[A] certain kind of cinema exists only because a certain kind of state exists. — Saeed Mirza, Outlook for the Cinema.

Post the attacks of 9/11, Islam, from being a religious identity, had emerged as a political identity in America. Such a western construction of Muslim identity, propagated by the presidential speeches of George W. Bush, led to a binary between a ‘good’ Muslim and a ‘bad’ Muslim. Different agents in India carry out this project of Muslim identity construction, namely the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), on account of the rise of Hindutva politics in the country from the 1990s. This article uses the lens of films to examine how Muslim identity gets constructed by discursively analyzing them in terms of their release and consumption.

A narrative analysis of scenes and sequences within the films reveals how Bollywood, the Hindi film industry in India, has presented terrorism as a communal act by inevitably linking it to Islam and not as a criminal act. The narratives of the selected films also subscribe to Mahmood Mamdani’s (2005) claim, developed in the geo-political context of post-9/11 America, that “unless proved to be good, every Muslim is presumed to be bad” (Mamdani, 2005, p. 21). Virulently anti-Muslim sentiments are ideologically disseminated through the cultural production of such films. The selected films in my corpus for this research, in chronological order, are Sarfarosh (Fervour, Dir. John Matthew Matthan, 1999), Fanaa (Destroyed, Dir. Kunal Kohli, 2006), and Mulk (Nation, Dir. Anubhav Sinha, 2018).

The 1990s had been a decade of vast social and political unrest along communal lines in India, owing to the Babri Masjid conflict and its demolition on 6th December 1992 by the Kar Sevaks of Rashtriya Sevak Sangh (RSS), Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), and members of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). This was “coupled with the large-scale mobilization” of the upper caste Hindu upper-middle class and middle class as a part of the anti-Mandal commission protests (Kumar, 2016, p. 4). Amidst such growing tensions in the country, Bollywood filmmakers and producers had used cinema as an “ideological state apparatus” (Althusser, 2014, p. 75) to produce an image of the ‘Muslim other,’ or the ‘Muslim outsider.’ These films have portrayed the minority Muslims as a “metonymy of fear” (Kumar, 2016, p. 5). They ideologically function to instill a sense of fear, suspicion, and disbelief towards the entire community by projecting a figure of the Muslim who is inevitably linked with “terrorism, organized crime, and treason” and is a threat to the Hindu Rashtra (Hindu nation) (Kumar, 2016, p. 5).

Sarfarosh

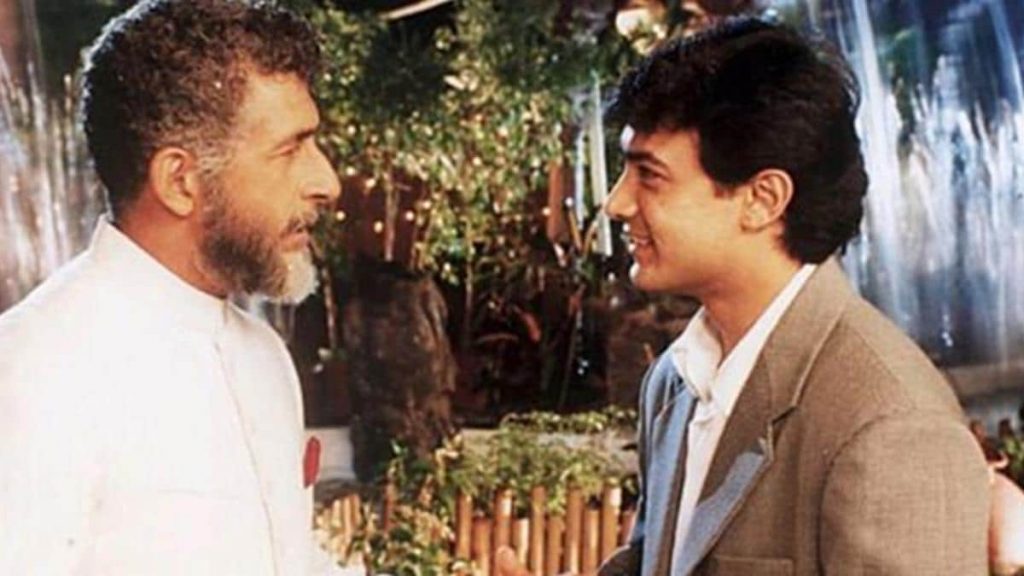

Othering: The narrative of Sarfarosh (1999), directed by John Matthew Matthan, has a Hindu savior of the nation, the Assistant Commissioner of Police, Ajay Singh Rathore (played by Aamir Khan), a ‘bad’ Muslim Ghazal singer, Gulfam Hassan, (played by Naseeruddin Shah), who is an undercover spy and terrorist from Pakistan, and lastly, an honest ‘good’ Muslim upright police officer, inspector Salim (played by Mukesh Rishi). Through the character of the ‘good’ Muslim, Salim, the film makes certain comments concerning India’s lower middle-class Muslim identity.

Salim was stripped off his duties, and removed from the investigation case of tracking down a terrorist responsible for causing a terror attack. Salim is an honest and upright police officer who is fully committed to his duties. He is equally loyal to the police force and has an extremely useful network of contacts which eventually helps to track down the terrorists by the end of the film. All these credentials and reasons seemed null and void to the Hindu-dominated upper echelons of the Mumbai Police. Salim was removed from the force solely because he was a Muslim, and so was the terrorist supplying the AK-47 rifles. Salim’s loyalty was assumed to be towards his community and his qaum (religion), not the police force and the nation. Thus, his fate was sealed, as he went on to be a victim of othering in his workplace, not because of any shortcomings in terms of his potential or achievements, but because of the qaum (religion) he was born into.

Insider-Outsider Dichotomy & Nation: The ‘word’ Salim has been used as an umbrella term for, and a signifier of, Muslim identity, whereby the Hindu Assistant Commissioner of Police, Ajay, reiterates the fact that he doesn’t need the help of any Muslim citizen to save his country from any form of attacks. Ironically, the narrative follows that Salim only turned out to be the greatest reason behind the Mumbai police’s success in seizing the AK-47 rifles and ultimately tracing and catching Gulfam Hassan red-handed. This is how Salim had to prove that he is a ‘good’ Muslim, by virtue of his contributions to preventing acts of terror by seizing the apparatuses of terror (AK-47 guns) and by successfully handling Gulfam Hassan to the Hindu ‘hero’ of the film, and the savior of the nation, Ajay, to be treated ‘normally’ in his workplace like his other Hindu colleagues, without a sense of disbelief, suspicion, or even fear.

Fanaa

Militancy or Terrorism?: Fanaa (2006), directed by Kunal Kohli, situates itself in Indian-occupied Kashmir, in the 2000s, after the rise of the militant insurgency in the region from 1989. Fanaa puts forward a quest for Azadi (independence), demanding an Azad Kashmir (independent Kashmir). It does so to ascribe an independent Kashmiri identity, free from occupation, through the efforts of a fictitious militant organization in the region named Independent Kashmir Front (IKF). Rehan Qadri (played by Aamir Khan), the ‘bad’ Muslim protagonist of the film, plays the role of a militant from Indian-occupied Kashmir, Srinagar, who is an all-important member of IKF. This reel organization has been fictionalized and incorporated into the narrative of Fanaa in the likeness of the real-life militant organization, Jammu & Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), founded in 1976 by Amanullah Khan, a militant from Kashmir who advocated for an autonomous Kashmir nation-state, free from both Indian and Pakistani occupation. While this quest for independence from the Indian occupation is seen as a militant movement in Kashmir, the same is labeled as terrorism in India. This is the reason why Rehan playing the role of a militant from IKF, has been projected as a terrorist in the film and, therefore, as a ‘bad’ Muslim by both the Indian media and the intelligence agencies.

Kashmiri Nationalism: Rehan’s wife, Zooni (played by Kajol), the ‘good’ Muslim in the film, got hold of a nuclear trigger and informed Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) about the same. Being a Kashmiri, Zooni’s ‘goodness’ has been portrayed as a signifier of her loyalty towards her colonizer, the Indian occupation. Zooni emerges as a ‘good’ Muslim at the end of the film, by shooting her husband, Rehan, who was fighting for their right to independence, and by handing over the trigger to RAW. Fanaa, through its narrative, evokes in the Kashmiri woman, a sense of nationalism and nationalistic duty towards her colonizer, which acts as a marker of her ‘goodness’.

Mulk

A Muslim’s Obligation: Mulk (2018), was released in India, four years after the right-wing Modi government came into power, and one year prior to the amendment of virulently anti-Muslim laws like the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC). Directed by Anubhav Sinha, the film situates itself in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, and raises the most important question to ascertain the identity claim of any ‘good’ Muslim in India through one of its dialogues: “How will you prove that you’re a good Muslim?” (Sinha, 2018, 1:49:26). While the earlier two films deal more or less with Bollywood’s characterization and representation of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Muslims, this film, being the concluding one in the sample, questions the obligation of each and every Muslim to prove that he/she is not ‘bad’.

Islamophobia: In the film, advocate Murad Ali Mohammad (played by Rishi Kapoor), the ‘good’ Muslim protagonist of the film, is a respected civilian, staying in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, with his joint family, for over 50 years. His nephew, Shahid Mohammad (played by Prateik Babbar), loses his life in a police encounter, after he joined hands with a terrorist named Mehfouz Alam, and caused a terror attack by planting a bomb in a bus.

After Shahid got killed, his entire family, including senior advocate Murad Ali Mohammad, was dragged to court with the allegation that the whole family was behind the Allahabad bus bomb blast, just because only one family member was involved in the attack. Murad Ali Mohammad’s daughter-in-law Aarti Mohammad (played by Taapsee Pannu) plays a lawyer in the film, who acts as his defense lawyer in the courtroom. The upper-caste Hindu opposition lawyer, Santosh Anand (played by Ashutosh Rana), on account of his virulently anti-Muslim stance based on prejudices against the minority community, accused the entire family of being involved in the practice of terrorism. Their ancestral house was labeled as a breeding ground for nurturing terrorists right from childhood, thereby framing the entire family as being traitors towards the ‘mulk’ (nation).

Santosh Anand, in the process of charging the entire family with such allegations, carefully and ideologically equated the crime of terrorism to Islam and Muslim identity. After such allegations, Murad Ali Mohammad woke up the next morning to find out that his Hindu neighbors had used black ink to inscribe the following words on the wall of his house: “Pakistan जाओ। Go to Pakistan.” (Go to Pakistan!) (Sinha, 2018, 1:14:14). Kumar (2016) rightly noted that the credibility of Muslims as the “rightful citizens of the Indian State is constantly in a state of incertitude” (Kumar, 2016, p. 16). It is assumed and perceived that their allegiance is directed towards Pakistan since it is an Islamic nation-state and not India. Such a worldview, thus, is very much concurrent with the dominant idea preached by the Hindutva discourse that “a Muslim’s faithfulness is primarily towards his or her religion, and not towards the country” (Kumar, 2016, p. 16).

Conclusion

The word Muslim stands for an ethnic, religious community, practicing Islam as a religion. ‘Good’ and ‘bad’, as prefixes to the word Muslim, add political significance to the community’s identity, indicating a shift from being a religious identity to a political one. This political dyad of a ‘good’ and a ‘bad’ Muslim denotes a split within the internal universe of Muslim identity into two political categories. This research has been conducted to take cognizance of how the Hindi film industry in India, Bollywood, has constructed Muslim identity on-screen by incorporating this dyad in the realm of representation since the 1990s with the rise of Hindutva politics in the country.

Despite the analysis over the years, two main commonalities in terms of the findings from this research stay intact in all the films over the years. Firstly, Bollywood’s portrayal of each and every terrorist as a Muslim. Secondly, the need and obligation of every ‘good’ Muslim to prove that they are not terrorists. Until and unless this is proved, they are treated with fear, doubt, and disbelief. This is how they become a victim of ‘othering’ in their workplace (Sarfarosh, 1999). Mamdani’s (2005) claim that “unless proved to be good, every Muslim is presumed to be bad”, is exemplified by the need of an innocent family to prove in court that they are not involved in an act of terror, just because only one member of the family was involved in it (Mulk, 2018). While a Hindu’s love for the Indian nation can never be questioned, a Muslim’s love and loyalty toward the nation are always under a scanner. Not only Murad Ali Mohammad from Mulk but also the Kashmiri woman, Zooni from Fanaa had to prove her loyalty towards their colonizer by killing her husband, who was a militant dedicated to the Azaadi (independence) of Kashmir from Indian occupation.

References

- Althusser, L. (2014). On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. Verso.

- Kohli, K. (2006). Fanaa. Aditya Chopra.

- Kumar, S. (2016). Metonymies of Fear: Islamophobia and the Making of Muslim Identity in Hindi Cinema. Society And Culture In South Asia, 2(2), pp. 1-23.

- Mamdani, M. (2005). GOOD MUSLIM, BAD MUSLIM: America, the Cold War and the Roots of Terror. Three Leaves Press.

- Matthan, J. (1999). Sarfarsoh. John Matthew Matthan.

- Mirza, S. (1979). Outlook for the Cinema. Social Scientist, 8(5/6), pp. 121-125.

- Sinha, A. (2018). Mulk. Anubhav Sinha & Deepak Mukut.