Andrei Tarkovsky is one of the greatest filmmakers who died young in exile. He is often called the inventor of “a new cinematic language,” which is intimate, poetic, and often lyrical. Having worked on only seven films in his career, all his films are classic and highly influential. Won’t be a hyperbole to call his work a bible of cinematic language that explores the profound depth of the human consciousness in the quest for the spiritual arc. Every film is intimate and personal and carries a legacy of its own.

The conversation presented here took place in March 1985 in Stockholm. At that time, Tarkovsky worked on his — as it turned out — last film, a deep metaphysical treatise whose title, The Sacrifice, was as significant as that of his previous film.

Q: In Mirror you have presented us your biography. What kind of mirror did you use? Is this a mirror-like Stendhal’s, a mirror which travels down the road, or is it a mirror in which you have found yourself, learnt something about yourself that you didn’t know previously? In other words: is this a realistic work or a subjective auto-creation? Or perhaps your film is an attempt to put together pieces of a broken mirror and frame them within the cinematic image, to compose a complete whole from them?

Andrei Tarkovsky: Cinema in general always creates a possibility of putting pieces together into a whole. A film consists of all of the separate shots like a mosaic — of separate fragments of different colour and texture. And it may be that each fragment on its own is — it would seem — of no significance. But within that whole it becomes an absolutely necessary element, it exists only within that whole. That’s why cinema is important to me in the sense that there is not, there cannot be any fragment in the film which wouldn’t be thought through with an eye for the final result. And each individual fragment is coloured so to speak with a common meaning by the entire whole. That is, the fragment does not function as an autonomous symbol but it exists only as a portion of some unique and original world. That’s why Mirror is in a sense closest to my theoretical concept of cinema.

You are asking: what kind of mirror is it? Well, first of all — this film was based on my own screenplay containing no invented episodes. All the episodes were really part of our family history. All of them, without exception. The only made up episode is the illness of the narrator, the author (whom we do not see on the screen). By the way, this very interesting episode was necessary in order to convey the author’s spiritual crisis, the state of his soul. Perhaps he is mortally ill and perhaps this is the reason for the recollections that make up the film — as with a man who remembers the most important moments of his life before he dies. So this is not simple violence done by the author to his memory — I remember only what I want — no, these are recollections of a dying man, weighing in his conscience the episodes he recalls. Thus the only invented episode turns out to be a necessary prerequisite for other, completely true recollections.

Related Read: Every Andrei Tarkovsky Film Ranked

You are asking whether this kind of creation, this creating of one’s own world — is this the truth? Well, it is the truth of course but as refracted through my memory. Consider for example my childhood home which we filmed, which you see in the film — this is a set. That is, the house was reconstructed in precisely the same spot where it had stood before, many years ago. What was left there was a… not even the foundation, only a hole that had once contained it. And precisely at this spot the house was rebuilt, reconstructed from photographs. This was extremely important to me — not because I wanted to be a naturalist of some kind but because my whole personal attitude toward the film’s content depended upon it; it would have been a personal drama for me if the house had looked different. Of course, the trees have grown a lot at this place, everything overgrew, we had to cut down a lot. But when I brought my Mum there, who appears in several sequences, she was so moved by this sight that I understood immediately it created the right impression.

One would think: why was such an elaborate reconstruction of the past necessary? Or not even the past but what I remembered and how I remembered it. I didn’t try to search for a particular form for the internal and subjective memories, so to speak; on the contrary — I strived to reproduce everything the way it was i.e., to literally repeat what was fixed in my memory. And the result turned very strange… It was for me a singular experience. I made a film with not a single episode composed or invented in order to interest the viewer, to attract his attention, to explain anything to him — these were truly recollections concerning our family, my biography, my life. And despite the fact — or perhaps because of it — that this was really a very private story, I received a lot of letters afterwards in which the viewers were asking me the rhetorical question: “How did you find out about my life?” And this is very important, very important in a certain inward sense. What does it mean? I mention it as a very important fact in a moral, spiritual sense because if someone expresses his true feelings in a work of art, they cannot remain secrets to others. If the director or the author is lying, makes things up artificially, his work becomes entirely…

Maria Tarkovskaya, Andrei Tarkovsky’s mother, 1932.

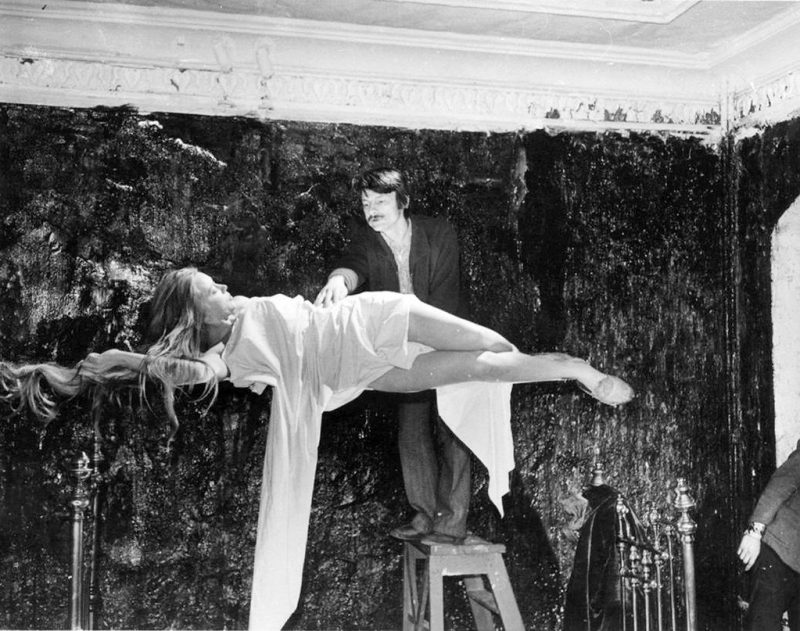

Margarita Terekhova in Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Mirror (1975)

“Sophisticated”…

Andrei Tarkovsky: Yes. In Italy they say cervellotico, troppo cervellotico, it means “artificial, contrived.” Such work does not move anyone. So a mutual understanding between the author and the audience, without which work of art does not exist, is possible only when the creator is being honest. Which doesn’t imply an honest author automatically means an outstanding work, ability and talent remain the basic prerequisites, without artist’s honesty, however, true artistic creation is impossible. I believe if one tells the truth, some kind of inner truth, one will always be understood. Do you see what I’m saying? — even when the problems shown are most complex, the sequence of images, formal structure of the work most complicated — for the creator the fundamental problem will always be honest.

Concerning its structure, Mirror for me is, in general, the most complicated of my films — as a structure, not as a fragment considered separately but precisely as a construction; its dramaturgy is extraordinarily complex, convoluted.

Just like the structure of dreams or reminiscences. After all, this is not just a regular retrospection.

Andrei Tarkovsky: Right. This is not a regular retrospection. There are many such complications there which I don’t even completely understand myself. For example, it was very important for me to have my mother in some scenes. There is one episode in the film in which the boy, Ignat, is sitting… not Ignat… what was his name? — the author’s son, he is sitting in his father’s empty room, in the present, in our times. This is the narrator’s son although the boy plays both the author’s son and the author himself when he was a boy. And as he is sitting there we hear the doorbell, he opens the door and a woman enters and she says: “Oh, I think I’ve got the wrong place” — she was at the wrong door. This is my mother. And she is the grandmother of this boy who opens the door for her. But why doesn’t she recognise him, why doesn’t the grandson recognise her? — one has completely no idea. That is — firstly, this wasn’t explained by the plot, in the screenplay, and secondly — even for me this was unclear.

Not everything in life is understandable and clear…

Andrei Tarkovsky: No, for me it is — how can I put it — coming to terms with various emotional bonds. It was extremely important for me to see the face of my mother, this is a story about her after all, who enters the doorway uneasily, kind of timidly, a bit à la Dostoyevsky, à la the Marmyeladovs. She says then to her grandson: “I think I’ve got the wrong place.” Can you imagine this psychological state? It was important for me to see my mother in this condition, to see her face when she is confused when she feels timid, ashamed. But I understood it too late to compose some precise subplot, to write the screenplay in such a way as to make it clear why she didn’t recognise him — whether it was because her eyesight was bad… It would have been a very easy thing to explain this. But I simply said to myself: I’m not going to invent anything. Let her open the door, enter, not recognise her son [sic] and the boy won’t recognise her, and in this state, she will leave and close the door. It’s a state of the human soul which is particularly close to me, a state of some kind of despondency, spiritual restriction — it was important for me to see this. It’s a portrait of a human being in a state of certain humiliation, a certain feeling of being brought down. And when one puts this side by side with the scenes of her youth — this episode reminds me then of another one: when as a young woman she comes to that doctor to sell her the earrings. She is standing in the rain, she is explaining something, talking about something, why in the rain? What for?

Perhaps it would be much better if there were no riddles of this sort. But there are several episodes like that completely with no explanation, incomprehensible, we just have no idea what they mean. For example, people would say: “and who is this older woman sitting over there asking him to read the letter from Pushkin to Chaadayev? What woman is this? Akhmatova?” — Everybody says that. She, in fact, does look a bit like her, she has the same profile and she could remind her. The woman is played by Tamara Ogorodnikova, our production manager, she was in fact already our production manager for Rublov, she is our great friend whom I photographed in almost all my films. She was like a talisman to me. I didn’t think this was Akhmatova. For me she was a person from “there” who represents a continuation of certain cultural traditions, she is attempting at all cost to tie this boy to them, tie them to a person who is young and lives in this day and age. This is very important, in brief — it’s a certain tendency, certain cultural roots. Here is this house, here is the man who lives in it, the author, and here is his son who somehow is influenced by this atmosphere, those roots. After all, it is not precisely delineated who this woman is. Why Akhmatova? — A bit pretentious. This isn’t any Akhmatova. Simply put, it is precisely this woman who mends the torn thread of time — just as in Shakespeare, in Hamlet. She restores it in a cultural, spiritual sense. It’s a bond between modern times and the times past, the time of Pushkin or perhaps a later time — it doesn’t matter.

A very important, most important experience I gained with this film was that it turned out to be as important to the audience as it was to me. And it didn’t matter that it was a story only about our family and nothing else. Thanks to this experience I saw and I understood many things. This film proved there was a bond between me as a director, as an artist if you will, and the people for whom I worked. That’s why this film turned out to be so important to me because when I understood that, nobody could complain to me that I did not make films for people. Although everybody complained about it later anyway. But I couldn’t make this complaint to myself anymore.

Q. When we talked about your heroes we called them wanderers, pilgrims. And here is a question: for your hero, wanderer, pilgrim, is there any chance to break through the threatening him chaos of events? Time is merciless in your works, it turns everything into ruin: time and events harm and annihilate the characters, everything material. Do you believe in the permanence of values such as faithfulness, a sense of one’s dignity, the right to individual self-realisation?

Andrei Tarkovsky – Hmm. It’s difficult to call this a question, it’s more like a multitude of various problems you’ve listed. It’s very difficult for me to answer such a broadly formulated question. On the one hand, you mention the merciless time which annihilates the characters — and then you say: “and everything material.” That’s not very clear to me. After all those characters are not exclusively “material.” Everything material undergoes destruction but these characters are not only matter — first and foremost they are spirit.

Of course.

Andrei Tarkovsky – That’s why I always thought it important — to the extent human spirit is indestructible — to show matter, which is subject to decay, destruction — as opposed to spirit which is indestructible. You won’t find it in Rublov yet; although we obviously are dealing with destruction, annihilation there but this is in a sense moral destruction, not the opposition of the spiritual against the physical. While in Stalker or even, say, already in Mirror — we have for example this house which doesn’t exist anymore and perhaps a touch of the spirit of the place which remains forever.

The mother, when she goes outside — remember that? — always remains the same. It was important for me to show that this figure or soul of the mother was immortal. And the rest undergoes decay; this is, of course, sad — as a soul feels sad sometimes watching itself leaving the body.

There is some nostalgic longing in it, an astral sadness. It is also self-evident to me that this destruction does not concern the characters, only objects. That’s why it was important to obtain this contrast — so as to present reality from the perspective of transitoriness, if not for its having grown old, outliving its time, and its existence at a particular time in general — while man always remains the same, or more appropriately, does not remain the same but develops, to infinity.

You talk about dignity. Obviously, dignity is very important, most important. And you talk about the path, the journey. If we are to talk about a journey, also metaphorically, then one has to say that it is, in fact, unimportant where one arrived, what’s important is to embark upon a journey.

In Stalker, for example…

Andrei Tarkovsky – Always, under all circumstances. And in Stalker? Perhaps, I don’t know. But I wanted to say something else — that what is important is not what one accomplished after all but that one entered the path to accomplish it in the first place. Why doesn’t it matter where he arrived? Because the path is infinite. And the journey has no end. Because of that, it is of absolutely no consequence whether you are standing near the beginning or near the end already — before you, there is a journey that will never end. And if you didn’t enter the path — the most important thing is to enter it. Here lies the problem. That’s why for me what’s important is not so much the path but the moment at which a man enters it enters any path.

In Stalker, for example, the Stalker himself is perhaps not so important to me, much more important is the Writer who went to the Zone as a cynic, just a pragmatist, and returned as a man who speaks of human dignity, who realised he was not a good man. For the first time, he even faces this question, is man good or bad? And if he has already thought of it — he thus enters the path… And when the Stalker says that all his efforts were wasted, that nobody understood anything, that nobody needed him — he is mistaken because the Writer understood everything. And because of that, the Stalker himself is not even so important.

Something else is interesting in this context. I wanted to make another film, a sequel to Stalker in which… — This was possible only in Russia, in the Soviet Union, it’s impossible now because the Stalker and his wife would have to be played by the same actors. Something else is important here: that he changes, he doesn’t believe anymore that people could go to this happiness, towards the happiness of self-transformation, an inner change. And he begins to change them by force, he begins to force and kidnap them to the Zone by means of some swindles — in order to make their lives better. He turns into a fascist.

And here we have how an ideal can — for purely ideological reasons — turn into its negation; when the goal already justifies the means man changes. He leads three men to the Zone by force — this is what I wanted to show in the second film — and he does not shy away even from bloodshed in order to accomplish his goal. This is already the idea of the Grand Inquisitor, those who take on themselves sin in the name of, so to speak…

Salvation.

Salvation. This is what Dostoyevsky had been writing about all the time.

In Demons…

In Demons and in The Brothers Karamazov. In Demons he even didn’t write about that — there he, in general, negates the first impulse, whatever it could be, even the noblest one… He negates even that.

That’s Demons.

Yes, that’s Demons. But in The Brothers Karamazov, he wrote about socialism, exactly about all those people who take on themselves the sin of violence in the name of happiness of the masses.

Reference:

“Z Andriejem Tarkowskim rozmawiają Jerzy Illg, Leonard Neuger”, in Res Publica (1), Warsaw 1987, pp. 137–160.

Read More on Andrei Tarkovsky;

-

ANDREI TARKOVSKY AS AN EXISTENTIALIST CINEMATIC PHILOSOPHER

-

NOSTALGHIA REVIEW [1983]: A SPIRITUAL SPACE LOOSELY SUSPENDED IN TIME

![Poser [2021]: ‘Tribeca’ Review – A volatile dissection of the need to belong](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Poser-2-Tribeca-highonfilms-768x432.png)