History is brimming with untold stories and forgotten heroes—a catalog cinema is slowly chipping away at between Marvel releases, sometimes for lack of original ideas (or lack of a guaranteed audience to watch the ideas without the holy promise of fanservice) and sometimes, as is the case with “Joy” because it’s a story that needs to be told.

Director Ben Taylor is the perfect man to tell such a tale, intrinsically linked to this incredible true story of IVF treatment due to the fact his own children were made possible through such medical breakthroughs. Many viewers will likely know—consciously or otherwise—friends, family members, colleagues, or acquaintances who have some association with IVF (In vitro fertilization), or even themselves be born via a “test tube.” Miraculous as the science is that’s unburdened thousands—millions—of childless women across the world, it wasn’t all rainbows and butterflies for those involved. And not just because science is, well, really hard.

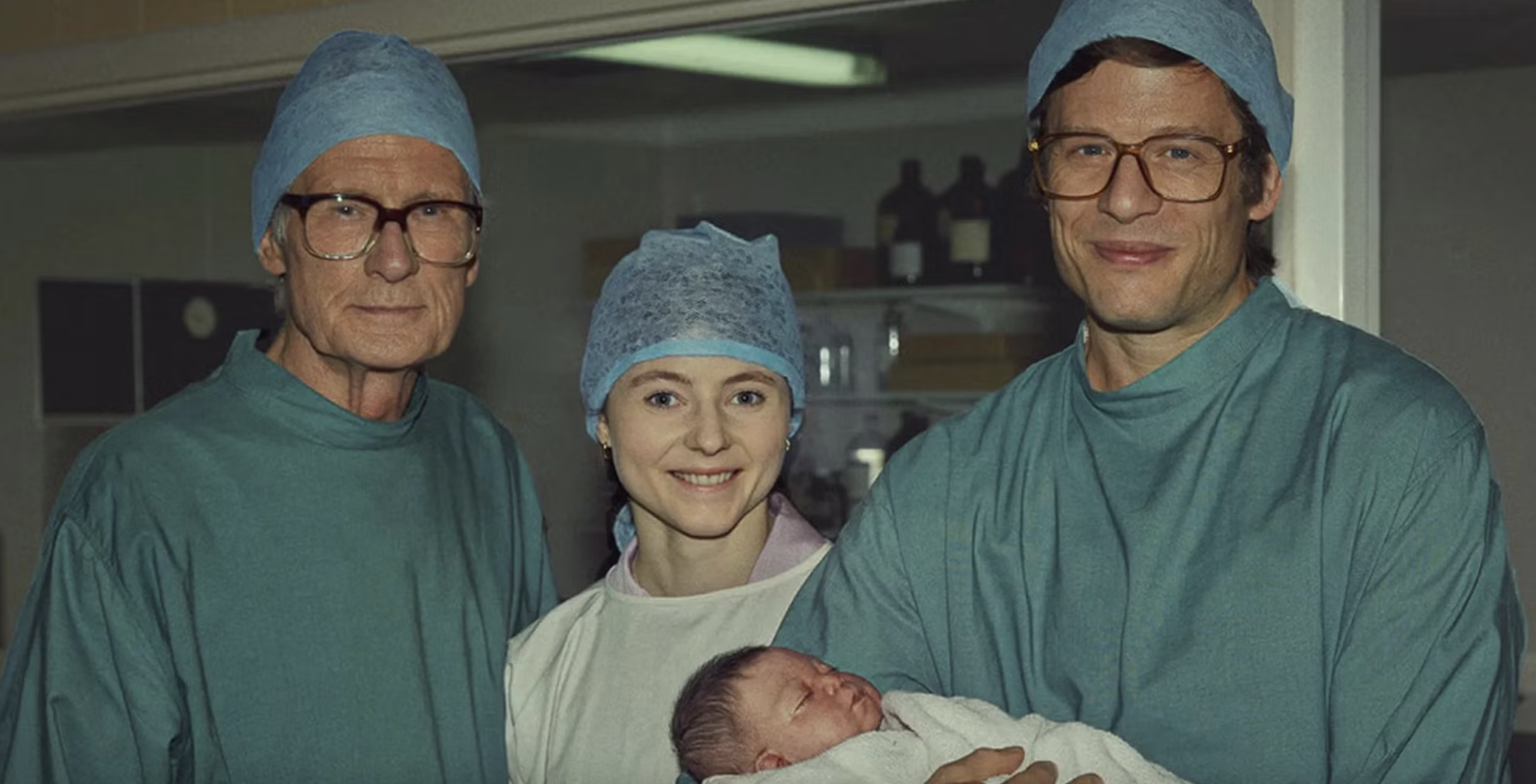

Jean Purdy (Thomasin McKenzie), Robert Edwards (James Norton), and Patrick Steptoe (Bill Nighy) faced an onslaught of criticism from every direction when developing IVF, slandered by the media and sent threatening mail by churchgoers for their audacity to stick their fingers in the pie of life. Being crowned a baby killer (the three were also pro-abortionists) was not the outcome the team had in mind when trying to cure infertility—it was quite the inverse. But despite screaming protestors and nicknames like Mr. and Mrs. Frankenstein (“It’s Doctor Frankenstein,” Robert corrects, embracing the derogatory sobriquets until they’re emptied of power), the trio pushed through the sleepless nights and day-long commutes to cure those who don’t meet the “biological and social expectation” of motherhood, however much they yearn to.

Robert planted the IVF seed in the 1960s, researching in the lab and recruiting nurse Jean and surgeon Patrick to water and trim the saplings until life was harvested in 1978. It was a kernel of an idea that would pop into the existence of a million “test tube babies,” the first of which was Louise Joy Brown. Louise, who walked the red carpet alongside the stars for Joy’s world premiere at the BFI London Film Festival, was a true miracle baby, tucked away in Oldham General Hospital, Manchester. Jean and Robert swung back and forth between Manchester and Cambridge to make her birth possible, afforded nothing by the government but a shabby basement hospital room with missing windows and mothballs to get there.

Joy is an appropriate middle name for Louise, as that’s what Jean, Robert, and Patrick’s pioneering work made possible nationwide, against all odds—biologically, socially, financially, or otherwise. Jean—who was disowned by her mother and religion, tragically unable to conceive herself (even with IVF) or survive cancer—is the focal point of Taylor’s cozily lit biopic, sacrificing her life with little reward and learning how to connect to the brave women who volunteered their bodies as people rather than experiments.

Not only does Jean Purdy deserve her name on the honorary plaque (the closing credits reveal she was posthumously added like an afterthought in 2015, which was basically yesterday) she arguably deserves to be at the top. The minute Jean (briefly) left the trial, the whole project collapsed, a sign reading Sorry, We’re Closed swinging on the door handle of IVF until she returned to blow dust off the lab flasks. As we experience the story through Jean’s stockings, giving Joy the grounded human touch that Jean herself learns to extend to the IVF volunteers, we pause when she pauses—when a dying mother, hate mail, denigrating community, and media frenzy become too much and arrest IVF development. Luckily, Jean gets over the seven-year itch and rounds the crew back up again, and it’s through this that Taylor demonstrates her crucial role in history.

Taylor doesn’t just present one side of the coin but touches (ever so lightly) on the complexities of shifting cultural mindsets and Jean’s own conversion from pro-IVF in the context of being pro-life, to just pro-choice. Indeed, choice is at the crux of this entire movie, as well as the movement that made it possible. It makes sense for IVF to be born (literally) at the turn of a revolutionary decade—a time of the contraceptive pill, mini skirts, and acidheads. Even if “Joy” itself isn’t so ecstatically grand and groovy to watch. During the ’60s, women were jimmying the lock that shackled them to motherhood at the kitchen sink, snatching at the chance to choose whether they wanted careers, conception, or safe, legal abortions. IVF helped make this choice available to them.

Jean, Robert, and Patrick—alongside pro-choice no-nonsense nurse Muriel (Tanya Moodie), and the women who enlisted for clinical trials—form a dauntless libertarian brigade in “Joy,” smashing through the rubric of conservative Christian society. Joy’s characters are warm, buttoned-up, good-standing members of society; oh-so-Blighty (the first on-screen word is, after all, “bugger it,”) and living off tea and biscuits. Therefore, we can’t expect a dazzling all-out spectacle of mind-bending cinematic experimentation. It simply wouldn’t fit the story, which is comprised of real people, humble and at home in the Church bake sale (well, until Jean is excommunicated for “playing God”).

The usual structure of a biographical drama is to be expected from Taylor’s directorial debut, and though it won’t earn “Joy” a spot on the Oscar-winners list, the country lanes, hangover-from-the-forties furniture, and knitted cardigans slide on like a glove between moments of cathartic conversation. “Joy” shakes hands with the crowds rather than the avant-garde cinephiles, palatable and easy to watch (though it definitely wasn’t easy to live, no matter which side of the surgeon’s knife you were on) but as a result, getting an important story out there. “Joy” pinches the patriotic heartstrings of Brits, leaving us inspired, proud, and bittersweet in our remembrance of the past. It’s no Kubrick, but sometimes we just need a little lamplit joy.

![A Spike Lee Joint: School Daze [1988]](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/School-Daze-Spike-Lee-1-768x432.jpg)

![Review That Jack Wrote [2018]: ‘MAMI’ Review of The House that Jack Built](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/house_that_jack_built_director_lars_von_trier_header_1050_591_81_s_c1-768x432.jpg)