Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) introduced one of the most iconic characters of Cinema in the form of Travis Bickle, brilliantly played by the great Robert De Niro. An alienated antihero for the age, Travis both fed off and fed into the perceived moral degeneration observed from the vantage point of the yellow cab he steers around the garbage-strewn streets of New York.

Scorsese’s waking dream of a film giddily explodes into violence as Travis’s pent-up psychotic rage forces its way out of his mind and into reality. Written by Paul Schrader and scored by Bernard Herrmann, Scorsese’s brooding, confrontational film has been widely recognized as a masterpiece that deservedly won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for four Academy Awards.

Taxi Driver is a film that operates on various levels—with its thematic and stylistic reflections, with its evocation of the political climate around the time of its release, which was characterized by the corruption of the Watergate scandal, the legacy of the Vietnam War, and the poor economic conditions in New York City. Here are ten films that are indispensable if you loved Taxi Driver, in no particular order of preference.

1. Pratidwandi (The Adversary) (1970)

Like Taxi Driver (1976), Pratidwandi is an ode to the battle between the man and the metropolis. It was New York for Travis Bickle, and here it was Kolkata for Siddhartha Chaudhuri. Adapted from Sunil Gangopadhyay’s work of the same name, this was Ray’s first film in the Calcutta trilogy. It revolves around Chaudhuri, a 25-year-old man living in Kolkata who has had to give up his medical studies after the unexpected death of his father.

He now lives with his widowed mother and two younger siblings. Siddhartha’s daily routine comprises walking the city’s streets looking for a job, appearing in interviews, and hanging out with two of his friends who are continuing their studies. After roaming around the city with the cruel sun over his head all day, he returns home at night, only to face the usual middle-class household problems.

Also Read: How Ray Explores The Rapidly Changing Facade of Calcutta in Pratidwandi (1970)

Frustrated beyond measure and still trying to keep his sanity, ethics, and decorum intact, Siddhartha is a man caught between a family that he cares for but cannot relate to anymore, a girl who is romantically interested in him but cannot commit to him because of her problems, and a city that seems hell-bent upon shoving him down to the ground every time he tries to locate it all by himself.

Provocative and daring, it was also stylistically experimental for Ray, featuring techniques inspired by the French New Wave, such as jump cuts, edgy framing, dream sequences, and sexual metaphors. Some of the experimental techniques that the film pioneered include photo-negative flashbacks and X-ray digressions. Several dream sequences remind one of Bergman’s Wild Strawberries. It is marvelously performed and gorgeously shot and remains one of’s very best works Ray.

2. Blow-Up (1966)

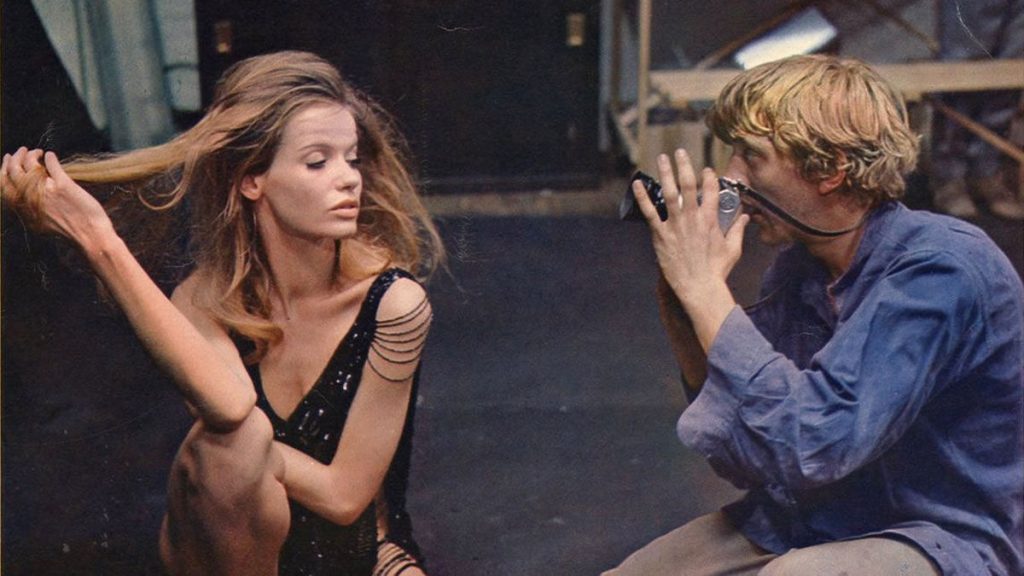

Blow-Up is about Thomas (David Hemmings), a photographer in 1960s London who accidentally takes a picture of murder. In the picture, the couple he has captured does not want to be seen, and in one picture, the woman (Vanessa Redgrave) seems to be looking, with concern, off to the woods where the man with the gun is hiding. Blow-Up was Michelangelo Antonioni’s first English feature, and it remains a film that resonates even today and is still capable of raising questions about the epistemology of Cinema while slyly recording a period that becomes so very enigmatic through a retrospective lens.

Also, Read: 10 Best Films of Federico Fellini

The title of the film becomes clear as Thomas repeatedly reworks, enlarges, and goes back to his negatives to locate the proof for something, obsessively searching for just any evidence of a possible occurrence that seems to have become increasingly elusive. Thereafter, Antonioni’s film becomes a study of the very nature of reality and how we deform the natural with interpretations and inflections.

Antonioni masterfully conceived the narrative progression, which indirectly tells us that viewing the film just as a thriller is pointless and certainly less enjoyable than soaking up the prevailing decadence and ennui. The person articulating truth with clarity seems almost incidental. That is the trick of clarity: the more clearly you state something, the less integral to that statement you appear to be.

So, Antonioni suggests that behind the image lies a deeper image (but still an image) “more faithful to reality” and then another beneath that and another. Underlying it all is yet another image (still a copy and not the thing itself) of “absolute” reality — a realm that one cannot access except “perhaps” through the decomposition of reality itself and all of its images.

3. Pick Pocket (1959)

Paul Schrader, who wrote the screenplay of Taxi Driver (1976), described Robert Bresson’s Pick Pocket as “an unmitigated masterpiece,” and the inspiration is evident in the similarities it shares with the 1959 classic and Taxi Driver in terms of its confessional narration and voyeuristic depiction of contemporary society. The film’s demure austerity moves toward a stark sense of minimalism, where Bresson insists on the subjective, limiting the narrative strictly towards what the loner hero, Michel (Martin Lassalle), sees, says, thinks, writes, and this is reinforced by his voice-over narration and his on screenwriting, and emphasized by a near-total absence of leading music.

Related To Taxi Driver (1976): Masculinity And Ignorance As Themes In Taxi Driver

His one passion is the art and crime of picking pockets, where he finds fear and excitement, exultation, and thrill- such feelings that otherwise do not have a residence in his life. Michel steals because it is the only act that makes him feel alive in a world becoming dead—not only dead to pleasure and unprogrammed emotions but, as later Bresson would make ever more explicit, organically dead. Theft reconnects Michel to the flow of life around him, from which he otherwise feels desperately isolated and which he perceives as pathetically limited in its possibilities. Pickpocket is at the center of things, a record of the expiration of humane feeling in the modern world, the impossibility of decency in a universe of greed.

4. The Merchant of Four Seasons (1972)

Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s pivotal film charts the decline of a self-destructive former policeman and war veteran by the name of Hans Hirschmüller, who is struggling to make ends meet for his family by working as a fruit vendor. Fassbinder wanted to make a film that could cater to a vast majority, and he put it like this- “The best thing I can think of would be to create a union between something as beautiful and wonderful as Hollywood films and a criticism of the status quo… That’s my dream, to make such a German film – beautiful and extravagant and fantastic, and nevertheless able to go against the existing order.”

The Merchant of Four Seasons does exactly that. It is as rigorous and layered a film in its indictment of a materialistic society as it is accessible in its morbid humor and honesty. Hans’s family scorns him and thinks of him as a disappointment. They shun him after the case of domestic abuse, siding with his wife while he still beckons her to come back. The only person on his side is his sister Anna (Hanna Schygulla), yet she has a minor role and is mostly ignored.

When we see the family on screen, they serve as eyes of disappointment with regard to Hans’s existence. The Merchant of Four Seasons tells a narrative of self-destruction, and it simultaneously unfolds as a tragedy about an ordinary man slowly killed by bourgeois expectations. It is a movie that reduces familial attachment to something transactional—people playing roles.

5. The Leopard (1963)

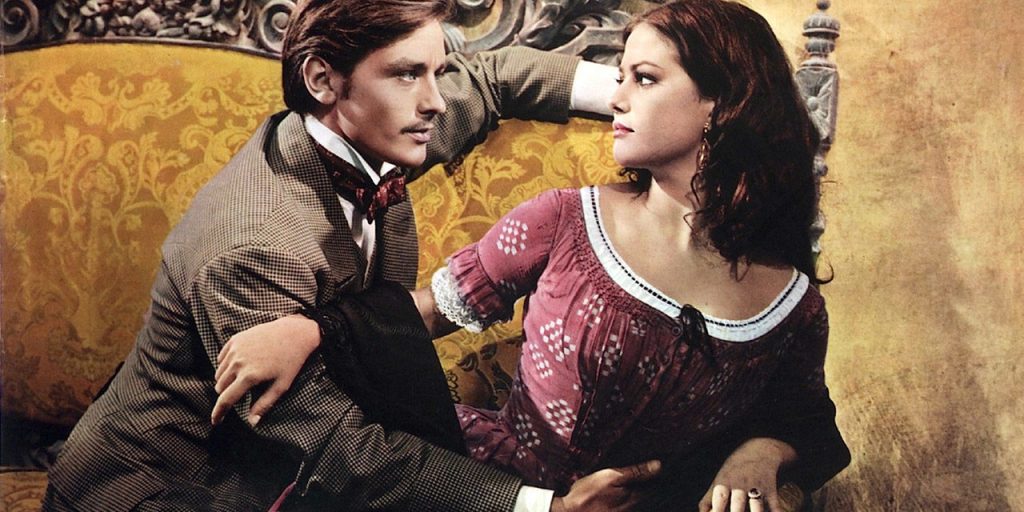

Scorsese has regarded Luchino Visconti’s Palme d’Or winning The Leopard as “a film that has become more and more important to me as the years have gone by.” This was to be Visconti’s most personal work, as the tale of an aging aristocrat who recognized the necessity for his social class to make way for the other classes, and the next generation struck a chord. The resulting film – an adaptation of the acclaimed novel by Lampedusa is extraordinary on many levels.

A lot of attention is paid to the dynamics between large groups of people gathered together – the various religious services, formal dinners, and, of course, the lavish ball, a much-celebrated sequence that takes up nearly the last third of the film. Visconti is less interested in driving the story than he is in creating the atmosphere and energy of the time and place. Visconti takes advantage of the Sicilian landscape and architecture to ensure that there is not a single frame that is not bursting with beauty.

Related To Taxi Driver (1976): The 10 Best Films of Martin Scorsese

The setting of The Leopard is not simply the background to the action but very much in the foreground. But these visual metaphors are key to understanding the dynamics of the society that takes its time to get into- here it is the political maneuvering within Sicilian society during the unification of Italy in the late 19th century, where the aristocracy had to make room for the new powerful middle class. This is explored at great length precisely because the film’s relaxed pace and long-running time allow the various issues and debates to be played out.

At the center of the grand historical events is the Prince, a man of great integrity and commitment. Although it is not apparent until the final ballroom sequence, the Prince has also resigned himself to his own mortality despite his strong attraction to Angelica. Nevertheless, the Prince does not take advantage of the situation and strongly encourages the marriage between her and his nephew, Tancredi Falconeri. In other words, the aging nobleman peacefully concedes to the younger generation and the middle classes both personally and politically. All these are maneuvered in masterful visual storytelling, making The Leopard a feast for the senses we bring to the cinema.

6. 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (1967)

“I wanted to include everything: sports, politics, even groceries. Everything should be put in a film,” wrote Godard about Two or Three Things. But particularly, Godard’s film tied down to these two ideas about how the social pressure exerted upon society, especially on women, by materialistic culture with its need to “keep up” combined with the effects that such power of materialism has on the living spaces of the urban and suburban areas around Paris.

In Two or Three Things we are presented with a very different filmmaker, offering a more genuinely radical and unflinching account of Western modernity. This is operated using a much more focused and small canvas, with regards to thematic treatment – with an important but still developing leftist commitment, with a notable increase in critical commentary about the USA’s global power, particularly its atrocities in Vietnam – but also a pointed and reflexive commentary on both Godard’s own filmmaking, as colored by a kind of artistic-existential crisis. Also important is how it manages to interrogate cinema’s particular role within the new mass media “reality”, which the film essays through a ruthless yet deeply fascinating lens.

There was a scene in Two or Three Things, I Know about Her where the camera closes in and lingers on the surface of a cup of coffee, a shot recreated by Scorsese in Taxi Driver (1976) as Travis drops an Alka-Seltzer into a glass of water before staring intently at the fizzing mixture. Scorsese had acknowledged the influence of Godard in his own style of film-making, and this was his tribute to the giant of the French New Wave.

7. The Wrong Man (1956)

In Hitchcock’s docudrama The Wrong Man, innocence is merely a probability, whereas guilt is the human condition. This is the crux through which the narrative operates- part thriller, part drama- about Manny Balestrero (Henry Fonda), a bass player who works in a music club. Despite some economic difficulties, his life is happy and rewarding: he has a beautiful wife, two kids who adore him, and a job that he loves. Everything changes the day in which he goes to his wife’s insurance company to ask for a loan: some of the employees are sure that he is the man who did a holdup at the office a few weeks before.

The same night, the police pick him up from his house to interrogate him and take him to some stores that had been robbed by the same man; apparently, everyone recognizes Manny as the person who did the holdups. When everything seems lost, the man who actually committed the crimes of which Manny is accused attempts a new robbery at a grocery store but is stopped, arrested, and positively identified as the holdup man. Manny is finally a free man, although it will take him and his family some time to recover from the trauma they experienced.

Related To Taxi Driver (1976): The Emotional Minefield of Alfred Hitchcock

In one strikingly powerful scene, the faces of the two characters are superimposed. This gives away the seemingly positivistic assumption by challenging the faith in the epistemological reliability of vision itself; it departs from a case of mistaken identity (what the victims of the robberies have seen leads them to false knowledge) and is resolved by a mere twist of fortune. What the superimposition does is give a visual dimension to the moment in which the lives of the two men cross, changing the fate of both, but it does not reveal their hidden nature nor any kind of absolute truth.

The Wrong Man centers around the possibility that miracles might happen and that cinema might be able to make them visible, if not intelligible. If we see the innocence in Manny’s face, it is because of our prior, extra-diegetic knowledge, but what does innocence in itself look like? Does innocence have a face? Does guilt?

8. 8½ (1963)

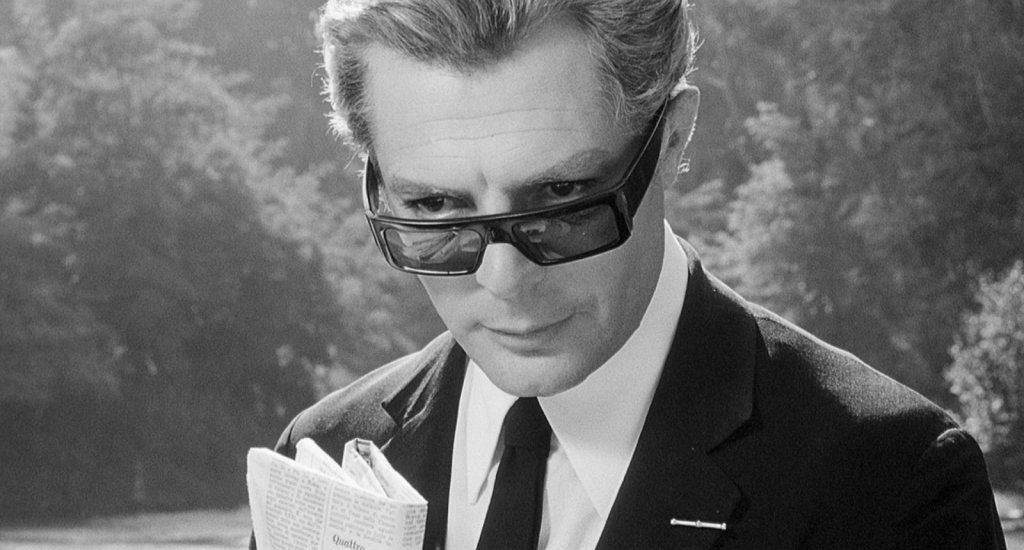

“81/2 has always been a touchstone for me,” Scorsese has acknowledged about Federico Fellini’s autobiographical odyssey, praising “the freedom, the sense of invention, the underlying rigor and the deep core of longing, the bewitching, physical pull of the camera movements and the compositions.”

The plot of 8 1/2 is almost incidental to Fellini’s purpose, which is to immerse the viewer into Guido Anselmi’s creative experience. It’s a surreal trip through the intense, emotional, and uncertain vortex of creativity. In Guido’s attempt to re-capture and harness artistic inspiration, he struggles with the limits of success and freedom. It’s a film full of symbolism that cries to be read but insists only on being felt and experienced.

Related To Taxi Driver (1976): 6 Great Federico Fellini Films

Before he approached 8 1/2, Fellini was responsible for seven-and-a-half films by his count: six full-length features, two shorts totaling one, and a co-director collaboration he counted as another half-film. As his self-referential title suggests, the Italian maestro’s film is about himself and filmmaking and the struggle to find a suitable subject for his latest project, his own eighth-and-a-half feature. Using a series of real-life parallels, his protagonist, Guido Anselmi, would experience the same crisis of inspiration that Fellini had experienced while initially conceiving 8 1/2, and through him, Fellini would create an unprecedented work of self-indulgent art.

9. The Searchers (1956)

John Wayne’s The Searchers has been more or less officially recognized as a great American classic. Scorsese regards how “Ford recognized something of his own loneliness in Ethan Edwards and that the character sparked something in him. It’s interesting to see how it dovetails with another troubled character from the same period.” He has also said how he reverts back to the iconic Western all the time, finding something to pause and reflect on in each viewing.

What becomes clear in the case of the film is how questioning the intention of The Searchers comes so naturally, as beyond its unequivocal beauty and dramatic intensity, there exists what appear to be incompatible narrative developments, symbolism, and thematic undercurrents signifying the end product as being at odds with itself. Ethan’s wandering, the elliptical journey, is contrary to the very trope of the West, which, prior to The Searchers, habitually followed a set narrative path forward, specifically in a westerly direction.

Related To Taxi Driver (1976): 10 Favorite Films of Martin Scorsese

Besides these thick narrative brushstrokes, there is an undercurrent in the way Ford rests his camera, using low angles to elevate his heroes and their backdrops, leaving the image stationary, which resultantly creates a sense of unrest on the landscape. Subversive in structure, the film orbits around its environment, broods over its emotions and offers no finality to Ethan Edwards’ conflict. It is by his confidence in his own vision that John Ford treats The Searchers like a traditional Hollywood Western and then masterfully subverts it into an uncommon human tragedy.

10. Contempt (1963)

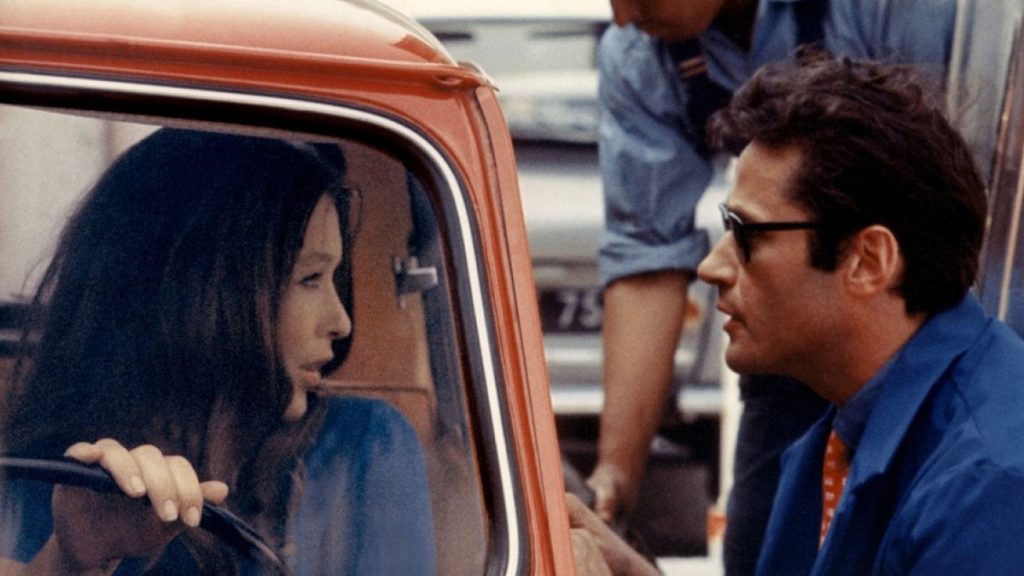

Contempt revolves around the disintegrating relationship between screenwriter Paul Javel (Michel Piccoli) and his wife, Camille (Brigitte Bardot). Like all of Godard’s films, Contempt is packed with ideas about the connections between life and art. Some resonate, others hit with the ping of self-consciousness. In Rome, Paul gets hired by American producer Jeremy Prokosch (Palance) to doctor the script for an international blockbuster based on Homer’s Odyssey, directed by Fritz Lang (Lang himself).

Shortly after Paul is hired, in the ruins of a once-bustling Italian studio (Cinecitta) that has just been sold, the writer insists that Camille ride in Prokosch’s red Alfa-Romeo to the producer’s villa outside Rome while he follows in a taxi; this flip gesture sparks the protracted on-again, off-again quarrel between Camille and Paul in their flat that takes up almost a third of the film–roughly half an hour out of 101 minutes.

Related To Taxi Driver (1976): Taxi Driver: An Existential Ride

The action shifts to Capri, where the film of the Odyssey is being shot, and the remainder of Contempt unfolds, charting the growing estrangement between the couple and Prokosch’s interest in an affair with Camille. Here, Godard manages to capture the fading of emotions- a plot that is able to trace the depletion of feelings in a marriage in a narrative that hides under its simplistic overtones a far more complex history.

Scorsese has acknowledged its impact and how profound an effect Godard’s film has had in his own style of filmmaking – “It’s a shattering portrait of a marriage going wrong, and it cuts very deep, especially during the lengthy and justifiably famous scene between Piccoli and Bardot in their apartment: even if you don’t know that Godard’s own marriage to Anna Karina was coming apart at the time, you can feel it in the action, the movement of the scenes, the interactions that stretch out so painfully but majestically, like a piece of tragic music.”