Do Not Expect Too Much From The End Of The World (2023) “CIFF” Movie Review: Romanian auteur Radu Jude makes films that are bombastic whirlpools, freely and wildly splintering any fixed directionality by chopping together varying styles and modes. He’s a restlessly inventive storyteller who pulls no punches in his staunch, often relentless critiques blasting off the state of affairs in Romania. Any viewer new to his work and stepping into this film will be presumably rattled by Jude’s habit of unleashing the full range and fury of his all-encompassing, spectacularly no-holds-barred ambition. His films do not necessarily lend themselves to easy viewings not because of anything extreme or gratuitous but for their sheer excesses in terms of ideas and counter-arguments railing at each other with noisy recklessness.

Jude obviously is not interested in making any of it palatable. He is the definitive postmodernist storyteller in myriad ways, gathering and then puncturing grand narratives. In this new film, he casts a wide net, and it is a testament to his genius that he keeps all of it in a firm grip. The scope of his anger surges out in all routes, crisscrossing the individual and society as they range from questions of categorizing private-public property to larger, brave inquiries into holding a citizenry accountable for the systemic rot, the way in which Jude converges his intellectually bustling telling with technical and stylistic fractures is a thing of marvel.

Shrewdly edited by Jude’s longtime collaborator, Catalin Cristutiu, the film hops with occasional deliriousness between two parallel tracks. Extended snippets and whole sequences from another Romanian classic, Lucian Bratu’s 1981 film, Angela Moves On, are sandwiched within the outer narrative. While initially, the similarities between the tracks seemed to be the names the protagonists share and jobs that include long driving hours, the echoes slowly start reverberating across the decades further into the film. Jude’s protagonist, Angela (Ilinca Manolache), is a production assistant driving around Bucharest to various prospective differently-abled people’s homes, tasked with taping their auditions for a corporate ad her company, Forbidden Planet, has been commissioned to make.

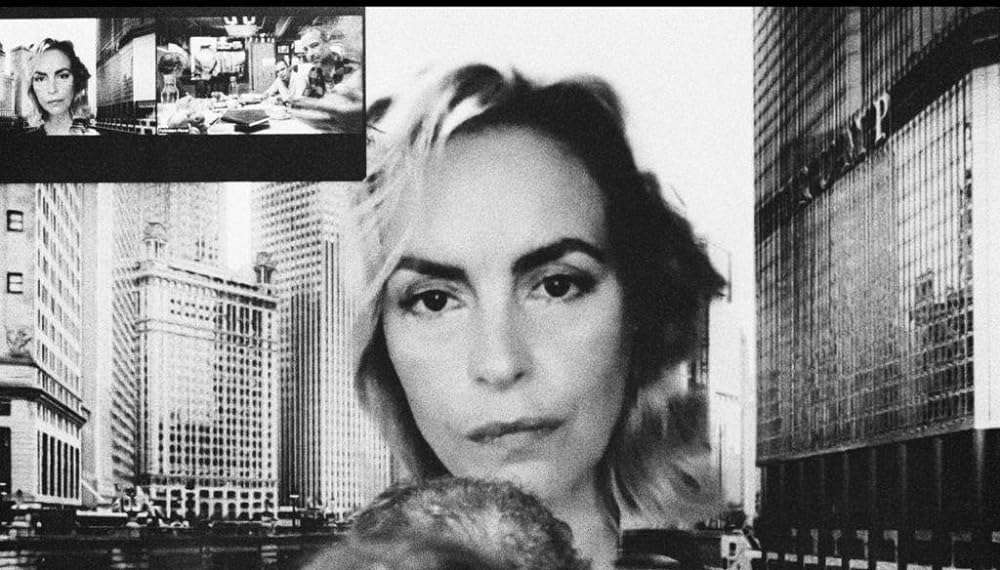

Most of Angela’s scenes are in monochrome, except when she puts on her alter ego. While the commissioning Austrian company claims the educational ad ostensibly aims to promote safe working conditions, the characteristic doublespeak of seemingly benign capitalism is excoriatingly exposed in the film’s monumental, ruthlessly incisive final half hour. In her visit to the candidate who eventually gets selected, Ovidiu, Angela strikes a rapport with his mother. Cristutiu smartly stitches the mother’s (played by Dorina Lazar herself) stories about her life and love, along with the flow of the trajectory taken by Bratu’s Angela.

Jude’s Angela also dabbles as a TikTokker, with filters of herself as a hideous, unibrow misogynistic man, Bobita, letting off steam in profusely cursing rants. Channeling a rowdy street hoodlum, Bobita’s colorful tirades are loaded with a volley of expletives and lewd jokes, not even sparing the British monarchy. Working extreme stretches, Angela airs her frustration and angst through this other motor-mouthed avatar. While this double-facedness can obviously be extended to the deceit of corporations, Angela even cheekily refers to the classic Jekyll & Hyde. Jude keeps interrupting any smooth narrative through these bursts of Bobita and fragments of Bratu’s film.

Bratu’s Angela (Dorina Lazar) is a taxi driver, and this track takes us back to the years Ceausescu presided over or, rather, as Jude’s Angela puts it, effectively destroyed Romania. Jude tends to obtrusively slow down the Bratu film, freezing frames occasionally, insisting on us to look deeply and sharply. As the two heroines are mostly at the wheel for chunks of the film, the space of the car is realized as one wherein relationships are forged, including a failed marriage for Bratu’s Angela, while a woman driving registers as an anomaly irrespective of the decade. The traffic has worsened, but men’s rude, limiting gaze persists.

Men in traffic hurl abuse the way of both the heroines. While Bratu’s Angela does not quite engage, Jude’s Angela hits back. Exhausted, overworked, and frequently coarse-tongued, this Angela navigates the world with an unapologetic sense of self-assuredness. Manolache has such a spitfire, charismatic presence, which she brilliantly uses to convey Angela’s desperate need for release and relief. When she asks her company bosses if she needs to head home and rest; otherwise, she will doze off at the wheel and die in an accident, her superior advises her to take a brief nap in the car instead. For all her slogging way overtime, getting her pay on time remains a struggle.

Radu Jude takes this theme of capitalist work culture and workers across rungs being driven to extremes by corporations and companies and zooms out to unforgivingly dig into the morass of contemporary Romanian society. There are, of course, the expectant sexism and corruption on blunt display but also trenchant critiques on the entrenched class-inflected prejudices of the country’s citizens, who are all too eager and quick to pile all the blame for present-day misgovernance and slights in public duty onto the damage of the communist years. Jude does not let anyone off the hook.

When Angela asks her company’s visiting Austrian client, Doris (Nina Hoss), about any truth to news regarding Doris’s company’s plunder of Romanian forests, Doris pretends not to know but also gently reminds her that such deals couldn’t have passed without the approval of the Romanian government itself. “Citizens accept as well,” she adds.

In this peculiar sort of road film that leans into the fatigue of it, Jude’s acerbic, darkly comic commentary spans droll sketches on a particular strip of road bearing more death-indicating than its very length to green screen filmmaking in a portion that features the infamous director, Uwe Boll playing a critic-boxing meta-version of himself. The film leaps between these seemingly disjointed segments and becomes something baggy and sprawling in a manner typical of Jude’s work.

This overwhelmingly expansive film finally settles in its final act to concentrate on Ovidiu’s shooting for the work accident film. The frame mostly stays the same for this concluding stretch, the camera locked on Ovidiu with his family around him. Here, Jude’s writing is as abrasive and pointed as ever, intensely probing the specious language used by corporations as it practically batters Ovidiu’s family into implicitly acknowledging that his accident was entirely due to his oversight. In this razor-sharp, satiric peak, Radu Jude proves yet again he is one of our most uproariously, blisteringly incisive filmmakers, delivering a ceaselessly rich film on modernity, nationhood, and a populace caught in a blinded obeisance to the rest of Europe.

![It Comes at Night [2017]: An Excellent yet Empty A24 Horror](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/I1-768x316.jpg)

![Amiko [2018]: Fantasia Film Festival Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Amiko-2018-768x432.jpg)