Every Pride Month, most movie fans revisit the same handful of films. Brokeback Mountain, Call Me By Your Name, and Portrait of a Lady on Fire are often lauded as groundbreaking depictions of LGBTQ romance. But one movie is too often criminally neglected in these conversations on film, radical acceptance, and romance. Before any of these movies could break ground in the mainstream, 1985’s Desert Hearts opened up audiences’ minds with one of the most infectious love stories of the past fifty years that not only gives birth to one of the most incredible on-screen couples but gives spectators hope that even the most seemingly conservative communities can make room for love.

Based on the 1964 novel by Jane Rule, the film takes place in Reno, Nevada, in 1959 and focuses on the budding love story between Vivian, a Columbia English professor staying in Reno to get a divorce, and Cay, a young artist whose sexual openness both attracts and scares Vivian. Though decades apart, director Donna Deitch’s world was not so far off from Jane Rule’s. Rule set the novel during the Eisenhower administration, a time when McCarthyism reigned, and a wave of fear of a gay takeover was in the air.

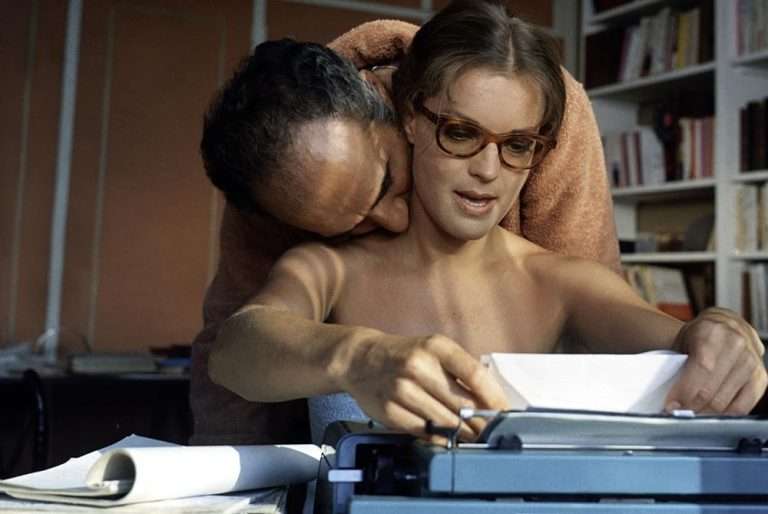

In the 1980s, Deitch was contending with a Reagan administration that was content to ignore the AIDS crisis as long as it stayed within the LGBTQ community. Though Deitch was able to fundraise for the film thanks to influential names like Gloria Steinem and Lily Tomlin, its two lead actresses, Helen Shaver and Patricia Charbonneau, were both warned by their agents that if they did this film, they’d never work again. Even with this outside pressure, Deitch, Shaver, and Charbonneau took over the open spaces of the West, long believed to be the property of men, years before mainstream movies like Thelma & Louise.

This complexity is built into the story. How could it be that in Reno, then the divorce capital of the world, a beautiful and meaningful romance could be born? Desert Hearts does away with any preconceived notions of who belongs in the vast open spaces of the American West. In this stereotypically masculine world, Cay and Vivian can carve out a safe space of their own. For them, the open road symbolizes a kind of sexual freedom. When the repressed Vivian first arrives at the train station, she remarks that she doesn’t know what to do with this open space.

She really means she wouldn’t know how to express herself with this potential freedom from divorce. Her romance with Cay thus becomes intertwined with her initiation into the Country & Western culture. The first time the two spend an extended period together, Cay takes Vivian horseback riding. The next time they get together, Cay helps Vivian pick out a fringe western shirt, then she takes her gambling and then to a honky tonk bar. The relationship becomes physical only after Cay and Vivian leave the bar and go for a drive.

The Country & Western scene is an integral part of their relationship, and, much to the surprise of most audiences watching Desert Hearts, independent women are an integral part of Country & Western music. Having spent much of the film’s budget on the soundtrack, Deitch cultivates a collage of songs that echo the times, the emotions, and the quietly radical breakthroughs. Scattered throughout the film are some of the greatest hits by Patsy Cline, a woman who changed not only Country music but the American music industry landscape with her independent personality. The film even ends with “I Wished On the Moon,” an innocent love song that was actually written by a victim of the blacklist and one of the most biting satirists, Dorothy Parker. Parker and Cline may have created songs that seem to fit into the conservative moral code, but they often used these traditional styles as a cover for more subversive ideas.

Even Cay’s best friend and greatest ally, Silver, sings country music at her engagement party. Any audience member with preconceived notions and fears about this culture’s conservative and intolerant nature is immediately put at ease. The reality is much brighter than what they may have feared. Cay is able to forge a life for herself that isn’t built on self-hatred and secrecy. Her close friends know and accept her for who she is. The only person in her life that doesn’t is Francis, the mistress of her late father, Glenn, and her surrogate mother. The conservative parental figure disapproving of their child’s lifestyle is a tired stereotype for gay stories, but Deitch uses it to create a more exciting juxtaposition.

A feeling of meaninglessness has plagued Francis since the death of Cay’s father. It’s a sadness that unknowingly unites her with Cay’s struggle. When explaining her relationship with Francis to Vivian, Cay stumbles, saying she isn’t her mother and that she isn’t anything to her. In Reno, a city where legal, familial status is essential, she can’t fathom that she was Cay’s mother even though she didn’t give birth to Cay or legally marry Glenn. Maybe the law won’t recognize that fact, but it’s true. It’s also true of Cay’s relationships. Her love for Vivian won’t receive state recognition in their lifetime. Francis’ fears for Cay are not that she will enter into a life of sin but that she will end up like her. When the two finally reconcile, they share a long hug on the street, and when they pull away, Francis jokingly remarks that they’d better stop before people start talking about her too. Francis’ closure comes when she realizes she and Cay are a part of the same struggle, and that is OK.

The final victory of the film comes from Vivian, who has spent much of her life deep in the closet. She hides from the openness of the West by barricading herself in her room, not even talking to the other women who are also temporarily residing in Reno to obtain a divorce. When she first begins a sexual relationship with Cay, nothing much changes. She still barricades herself in her room, only this time with a companion. But unlike other gay period dramas, this does not feature a perfunctory tragic ending. With Cay’s help, Vivian learns to marry her own sensibilities to those of the West. As Vivian boards her train home, she doesn’t put on a cold front or adversely tearfully beg Cay to come with her. Instead, she asks Cay to come on the train to talk.

When Cay asks what Vivian wants from her, she simply says, “Another 40 minutes with you.” Deitch’s romance is not one of possession. Cay and Vivian don’t belong to each other, and we don’t know if they will end up together. However, 40 minutes at a time, they’ll unabashedly and unashamedly enjoy the open road together.

![Still Walking [2008]: Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Elegiac Masterpiece](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/aruitemo-768x396.jpg)

![The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part [2019] – Still Awesome](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/The-Lego-2-High-on-Films-2019-768x322.jpg)