintain that sense of family.

[tabs]

[tab title=”Checkout” icon=”iconic-info”]The 25 Finest Hindi Films of the Decade (2010s)[/tab]

[/tabs]

It’s fascinating to see chaos, gunfight, strong violence and even pulpy situations that audiences are bound to imagine what would happen to these hapless individuals. Tegi, tied by the leg and hanging upside down, his head perilously close to a furnace, is one of these chaotic situations. But the filmmaking is solid here, and nowhere does the chaos feel too designed, or completely derailing itself from the story. There are elements which feel like they are part of a different universe altogether.

The presence of two assassins, a brother sister duo, feel like a part of a Coen Brothers film haphazardly included here for black humor, which felt unnecessary. The melodrama, the serious tone and the almost oppressive bleakness at times, feel very much at home here. And the imagery, the overhead shots, the blood seeping out from locked doors, rats chewing away at brain matter; these images manage to reinforce the tone of the oppressive bleakness. And nowhere does this bleakness feel more pronounced than in Supriya Pathak’s depiction of the matriarch of the Singh family.

An accessory to murder now, Sargun’s mental degradation due to overpowering guilt and increasing mental trauma manifests itself in increasingly bizarre visuals – from the presence of crows on the staircase, to blood on her hands she is unable to wash off, to blood and writings on her walls she is unable to erase, and the reanimated bodies of the dead manifesting as agents of her guilt. The final episode, running 46 minute long, is mainly dedicated to her increasing and inevitable mental devolution, with Omkar Singh trying to steer this rapidly sinking ship.

The show is not perfect. Tegi’s overall character arc is very superficial in comparison to every other character in the show. Happy’ s character stuck in a love triangle, very much reminiscent of 90s Bollywood, feels superficial until the writers subvert the usual trope into something far more real. And that’s how Tabbar manages to save itself from falling into conventions, by restraining itself to the realistic world it has successfully managed to create. But why Tabbar manages to make an impression for me, and immediately cement itself top something resembling great, are the final moments. If the studio plans for a second season I would be happy for the creators and the actors. But as how the story ends, there is no other way I would like the story to end – bleak, mesmerizing, sad and terrifying.

![Alles ist gut Netflix [2019] Review – Bold and Scarred](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Alles-ist-gut-768x441.jpg)

![Battle: Freestyle [2022] Review – Confused and Problematic Film that Disappoints](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Battle-Freestyle-2-768x432.jpg)