Sometimes two people can be very similar and yet very different. Sometimes their problems rhyme and circumstances chime to make up a harmonic hymn, or rather a tragedy. Aditya Kripalani’s “Devi aur Hero” (2019) is one such tale. A tale of two people trapped in the weird world of sex. A take on two very different people, from very different classes, regions, and communities, inherently caged by male perversion. Moreover, it’s a story of how their characters, circumstances, and connections shape them. The ultimate clay that forms an idol of a Devi and an idol Hero.

Madonna & Mistress

Dressed in a schoolgirl fetish outfit, her neon-blue hair tied into twin ponytails, Kaali stands on the balcony, seemingly contemplating suicide, when a group of thugs bursts in and kills the guard assigned to watch over her in her captor’s absence. All this with the Mumbai local train whistling in the background, packed with people shown in the opening credits of the movie. (quite an introduction, I must admit.) She runs in a taxi whose driver was a fan of flop films, an interesting yet odd ode by the director, right in the middle of a serious scene.

Suffering from occasional blackouts, Kaali meets the “hero” Vikrant in his clinic, where we find out that she was enslaved and raped by a rich brat for a year after being imprisoned in sex work all her life. Aditya here uses dramatic irony, as the audience, unlike Kaali, already knows that Vikrant is a sex addict and is almost scared of female interaction.

In a span of days, Kaali went from a position of inferiority to a position of privileged client, from being scared of a man to sharing her life story with a man, from whore to worshipped, from Mistress to Madonna. The Madonna-mistress complex is one of the few palatable models given by Freud (who called it psychic impotence), which states, men with this complex either see women as saintly Madonnas or debased whores.

Later interpreted in feminist movements, both roles end up reducing female autonomy by either holding their bodies restrained or their thoughts trapped. Men in the movie see Kaali as an object of sexual pleasure, the definitive “Mistress”. Even the “hero” is not able to control his lust. Fuelled by the horrible advice from his senior doctor, Vikrant attempts to be the saviour she needs, making a Madonna-esque monolith from a girl he is meant to treat. Much like a religious extremist trying to “protect” his deity, ultimately hurting the deity and the humans.

Like Travis from “Taxi Driver,” Vikrant rolls in the same dirt he despises so much. He is frustrated with the men who have hurt Kaali, but his sex addiction makes him the same as the others. When faced with rejection or dejection, instead of working on themselves, they try to find value in “saving” women. Betsy, like Kaali, would have liked a simple friend in her life, but men in their lives either end up hosting them with the horrors of a whore or resort to deifying them with the dignities of a Devi.

Manjulika & Mental Health

Soon, Kaali is diagnosed with Dissociative Identity Disorder and develops two personalities inside of her: a middle-aged Sikh woman, Mamta, and an old lady, Rukmani. Both sprouting from the two major sexual abuse instances in her life. Despite his flaws, Vikrant suggests an ingenious way to handle the situation and establish communication between the personalities.

Throughout the movie, the disorder is used as a plot device to further the narrative. Instead of turning Kaali into a supernatural medieval queen thirsty for vengeance, the disorder is used as conflicting voices in her head. Like the devil and the angel trope, Mamta keeps telling her to control herself and stray away from the world, while Rukmani tells her to give herself a little time and space to breathe, mirroring the roles of mother and grandmother in a toddler’s life, referencing the id, ego, and superego from Freud’s notebooks.

Looking from an angle of sympathy, Vikrant is also a patient of a mental disorder – Compulsive sexual behavior disorder – which manifests as a pattern of behaviour involving intense preoccupation with sexual fantasies and behaviours that cause significant levels of mental distress, cannot be voluntarily curtailed, and risk or cause harm to oneself or others.

Unlike Kaali, Vikrant doesn’t have a Mittal in his life to trap him; he is Mittal for himself, and he can’t run from the Mittal housed in his own body. He is not only disgusted with the deeds he revels in, but he is also scared he might harm someone someday, probably someone close to him. He does hurt Kaali. Not just by trying to rape her, but also by not giving full disclosure and recommending her to a better psychiatrist.

Full disclosure – I barely have any idea of real-life therapies and patients, but the portrayal of therapy sessions between the two characters felt intriguing at best and disappointing at worst. Sessions that are barely five minutes in length and Vikrant diagnosing Kaali with a serious disorder in just the second after the meet, ring a warning sign in your brain. They make you think, “Surely real-life sessions are not like this,” during the watch, which is definitely not a good sign for a movie. All this would have gone unnoticed had the scenes of Kaali paying Vikrant been omitted. Going to live in a slum colony after paying a thousand for a five-minute session with a psychiatrist who ultimately wants to get in your pants?

Doesn’t sound like a great advertisement for therapy, does it? Add to it the consistent non-diegetic sound whenever Kaali and Vikrant converse, which starts to come into direct notice after a few scenes. Not to mention the unnecessary “Apna Time Aayega” joke by Vikrant to a new client. If the purpose was to show the gloomy side of therapy as a business, Aditya surely succeeded, but if the idea was to set psychotherapy as a necessity, things could have been a lot better. In a country where we still have a long way to go in mental health, it is fair to demand better from directors, at least the ones who are in it for the love of art and personal voice. Or maybe I am just nitpicking, and we need to stop finding accidental heroes in filmmakers.

Maradona

On 22nd June 1986, in the quarter finals against England, Diego Maradona flung his left arm above his head and punched the ball into England’s goal post, giving Argentina a goal lead. They went on to win the match by 2-1 and then the tournament. When asked whether he scored it illegally, Maradona said “it was made a little with the head of Maradona, and a little with the hand of God”. Despite his angelic answer, the world knows Maradona has committed a sin, the original sin of football – touching the ball with your hands, and still Maradona became a hero, illegal or otherwise, accidental or not, a hero nevertheless.

Vikrant had committed a far more heinous but another original sin for a psychiatrist, letting his emotions take over his judgment for the client. Not only couldn’t he fulfil his duties as a psychiatrist, but he also didn’t even become a good friend. From masturbating to her photo to calling her in his hellhole house and then ultimately trying to rape her. After being betrayed by a young boy who called her “didi”, there are no words that can do justice to how Vikrant’s story panned out, and despite his condition, Vikrant just couldn’t be a “hero” for me. I kept thinking the movie name is ironic, and neither of them is supposed to fulfill the title given to them.

In an interview, when asked about Vikrant not having to face any consequences of his actions, Aditya, inter alia, said, “…There was also some luck,” which, however irksome, is not false in itself. Vikrant, like Maradona, became an accidental hero overnight. Despite what they did and how they did it, they just got saved by the sheer fact that they didn’t get caught committing the crimes, and we can’t change that. But we can choose our heroes carefully.

Maradona had a lot going for him as a footballer, but Vikrant? As I said, his illness just doesn’t make him sympathetic enough to be let go of his sins. However puny, maybe living with his sins is his only punishment. Living in the perpetual dirt of knowing what he tried to do.

Much later in life, Maradona confessed in his autobiography, “Now I can say what I couldn’t at that moment, what I defined at that time as The Hand of God. What hand of God? It was the hand of Diego!” Maybe Vikrant can also confess someday, not for him, but for Kaali, who finally saw, in a flawed man, a Hero.

Mastectomy

During his attempt to rape Kaali, Vikrant finds out she has had a mastectomy, possibly for breast cancer treatment. This shocks him to the core as he steps back and realises what he was about to commit. Using the scar (literally and metaphorically) of a past traumatic event to prevent the crime was an interesting choice, and one can only imagine what went through in Vikrant’s mind at that time. Maybe looking at the scar made him realise that Kaali is a human being with a past and a future, which dropped the objectification glasses from his eyes.

Or maybe the scar shattered his fantasy image of a sexualized, “perfect” female body, which a sex offender might imagine, which in turn killed his overtly sexual emotions at the time, giving back the control to his logical brain. Or maybe it was a sad attempt to free the male lead of his illnesses magically at the cost of past trauma borne by the female lead.

Maybe the whole sequence can be viewed as a little summary of the plot of the movie and the life of Kaali. Had Vikrant received some help earlier in his life, he wouldn’t have ended up like this. Had Kaali received a little pause from the consistent barrage of sexual abuse she received all her life, she could have been in a much safer and comfortable spot. Of course, had other men seen Kaali for who she is and what scars she wears, they too would have stopped from disrobing the final flimsy layer of protection she held so tightly to herself… maybe.

Mario & Mary

Mario runs and jumps and dashes and gallops through the plains and above the pits to save the all needy, oh so feeble Princess Peach. Turns taller, fights goombas, and even starts shooting fireballs from his arms. The Super Mario – the ultimate saviour story. The peak of masculine narrative. And the apogee of the male gaze. Perseus battles the dragons to save Andromeda. Peter Parker picks a fight with Green Goblin to rescue Mary Jane. Damsel in Distress as a trope is as old as the phrase “as old as time”.

To Aditya’s credit, “Devi aur Hero” is not a typical damsel-in-distress film. In the trope, Damsels are generally of high class or at least in the middle section of society, which quite clearly Kaali can’t qualify for. And damsels are definitely not known for their martial arts prowess. In that sense, Kaali is more “Kill Bill” than “Kabir Singh.” But maybe that’s where the differences end.

Starting from the very premise that Kaali desperately needed a male friend in her life to get ahead of her past. Not once but twice, we were shown that she tries to find a male friend in Keshav and Vikrant. Maybe the idea was to show the differences between her inner voices and outer experiences, the former being feminine and the latter being masculine, but that might be a stretch with no actual insight.

Later, we see Vikrant supporting Kaali and assisting her in taking revenge on the sex offenders—as a friend, with no repercussions for his own actions toward her. Yet, I like to think that Kaali never truly needed Vikrant; she saved herself. As Minogue declares in her magnum opus, “I don’t need a shining star, and I don’t want to be rescued.”

Assassinating the predators is not uncommon for Aditya’s movies, asking the uncomfortable yet unavoidable question of “violence by the oppressed” to our society. However, this ‘execution’ was not executed properly. Compared to “Totta Patakha Item Maal” (2018), which simmered the plot of vengeance on a low flame, “Devi aur Hero” threw a deep fryer at the problem, giving “the resolution” a runtime of mere 3 minutes.

Adding to it, we barely saw those villains earlier in the movie (except Keshav), greatly reducing the impact of their assassinations. While the villain who received the most runtime and got saved by sheer luck gets to “assist” the titular deity in her victory march, solve his own mental health problems by divine intervention of a female client, all this while being called a “hero”?

Male Gaze

Right from the start, why do we need to call the movie “Devi aur Hero,” and why do we need to name the female lead Kaali (and Rukmini, Mamta, Tirtha)? Is it only for the poetic metaphor? I do understand the mythological connection of Kaali killing Mahishasur, which is most popular in Bengal. But I think at this point we are well aware of the unnecessary burden such metaphors put on individuals.

Needless to mention the blatant hypocrisy of the way women who are called Devis are actually treated. Compare that to Satyajit Ray’s “Devi,” which, despite having its fair share of male saviour complex, actually showed what happens to a little girl when she is put on the pedestal of purity.

The same goes for Vikrant; had he not been called the “hero” right from the start, he could have been interpreted as a grey character or even an anti-villain. But the title burdened his character and the audience to be treated only as a “Hero”. Next, the long lingering shots of the shoulders and collarbones of Kaali during her therapy sessions.

Even if the motive was to show Kaali from the POV of Vikrant, it was still very uncomfortable to watch. It shouldn’t come as a surprise, but I really didn’t enjoy viewing a girl from the gaze of a potential sex offender. Compare that to the shots of Kaali swimming, which look like she’s finally liberated, she is finally finding a friend, and Rukmini and Mamta are finally quiet and letting her breathe.

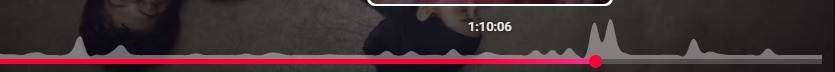

But maybe the most monumental yet miserable moment of the male gaze was not in the movie, but in the medium itself, in the act of watching the movie. This movie is available only on YouTube as of now, and YouTube has a feature called “Most Replayed”.

You see the three spikes? They are the most replayed scenes, and those are also the scenes where the men of the movie forced themselves onto Kaali, first Mittal, then Vikrant, and Keshav at last. The biggest spike is shot of Kaali’s breasts. Sometimes, watching the act of watching the movie tells us more than watching the movie. A lot can be written about this, but I’ll leave for everyone to make of it what they will. See the medium, look for the message, and find the meaning.

Meaning

The final shot lingers on Kaali walking out of her house at night, clutching a picture of herself with Saraswati—the brawn and the brain, the warrior and the wisdom. It hints at Kaali’s enduring commitment to finding Saraswati in Vikrant’s name, a dedication he ultimately acknowledges. She looked at Vikrant in a way no one else ever did—not even Vikrant himself. While he could only perceive her body and, in turn, reflect on his own, she saw much deeper. In conversations with Mamta or Rukmini, she glimpsed herself from multiple angles, constantly recalibrating her understanding of identity and agency.

Both characters existed in a perpetual tussle between mind and body, yet only Kaali transcended it—pulling Vikrant along like a hero completing a side quest. Descartes’ dualism may have failed to distinguish between the two, but temperament did. He could never look within; he lacked the inner sight she possessed. In Kaali, and in Vikrant as she perceived him, she saw the duality of “Devi and Hero.”

![God of Dreams [2022] Review: An Hodge-podge of several Dystopian fictional tales](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/God-of-Dreams-2022-768x432.jpg)

![The Crossing [2019]: ‘NYAFF’ Review – The Queen of Hong Kong](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/The-Crossing-highonfilms-768x512.jpg)

![Harakiri [1962] Review: Death Over Dishonour](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/harakiri-screenshot-1-768x432.jpeg)

![Heavenly Creatures Review [1994]: Friendship. Love. Imagination. Obsession. Murder.](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Heavenly-Creatures-768x478.jpg)

![‘Kidnapping Stella’ Netflix Review [2019]- Unimaginative but Thrilling Kidnapping Drama](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Kidnapping-Stella-768x325.jpg)