“G-21 Scenes from Gottsunda” is anchored in an inescapable conundrum mired in guilt and a unique tussle between abandonment and self-destructive loyalty. Many a time, envisioning a way out of an atmosphere that one knows is deeply detrimental and toxic may just be impossible for those stuck in it. Director Loran Batti grew up in such an environment, namely the ghetto of Gottsunda, one of Sweden’s most volatile neighborhoods. In it, generations of low-income communities find themselves inducted into a life of drug dealings and criminality. Youths from these families get sucked into this shady vortex and become so heavily entrenched in the nexus that there are only two exits: protracted jail time or getting killed.

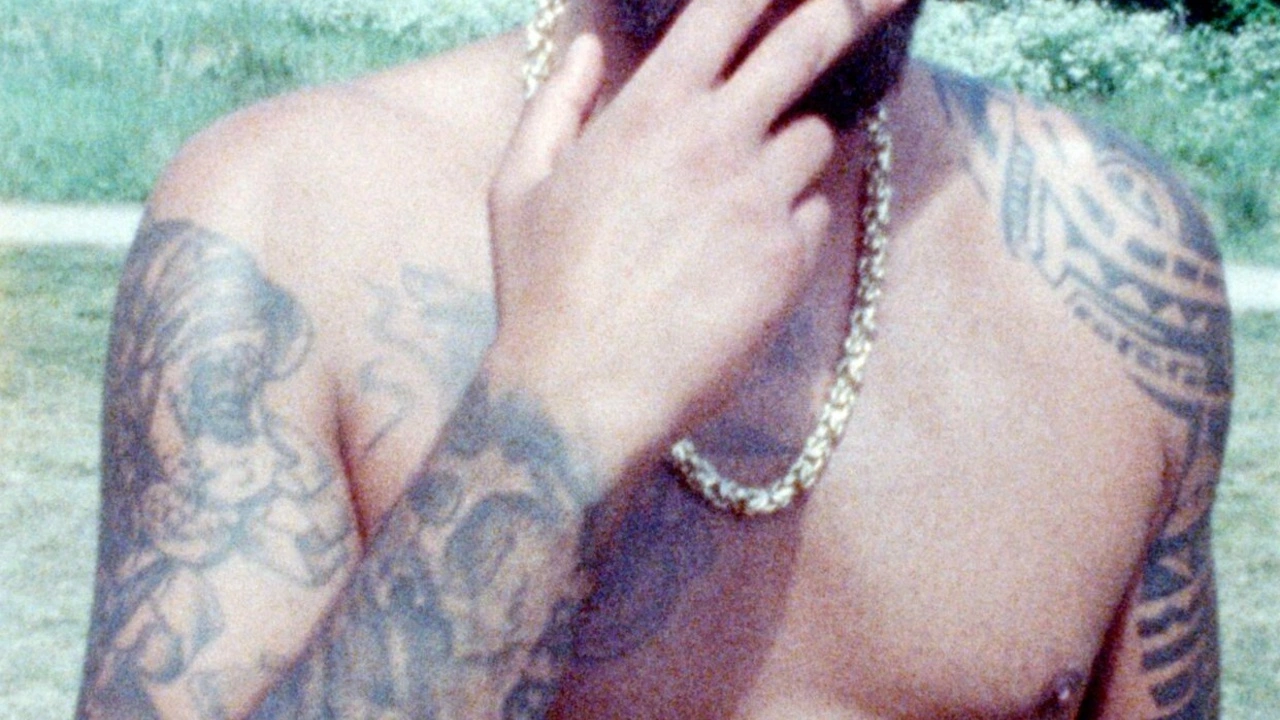

Loran spent a significant part of his growing-up years in Gottsunda. This is where he had forged the majority of his foundational friendships, as he stepped into adolescence. Unlike his friends, however, he held himself back from a full, active involvement in the circles of crime that are the inevitable ultimate rite of passage. What emerges in his conversations with an old friend, “the bear,” is that Loran chooses to keep a sort of distance while being in the bubble, eventually allowing him to narrowly scratch a way out of a mess that could have become a vicious cycle.

Loran doesn’t share specifics of when exactly and at what point of his adulthood he broke out and moved away from a life of crime that’d have defined him had he stayed back in Gottsunda. While I’d have preferred a little more clarity in this regard, Loran counters such expectations by emphasizing with gravitas and urgency the import of the essential decision that matters: staying in the hood or making that final call to leave. His friends have gotten themselves too embedded in a knot of complications to find their way out.

Importantly, the film underscores the acute self-awareness of those having chosen to remain in the infamous suburb. They aren’t retards, the film unequivocally states. Their rehabilitation into regular society and an ordinary life is armed with its own set of challenges. In order to get off the streets, which job giver would be willing to risk their hopes on them? Loran admits to the constant liminal state being from that particular bubble forces upon them. “We are in the middle”, they concede.

Having dramatically different experiences from the rest of society leads to its own peculiar isolation. Therefore integration or rather absorption into an everyday life replete with a safe, happy family is offset by several limitations. Being in that tight bubble brings incredible “eternal stress”; how do they even cast that off while trying to make new healthy relationships? Their difference is accentuated.

A friend nudges Loran to confess that he, too, felt special when he was a part of the gang. Going out on wild adventures and courting immense risk binds them together into one compact unit. The film also hints that most of the earlier tight bonding and looking out for each other has been replaced by a more fractious, splintering cluster of groups that have lost out on a sense of unity.

Loran keeps stressing his urgent investment in making the film, which he has been working on for more than five years. He hopes it will offer him closure and enable him to move on to the next chapter of his life. His vested interest in the film frustrates his mother and partner but he is certain he has to stick with it if he is to wholly leave Gottsunda for good. As much as the necessity of cutting himself off from that life is pronounced, Loran is also wistful for all those friendships he had to forfeit in the process.

The opening intertitle asserts that the film “takes no pride in being an objective record.” This crucial statement sets the tone and approach. Loran may try to venture with his probing camera into circles he can no longer access with perfect agency; most of the time, he is confronted with his own lack of control. A hangout with friends can swerve at any point into potential business meetings among gangsters. It’s a place he’d once been intimately habituated with but has now strayed far.

The passage of time has colored his perspective, and it takes the hardened insider old friend to brush the occasionally emerging rosy-eyed nostalgic flecks off his view. “G-21 scenes from Gottsunda” wends its way to a culminating conversation that left me in pieces. In a tide of irreparable sadness that washes over the viewer, rooted in a burst of confessional honesty, Loran Batti’s film inches toward profound, harrowing truth.

![Lost Girls [2020] Netflix Review – An unfocused take on police ignorance and a plea for justice](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Lost-Girls-Netflix-highonfilms-768x432.jpg)

![Love in the Villa [2022] Netflix Review: A Generic & Forgettable Rom-com That Romances a Heap of Cliches](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Love-in-the-Villa-2022-Netflix-768x512.jpg)

![Hridayam [2022] Review: Vineeth’s breezy love letter to a past with a lived-in feel](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Hridayam-2022-2-768x405.png)

![Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri [2017] – An Effective & Darkly Comic Outburst of Righteous Anger](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/cover2-1-768x512.jpg)