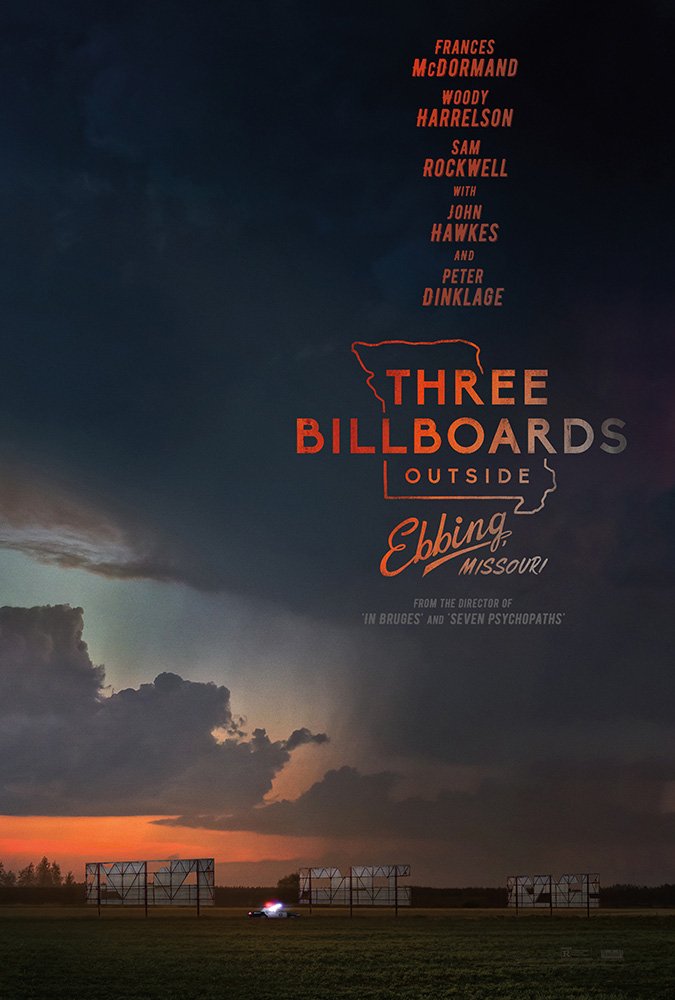

Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri [2017]: An Effective & Darkly Comic Outburst of Righteous Anger

Irish playwright and film-maker Martin McDonagh has got a gift for writing screenplays interlaced with dark humor. His hilariously deployed profanities and digressive yet sharp monologues gain more energy, when wickedly delivered by the right set of actors. As the one who penned seven critically acclaimed plays, McDonagh largely tells his story through dialogues, characters, and plot; the directorial aspects may not be particularly arousing, but certainly remains pertinent. In a way, we could say that McDonagh’s weaponizes the words he bestows upon his characters (who are often frustrated, sad, furious or numbed) to make their verbal confrontations more memorable than the violent ones. Right from his first shot at cinema, titled Six Shooter (2004) – a 27-minute film that went to win an Academy Award – McDonagh has depicted his penchant for blending criminality and human absurdity. The set-ups are pretty much farcical, but gradually gets to the deep emotional truth of the characters. With his third feature film Third Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017), the director includes all of his trademark elements and has concocted a fine complex script, whose underlying narrative strands aren’t overtly visible.

Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri has one of the instantly gripping story-lines; a carefully calibrated mixture of mystery, grief, and righteous anger. And, its foul-mouthed, quirky comedy oft pushes the scope of the premise’s tragedy and actively reconstructs the characters. Furthermore, Frances McDormand playing a steel-eyed woman is something wondrous to behold. Altogether, the Three Billboards is the more mature and surprisingly moving work from McDonagh that dispels viewers doubts after his slight sophomore slump (‘Seven Psychopaths’). The film opens on a peaceful stretch of road in a foggy morning, which sort of hints at the possible obscurities in the forthcoming narrative, and shows us the titular inert objects. When worn-down Mildred Hayes (McDormand) of Ebbing, Missouri passes through the three perfectly-spaced yet broken-down billboards, she gets an idea. She walks into the local advertising office, puts down $5,000 for the month’s rent, and provides the words to be put up on the billboards.

Mildred was the mother of a teenage girl named Angela Hayes, brutally raped and murdered on the same lonely stretch of road where the tattered billboards stands, seven months before the movie’s events begins. The crime remains unsolved, no suspects brought in for inquiry, and about to be forgotten by the town’s mostly indifferent populace. So the three billboards, where she calls out Chief Willoughby (Woody Harrelson), is the last desperate effort to get the local police force’s attention. Judging from Mildred’s seething anger, it’s also a declaration of war. What we soon realize is that Willoughby is actually a dedicated policeman, who does his best to manage his incompetent, racist, and homophobic sub-ordinates. Of course, he immediately wants the billboards to go down, but he’s also perplexed by their inability to nab the perpetrator. As he confronts and explains to Mildred that the perp’s DNA doesn’t match with their database and that there are literally no clues or eye-witness to the crime. But Mildred, understandably, rejects his excuses.

Willoughby also has his own personal tragedy to worry about. He has a beautiful, caring wife (Abbie Cornish) and two angelic daughters, but he’s been diagnosed with terminal cancer. The whole town, including Mildred knows about it. However, she doesn’t care and adds, “They (billboards) won’t be as effective after you croak.” The strong opposition against Mildred’s tactic, nevertheless, comes from Jason Dixon (Sam Rockwell), an oddball and allegedly racist police officer, who looks up to Willoughby, and believes in solving all problems with a beating. Dixon lives with his old, cranky mother, who gets ‘nostalgic’ about the days when the blacks were enslaved. In one of Mildred’s verbal stand-off against Dixon, she asks “So, how’s it all going in the n****er torturing business?”, for which he seriously replies, “It’s ‘Persons of color’-torturing business, these days”; a mild criticism on using politically-correct language to undermine the questionable showcase of prejudice. But, the film isn’t always keen on barbed social commentary and so much as uses these scenarios to conjure inky black humor. There are quite a few other cringe-worthy developments, which if not for the performances and savvy dramatization would look wholly problematic.

Three Billboards has a very tricky narrative tone, compared to McDonagh’s other two scripts. It’s really hard to create gallows humor (and make viewers laugh) when only few frames before the writer divulges the central piece of information about a teenage girl having been raped, immolated, and killed. However, McDonagh mostly succeeds at that without belittling the tragedy of the incident. The success, primarily, lies with casting of Frances McDormand, whose nothing-to-lose attitude and profound despair instills a grim power to the proceedings. Patronizing the Catholic priest with tempestuous monologue or soulfully ruminating to a CGI-rendered deer or knocking out the bullying teenagers, McDormand’s performance is equally heart-breaking and outrageous. Most of her actions incite our emotions to rally alongside her in the personal battle, and her blistering dialogue deliveries are so good. Somehow it seems the film’s naturalistic feel and mordant humor would have gone up in the flames, if not for McDormand’s towering presence. The writer also concentrates on Mildred’s borderline insanity, provoked by all those repressed anger and desire for retribution. The most interesting & unanticipated development here is the characterization of Willoughby. Brilliantly underplayed by Harrelson, he reflects Mildred’s imperfections and uncontrolled mania that ticks like a time-bomb.

The film would seem less appealing for those expecting a well-rounded crime/drama because McDonagh repeatedly plays up with our allegiance for characters and blows empathy into a character, written-off as an oaf and villain. Despite rooting for Mildred, we slowly start to feel that the exhibition of recklessness has eroded her perspective and reality. But, Sam Rockwell’s Dixon who is relegated to a punch-line in the initial scenes happens to confront his own crisis of responsibility and faith. On first look, it seems good; finding hope and redemption in an otherwise pigeonholed character. Dixon’s change of mind imparts complex emotional layers to the narrative. By making us to constantly shift the loyalties, McDonagh tends to say how people behave within the boundaries of their strictly limited perspective and choices stacked before them. With more of compassion and less of judgement, the constrained circumstances actively broaden. However, on hindsight, Dixon’s shift from being despicable bigoted cop to tragic figure feels a bit queasy, considering Mr.McDonagh’s early satirical notions. For a crime narrative, Dixon’s change-of-heart may adds profundity to the tale. But this clearly betrays the inherent social commentary, since Dixon’s redemption is as problematic as Officer Ryan’s transformation (in Crash played by Matt Dillon; although Dixon isn’t as sentimentalized as Matt Dillon’s character). It indirectly turns the film–maker’s presentation of racist overtures in small-town Americana into a mere fodder for designing the later good-guy character arc. I would have much preferred if the bits incongruously dealing with themes of political correctness, the media, identity politics are cut-off, and the narrative deals more with the uneasy dynamics between Mildred and others. By the way, was there any necessity for that ‘foreshadowing’ scene, where Angela Hayes’ last words, after an altercation with her mother Mildred, happens to be, “I hope i get raped on the way” (a jarring note in a narrative that tries to avoid melodrama).

In spite of such narrative and thematic strains, Three Billboards held my attention and left me with complex set of emotions, which are hard to decipher after a single watch. While usually in crime narratives, the display of righteous anger solves protagonist’s conflicts, here it asks what if that isn’t enough. What if nothing is wrapped up neatly and all that’s left to gaze is that ‘figurative’ bottomless void? Irrespective of the bit unconvincing 180-turn of Dixon, Mildred’s brief, beatific smile in the end as she travels in a sunny road may be hints at the possibility of some hope. Similar to Kenneth Lonergan’s Manchester by the Sea, McDonagh denies closure to the viewers, since the characters’ aren’t going to have that. They carry the option for transgressive violence and predilection for healing, like every other agonized, angered people.

Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri (115 minutes) boasts a wonderful dramatic scenario that zig-zags around audiences’ expectations and raises its stakes in unpredictable manners. Barring few irreconcilable & questionable narrative choices, the film remains as a compelling tragicomedy.

![Sanju Review [2018]: Stellar Performances Elevate Light Biopic](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/SANJU_HOF_1-768x327.png)

![The Phantom Carriage [1921] Review – A Startlingly Inventive Morality Play of the Silent Film Era](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/The-Phantom-Carriage-1921-768x559.jpg)