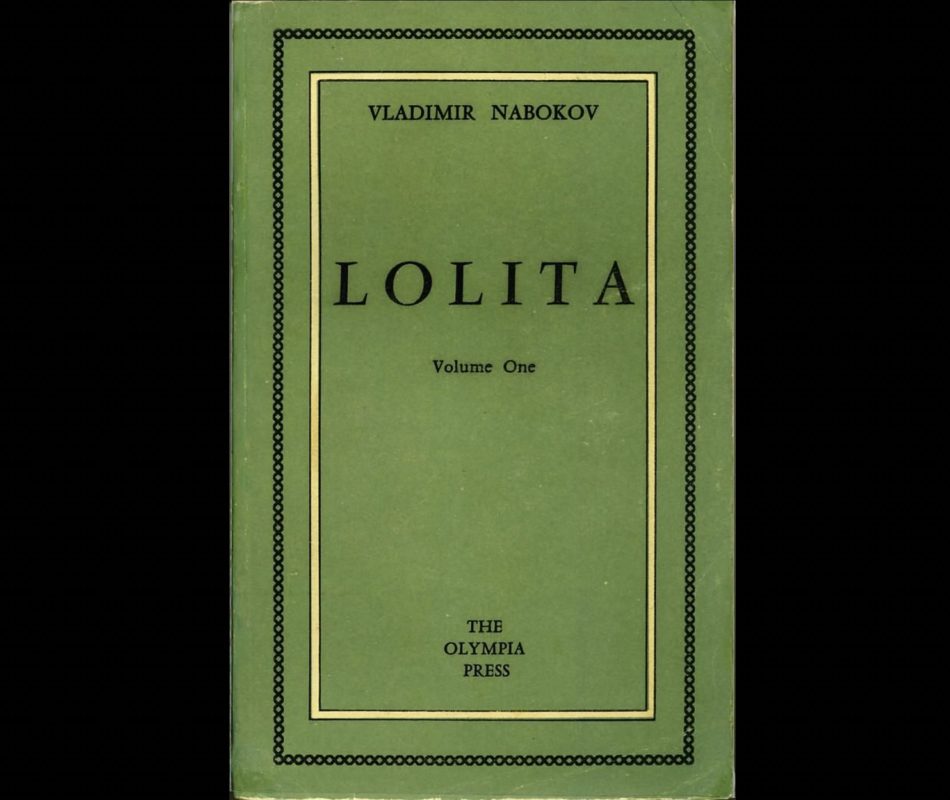

Since the mid-20th century, cinema has been haunted by the figure of the nymphet, a sexually precocious, often underage girl, constructed not as a real child but as a projection of adult male fantasy. This figure, most famously canonised in Vladimir Nabokov’s most famous and controversial novel, “Lolita” (1955), gave rise to “nymphetmania”: an enduring cultural and cinematic obsession with the forbidden allure of the girl-child.

In Nabokov’s own words, a “nymphet” is not defined merely by age, but by her perceived power over the older male gaze – “maidens who, to certain bewitched travellers, twice or many times older than they, reveal their true nature, which is not human, but nymphic.” She exists not independently, but only in relation to the man who is bewitched by her. This dynamic, where the girl becomes a mirror for male longing, loss, and madness, has since become a cinematic trope, repeated and reimagined across decades and genres.

In the classical mythological sense, the nymph was a nature spirit: enchanting, elusive, and not entirely mortal. She was not a child, nor fully human, and thus her seductiveness was often framed as both divine and dangerous. Translated into modern literature and film, the nymphet inherits this paradox. She is coded as innocent yet sexually aware, juvenile yet emotionally manipulative, a contradiction born not of her own subjectivity, but of the male desire that imagines her into being.

In cinema, the nymphet functions as a visual paradox: she exists only in relation to adult longing, framed not as a person with agency or interiority but as an enigmatic cipher through which male characters, and, by extension, male spectators, confront their fantasies, failings, and fears. What emerges from decades of cinematic exploration is not a girl, but a construct: a hybrid of erotic innocence, psychological projection, and narrative convenience. Her sexuality is both denied and exaggerated, her power both feared and fetishised.

Whether cast as the manipulative child-woman, the silent muse, the traumatised victim, or the morally ambiguous seductress, the nymphet is consistently shaped by the gaze that desires her. The nymphet does not and cannot exist outside the male gaze. As explored in Edda Margeson’s article “Tracing Lolita,” she is not a girl but a projection: a “Presence,” as Faulkner writes, pursued unto self-destruction. In this dynamic, the male character is not only the predator but also the victim of his own desires. The nymphet remains forever unattainable because she never really existed in the first place.

This gaze, what feminist theorist Laura Mulvey famously termed the male gaze, operates as a structuring force in mainstream cinema, positioning women and girls as objects of visual and erotic pleasure rather than as agents of their own stories. In Mulvey’s seminal 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” she argues that women are often “looked at and displayed with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact.”

Nowhere is this more disturbingly evident than in films centered on the figure of the nymphet, whose very presence on screen calls into question the ethics of spectatorship, power, and desire. Ultimately, this is not just a study of the nymphet, but of the camera that imagines her, the culture that consumes her, and the voices that have begun, at last, to speak back.

From Stanley Kubrick’s “Lolita” (1962) and Louis Malle’s “Pretty Baby” (1978) to more recent films like “Fish Tank” (2009) and “The Diary of a Teenage Girl” (2015), cinema has repeatedly circled back to this figure, reshaping her according to changing cultural mores, but rarely letting go of the central fantasy. From the colonial eroticism of “The Lover” (1992) to the gothic psychosexualism of “Stoker” (2013), the trope of the nymphet has evolved, morphed, and resurfaced in multiple forms across different genres, cultures, and cinematic traditions.

These films tend to oscillate between eroticization and critique, between enchantment and condemnation. In some, the nymphet is a manipulative femme fatale in miniature (“Poison Ivy,” “Stoker”); in others, she becomes a sacrificial muse, fuelling the male protagonist’s existential or midlife crisis (“American Beauty,” “Lost in Translation”).

In recent decades, especially from the early 2000s onward, a number of women filmmakers have begun to reclaim, revise, or entirely dismantle the trope. Films like “Thirteen” (2003), “Fish Tank” (2009), “Palo Alto” (2013), “The Diary of a Teenage Girl” (2015), and “The Tale” (2018) shift the lens inward, challenging the voyeuristic structures, centering the girl’s subjectivity and interiority rather than her sexual legibility. These counter-narratives do not merely critique the trope, they expose the structural violence behind its construction, offering alternative visions of girlhood that are messy, fragmented, and defiantly uncommodifiable.

This write-up explores how cinema has taken up and reconfigured the nymphet figure, what we might now call nymphetmania, by examining a constellation of films from the mid-twentieth century to the 2010s. It also attempts a thematic and critical unpacking of the trope, engaging with feminist film theory, especially Laura Mulvey’s theory of the male gaze, and more recent counter-narratives from women directors.

I. Origins and Canonical Roots: Lolita and the Birth of the Nymphet

The cinematic obsession with the nymphet, a girl who is both child and sexual object, finds its most explicit origin in the cultural afterlife of Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lolita” (1955). Though Nabokov’s novel is a dense, metafictional critique of obsession and manipulation, it inadvertently gave rise to one of the most persistently provocative, or as ethically fraught tropes in film history. The term “nymphet,” coined by the novel’s unreliable narrator Humbert Humbert, refers to a certain kind of underage girl: not merely young, but imbued with an erotic aura visible only to the adult male eye.

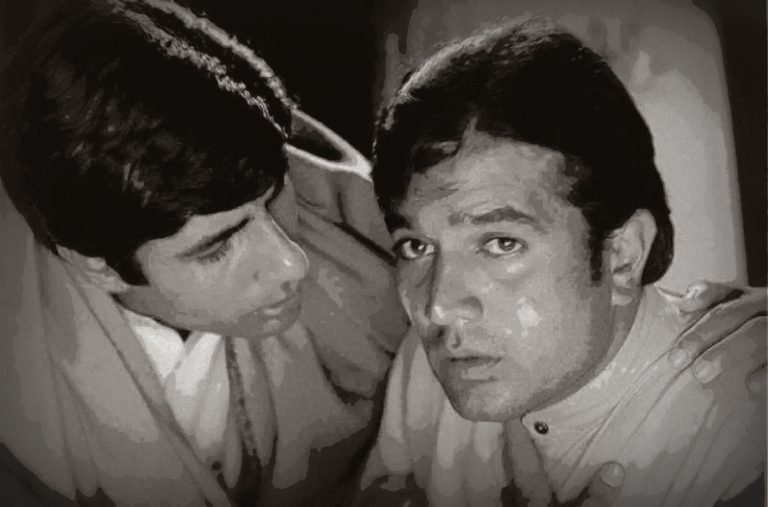

Cinema seized upon this figure with both fascination and danger. Stanley Kubrick’s “Lolita” (1962) and Adrian Lyne’s more explicit remake (1997) are cornerstone texts in cinematic nymphetmania. Both adaptations of Nabokov’s novel offer a troubling look into the mind of an adult man sexually obsessed with a young girl. Stanley Kubrick’s “Lolita” (1962), the first major adaptation of Nabokov’s novel, marked a turning point.

Constrained by the Production Code’s restrictions on sexual content and depictions of underage relationships, Kubrick opted for subtlety and innuendo. Yet, in avoiding explicitness, the film leaned into stylised suggestion: Sue Lyon’s portrayal of Lolita, complete with heart-shaped sunglasses, bare shoulders, and sultry glances, became a cultural icon, immortalising the image of the sexualized child in pop culture. Rather than critically unpacking Humbert’s delusions, the film invited the viewer to become complicit in his gaze.

Kubrick’s film was widely praised for its restraint and aesthetic control, but feminist critics have long noted how the cinematic form, unlike literature, inevitably visualizes what the novel ironizes. In the transition from text to screen, the distance between author, narrator, and character collapsed, and the critical irony of Nabokov’s work gave way to the sensory pleasures of watching. What the novel framed as a psychological and moral horror became, in film, a provocative tableau. In this shift, “Lolita” helped inaugurate an entire cinematic tradition: one that fetishizes the girl under the guise of art, irony, or tragedy.

This legacy continued and intensified with Adrian Lyne’s 1997 adaptation of “Lolita,” a film that leaned heavily into visual sensuality and atmosphere. With its golden lighting, slow pans, and voiceover narration, Lyne’s “Lolita” turned the nymphet into a full-blown aesthetic spectacle. The girl (played by Dominique Swain) is frequently framed through Humbert’s fantasy: her legs, her mouth, her body half-obscured and half-revealed, caught in moments of staged innocence or exaggerated flirtation. Though the film gestures at psychological depth and moral ambiguity, it ultimately replicates the very dynamic it might critique, making the viewer complicit in Humbert’s gaze while claiming to disapprove of it.

These two adaptations – Kubrick’s suggestive restraint and Lyne’s erotic stylization – cemented “Lolita” as a cinematic touchstone, shaping not only how the character of the nymphet was portrayed but how audiences were taught to look at her. What began as a fictional critique of male delusion thus evolved into a cinematic language of longing, a visual grammar for stylizing underage femininity as erotic spectacle.

The birth of the nymphet in cinema is not simply a borrowing from literature, but a re-encoding: one that strips away narrative irony and replaces it with seductive framing, lush cinematography, and affective manipulation. As such, the figure of the nymphet becomes not only a product of narrative but a creation of the camera, a function of framing, lighting, and montage, shaped by the structures of cinematic desire.

II. Eroticised Innocence: The Nymphet in 1970s–1990s Cinema

If “Lolita” planted the cinematic seed, the following decades witnessed its proliferation, particularly in the sexually and aesthetically charged landscape of 1970s to 1990s cinema. During this period, the nymphet figure was reinterpreted, stylized, and increasingly eroticized, often under the guise of artistic daring, psychological realism, or social critique. These decades marked a turning point: the nymphet was no longer a literary anomaly but a cinematic type – glamorous, dangerous, and profitable.

1. Pretty Baby (1978): The Child As Spectacle

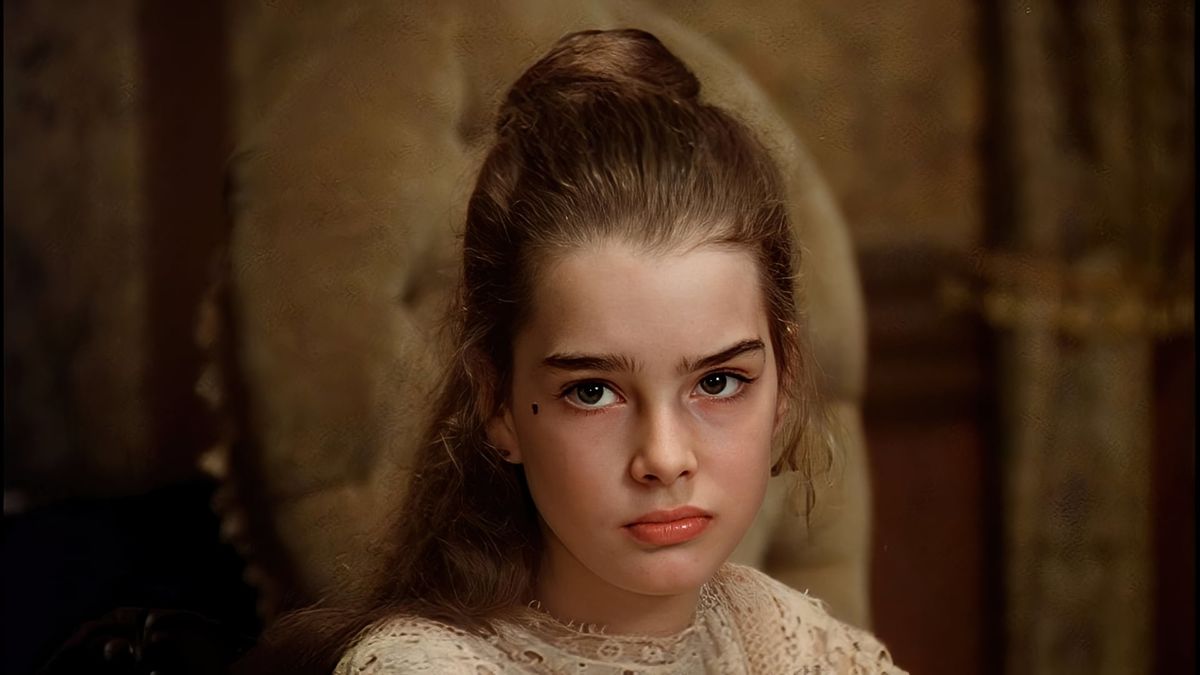

Louis Malle’s “Pretty Baby” ignited controversy for its depiction of a 12-year-old girl, Violet (Brooke Shields), growing up in a New Orleans brothel in the early 20th century. She is groomed into sex work under the indifferent gaze of the adults around her. Though framed as a historical coming-of-age tale, the film frequently lingers on Violet’s body and face, oscillating between pathos and voyeurism. The camera aestheticizes her innocence, often juxtaposed with adult eroticism, creating a visual dissonance that unsettles, but also titillates. Shields’ performance, directed and posed rather than acted, became emblematic of the industry’s willingness to exploit the image of the child while pretending to mourn her lost innocence. Feminist critics were quick to point out the film’s troubling ambiguity: was it a critique of child sexualization, or a carefully disguised indulgence in it?

2. The Lover (1992): Colonial Desire And The Eroticized Girl

Jean-Jacques Annaud’s “The Lover,” based on Marguerite Duras’ autobiographical novel, tells the story of a 15-year-old French girl (Jane March) in 1920s colonial Vietnam who enters into a sexual relationship with a wealthy Chinese man (Tony Leung Ka-fai). The film is drenched in slow motion, golden hues, and languid eroticism. While Duras’ text is introspective and ambivalent, the film leans into sensuality, transforming a narrative of colonial trauma and racialized desire into an aestheticized love story. The girl is shown as both a sexual agent and a symbol – both desiring and desired, but always captured through the lens of exoticism, whiteness, and male fantasy.

You Should Also Read: The 10 Best May-December Romance Movies

The girl is filmed with soft erotic intensity, her pale skin, bare limbs, and schoolgirl uniform becoming emblems of fragile yet dangerous innocence. She is both narrator and narrated, agent and object, speaking her desire in voiceover while her body is repeatedly framed in silence. The man, the colonial “Other,” by contrast, is rendered as both powerful and emasculated, trapped by his cultural position and his uncontrollable desire for a girl who represents both Europe and erotic ruin.

Their relationship, while consensual in surface terms, is shaped by vast imbalances of age, race, class, and colonial history. The nymphet in “The Lover” becomes a muse of softcore colonial erotica, a figure onto whom fantasies of decadence, decay, and doomed desire are projected. The girl’s body is aestheticized to the point of abstraction; her emotional world remains largely inaccessible.

3. American Beauty (1999): The Nymphet As Midlife Fantasy

In Sam Mendes’ “American Beauty,” the nymphet trope is recontextualized within the existential malaise of American suburbia. Kevin Spacey’s Lester Burnham, a disillusioned, emasculated office worker in the throes of a midlife crisis, becomes erotically fixated on his teenage daughter’s best friend, Angela (Mena Suvari). What begins as a comic premise a middle-aged man reclaims his masculinity, gradually curdles into something darker: the projection of male fantasy onto the body of a child.

Angela is the quintessential nymphet, not because she possesses any true sexual power, but because Lester imagines her that way. She appears to him in dreamlike fantasy sequences, bathed in rose petals, moving in slow motion, smiling coyly in shimmering light. These scenes do not depict Angela as she is, but as Lester sees her: idealized, eroticized, and stripped of interiority. The film uses these visual cues deliberately, drawing attention to the constructedness of Lester’s desire. In this way, “American Beauty” flirts with self-awareness. But the flirtation is uneasy.

Though the film attempts to critique Lester’s delusion and ethical collapse, it also risks seducing the viewer into sharing his gaze. Angela is rarely granted the narrative agency to resist or redefine herself. Her vulnerability, revealed only late in the film, is a twist, not a truth the film nurtures throughout. By then, she has already functioned as muse, temptation, and crisis point for Lester’s unraveling masculinity. Even her eventual refusal, “I’m a virgin”, serves more as a moral awakening for him than a recovery of her voice.

From a feminist standpoint, “American Beauty” exposes the extent to which girlhood in cinema is often used as a screen for male projection. Angela is less a character than a symptom of Lester’s arrested desire, of suburban stagnation, of repressed sexuality dressed up as epiphany. Her body becomes the battleground on which the film stages its cultural critique of masculinity, family, and consumerism. Ultimately, “American Beauty” is not about Angela, it is about Lester’s crisis, and by extension, about a culture that routinely turns girls into mirrors for male dissatisfaction. The film reveals how the nymphet trope persists not merely in the pornographic or the explicit but in the middle-class imagination, cloaked in irony, beauty, and tragic self-realization.

III. The Dangerous Nymphet: From Object Of Desire To Femme Fatale

While the early cinematic nymphet, as seen in “Lolita” or “Pretty Baby,” was often characterized by a passive eroticism, more muse than manipulator, the 1990s and 2000s ushered in a darker variant: the dangerous nymphet. No longer simply the object of adult male longing, this version of the trope is imbued with agency, cunning, and even menace. She seduces deliberately, disrupts domestic life, and manipulates power. Yet her apparent autonomy is a double-edged sword: the girl may now act, but she does so within a narrative architecture that ultimately punishes her for her transgressions. Her “danger” is framed not as liberation, but as a threat.

Related Read: Finding Beauty in the Absurd: An Existential Reading of ‘American Beauty’ (1999)

4. Poison Ivy (1992): The Dangerous Lolita In A Femme Fatale Key

“Poison Ivy” (1992), directed by Katt Shea, is one of the most stylized and provocative entries in the lineage of post-Lolita cinema. Starring Drew Barrymore as Ivy, a street-smart, hypersexual teenage girl who infiltrates a wealthy suburban family and seduces the father, the film occupies an uneasy space between erotic thriller and teenage melodrama. It reframes the nymphet not as a passive object of desire but as a cunning, active agent, though one still filtered through patriarchal paranoia and sexual fantasy.

Ivy is portrayed as a teenage femme fatale: manipulative, sexually confident, and emotionally unstable. Her allure lies in her transgressive charisma, she wears school uniforms with a slouch, delivers sultry one-liners, and gazes directly back at the camera. Yet her agency is ultimately illusory. Ivy’s desire is choreographed to both attract and punish; her sexuality is empowered only insofar as it threatens the status quo, and is thus destroyed by the narrative’s end. She is a disruption, not a subject: a catalyst for the breakdown of the bourgeois family, but not a character with psychological or moral depth.

Unlike Nabokov’s “Lolita,” whose ambiguity resides in the reader’s ability to discern narrative manipulation, “Poison Ivy” is unapologetically literal. It weaponizes the trope of the “dangerous girl” to stage a clash between youthful eroticism and adult repression. The mother (Cheryl Ladd), physically ailing and emotionally absent, is contrasted with Ivy’s vitality and seduction. The father, predictably, falls. Yet the film also invites a certain identification with Ivy, especially for young female viewers who may see in her a rebellion against stifling norms of femininity, even as the film punishes her for transgressing them.

Visually, the film indulges in the soft-core aesthetics of early ’90s thrillers: saturated lighting, steamy rain-soaked scenes, voyeuristic camera angles. Ivy’s body is not just observed—it is stylized, framed, and fetishized. Despite being directed by a woman, “Poison Ivy” does little to escape the visual codes of male desire. In retrospect, “Poison Ivy” marks a turning point in the evolution of the nymphet trope, it signals a shift from victim to vixen, from helpless child to seductive threat. But this transformation is largely aesthetic, not structural. Ivy may speak, seduce, and scheme, but she is still created for the gaze, not in defiance of it.

5. Bitter Moon (1992): The Nymphic Erotics Of Obsession

Roman Polanski’s “Bitter Moon” is a baroque, psychosexual chamber piece about lust, degradation, and narrative possession. Though not explicitly centered on a “nymphet” in the strict sense, the film functions as an adult extension of the Lolita paradigm, reframing the trope not through the lens of adolescence, but through the intoxicating and destructive allure of the idealized feminine. Mimi (Emmanuelle Seigner) becomes the erotic object of a much older man’s obsession, first as fantasy, then as humiliation, and finally as revenge. She may not be a child, but she is infantilized, fetishized, and shaped entirely through male perception. In this way, “Bitter Moon” becomes a mature and deeply troubling study in how the nymphet fantasy mutates into adult pathology.

Told primarily through the flashback-laced narration of Oscar (Peter Coyote), an aging, wheelchair using American writer living in Paris, the film recounts the torrid and increasingly sadomasochistic affair he once had with Mimi. Oscar relives and re-narrates Mimi, reducing her to a sequence of erotic episodes: playful nymphet, sexual muse, submissive servant, and finally, sadistic avenger. Seigner’s performance as Mimi is one of calculated seduction and theatrical excess.

7 Erotic Thrillers From The 90s That Will Keep You Hooked Like ‘Babygirl’

She is stylized to the point of unreality: her childish pigtails, sailor dresses, high-pitched voice, and coquettish mannerisms in the early part of the film evoke a constructed innocence that echoes Lolita’s visual grammar. Oscar’s attraction is rooted not only in her sexuality, but in her performance of youth, her gamine quality, her spontaneity, her perceived malleability. She is not a character, but a fantasy being written in real time. “Bitter Moon” is thus a brutal meditation on erotic obsession, power, and narrative ownership. It shows that even when the nymphet becomes a woman, she remains, above all, a story being told, and never quite her own.

6. Chloe (2009): The Constructed Nymphet

Atom Egoyan’s “Chloe” offers a more psychologically complex version of the dangerous nymphet, where she is reimagined through the lens of manipulation, performance, and maternal projection. Amanda Seyfried plays Chloe, a young escort hired by a suspicious wife, Catherine (Julianne Moore), to test her husband’s fidelity. What begins as a manipulation quickly evolves into a web of emotional and erotic entanglement, with Chloe becoming dangerously obsessed with the wife herself.

While the film offers glimpses into Chloe’s interiority and vulnerability, she remains fundamentally a cipher: sexually available, emotionally unstable, and ultimately lethal. Her youth, beauty, and bisexual allure are depicted as both tantalizing and treacherous, a femme fatale recast in millennial terms.

Unlike earlier iterations of the nymphet, Chloe is not a child or even particularly childlike, yet she is unmistakably cast as youthful and sexually uninhibited. She inhabits the adult male fantasy of the available, emotionally detached girl who exists to serve desire but harbors a hidden threat. However, in “Chloe,” the gaze shifts: the film is more about female fantasy and projection than male possession. Chloe is eroticized not only for the husband but increasingly for Catherine, who gazes at her with longing, jealousy, and fascination.

The girl becomes a site where middle-aged anxiety about fading desirability and lost vitality is projected. In Egoyan’s hands, Chloe is a postmodern nymphet: not a naive child but a constructed presence – crafted, consumed, and ultimately discarded. The film probes not just male desire, but also the feminine complicity in producing and perpetuating the fantasy of the desirable girl. Yet despite its female-centered perspective, “Chloe” never allows the titular character to become fully real. She is an erotic symbol, a narrative device, and emotional ghost, trapped not in a male gaze, but in a hall of feminine mirrors.

7. Stoker (2013): The Gothic Nymphet And Inherited Darkness

Park Chan-wook’s “Stoker” (2013) offers a haunting, stylized mutation of the nymphet archetype, reframed through the tropes of gothic cinema, family dysfunction, and inherited violence. Mia Wasikowska’s India Stoker is not overtly sexualized in the conventional nymphet sense; rather, she is quiet, hyper-observant, eerily self-contained, and emotionally distant. And yet, she carries the hallmarks of the trope: youthful beauty, unsettling allure, and a magnetic pull for older, predatory figures, especially her enigmatic uncle Charlie (Matthew Goode).

India is positioned as a mystery to be solved, not a voice to be heard. Her stillness, her silence, and her strangeness are all coded as seductive. Much like the traditional nymphet, she exists in the space between childhood and womanhood, both a daughter and a threat, a mourner and an accomplice. Her sexual awakening is inextricably bound to violence. When she witnesses Charlie commit murder, her response is not horror but curiosity. When she masturbates in the shower after burying a body, it is a moment of gothic perversion: death and desire converge, and the nymphet becomes a necrophilic archetype.

Unlike earlier depictions of the dangerous girl, India is not punished for her transformation. She embraces it. She kills, she seduces, she becomes a predator. But even this autonomy is complicated. India’s evolution is not a rebellion, it is an inheritance. She is shaped by a legacy of violence and psychosexual disturbance passed down through blood and proximity. Park’s camera aestheticizes her transformation, mirroring India’s internal awakening with formal elegance: sharp edits, lush color palettes, and symbolic sound design (notably, the heightened sound of eggs being cracked and shoes stepping on leaves).

Related to Stoker: Every Park Chan-wook Film Ranked

India, like Chloe, is not a simple victim of the male gaze. But she is still a figure produced by male authorship. While the film resists straightforward voyeurism, it remains invested in her image – her opacity, her sexuality, her transition into darkness. India is less a seductress than an unfolding threat: she is what happens when the nymphet refuses to be devoured and instead chooses to become monstrous on her own terms.

What unites these dangerous nymphets is not their autonomy, but how their danger is constructed within narrative limits. They may seduce, scheme, or kill, but always within a morality tale framework. The dangerous girl must be neutralized, punished, or rendered tragic by the film’s end. Her “power” is seductive but unsustainable. This reflects a cultural discomfort with female sexual agency, especially in the adolescent girl: she may briefly upend the order of things, but she cannot be allowed to live freely within it.

IV. Melancholy Fantasies: Liminal Longings and the Lost Nymphet

Within the wider phenomenon of nymphetmania in cinema, one recurring subgenre resists erotic spectacle or overt danger. These are films suffused with longing, stillness, and emotional ambiguity, where desire is muted, deferred, or unfulfilled. The girls in these stories are not seductresses or rebels, but ghostly presences, figures of missed connection or ungraspable innocence. The adult male gaze remains central, but instead of predation or projection, it is tinged with regret, grief, nostalgia, and often, emotional paralysis. In these melancholy fantasies, the nymphet figure functions less as an erotic object and more as an emblem of lost time, emotional stasis, or existential yearning.

These films often unfold in atmospheres of suspended time – hotel rooms, train stations, quiet houses – and are scored by minimalist music, muted lighting, and silences charged with emotion. Here, the male gaze mourns what it cannot – or should not – possess. Feminist criticism interrogates whether these films offer resistance to or merely a subtler aestheticization of patriarchal longing. Either way, they remain central to understanding how cinema transforms the girl into a medium for the adult’s unspoken ache, not just his lust.

8. Léon: The Professional (1994): Child Assassin, Adult Longing

Luc Besson’s “Léon: The Professional” (1994) is one of the most controversial examples of latent nymphet desire. While ostensibly a father-daughter-style bond between 12-year-old Mathilda (Natalie Portman) and a solitary, emotionally stunted hitman, Léon (Jean Reno), the director’s cut includes unsettling hints of mutual attraction. Though marketed as a stylized crime thriller, the film’s true thematic engine is the ambiguous emotional terrain between these two characters, a terrain that blends paternalism, erotic suggestion, and deep trauma.

What emerges is a cinematic object both seductive and unsettling, emblematic of a genre that flirts with the taboo under the guise of sentimentality and stylization. From her first appearance on screen, Mathilda is framed through a paradox: she is a child performing adulthood. Her cropped hair, cigarettes, red lips, and flirtatious expressions echo the coded language of classic Hollywood nymphets, remnants of “Lolita,” “Pretty Baby,” “Taxi Driver.”

However, Besson entwines her precocious sexuality with a heavy backstory of violence, parental neglect, and grief. This tragedy grants her an aura of maturity, making her erotic signals seem like a form of defense or performance rather than self-awareness.

Natalie Portman’s performance, extraordinarily nuanced for a debut role. imbues Mathilda with both fragility and bravado. The film’s visual grammar often undercuts her complexity by oscillating between the aesthetic of a muse and that of a child in crisis. Mathilda’s longing for Léon is portrayed not as delusion but as genuine emotional need. She tells him she’s in love with him. She tries to seduce him. And he resists, but tenderly. The film resists overtly sexualizing their relationship, Léon himself is emotionally and sexually arrested, but it cannot resist the aesthetic allure of their “inappropriate” closeness.

This is where the male gaze, in Laura Mulvey’s terms, becomes deeply entrenched. The camera, and by extension the audience, is repeatedly asked to consider Mathilda as “not quite” a child and “not yet” a woman. She occupies a liminal zone, part child soldier, part lonely orphan, part romantic companion, none of which fully belongs to her own agency. The result is a portrait of girlhood filtered through male loneliness and emotional repression, where the girl becomes a balm, a catalyst, and a mirror rather than a person.

9. Lost In Translation (2003): The Melancholy Nymphet

Sofia Coppola’s “Lost in Translation” stands as a defining example of the melancholy fantasy, reversing many of the usual dynamics of the nymphet trope. Set in the liminal spaces of Tokyo, anonymous hotel lobbies, karaoke bars, neon-lit streets, the film traces the unlikely emotional bond between Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson), a lonely young newlywed, and Bob Harris (Bill Murray), an ageing American actor adrift in ennui. Though their intimacy flirts with romantic or erotic undertones, Coppola consistently refuses to sexualize Charlotte in obvious ways. Instead, the girl becomes a kind of emotional proxy, someone through whom Bob confronts his own regrets, dissatisfaction, and aging masculinity.

Related Read: All Sofia Coppola Movies, Ranked

The fantasy here is not of possession, but of fleeting recognition: she sees him, not as a husband or a star, but as a vulnerable, alienated man. He sees in her not youth per se, but the possibility of connection unburdened by past or future. Charlotte, for her part, is not eroticized but drifted through. Her subjectivity is shaded in moments of solitude, looking out windows, wandering temples, lying in bed listening to others breathe.

Feminist critics have noted that while she is far more fleshed out than typical nymphet figures, she still serves largely as a mirror for male reflection, her emotional needs secondary to Bob’s crisis. Yet “Lost in Translation” allows for mutual tenderness, and in its final whispered goodbye, the fantasy is acknowledged, honoured, and released.

10. An Education (2009): The Nymphet Disillusioned

Lone Scherfig’s “An Education” chronicles the brief and transformative relationship between Jenny (Carey Mulligan), a precocious 16-year-old schoolgirl, and David (Peter Sarsgaard), a charming older man who draws her into a world of culture, glamour, and emotional duplicity. The film resists the aesthetics of seduction and instead stages their relationship as a slow disenchantment. David offers Jenny the fantasy of adulthood, Paris, cigarettes, intellectual banter, but what she ultimately receives is disillusionment.

The fantasy, in this case, is hers: of growing up fast, of skipping the drudgery of school for the pleasures of art and love. Yet the melancholy lies in how fully she believes it, and how utterly the illusion collapses. David’s attraction to Jenny is romanticized by neither the film nor the framing. Unlike “Lolita,” “An Education” is firmly aligned with the girl’s perspective. Her eventual heartbreak is not sexual but existential: she sees how deeply desire can be used to obscure truth. And yet, her intelligence, poise, and restraint prevent her from becoming a passive victim.

11. Palo Alto (2013): Soft Predation And The Fantasy Of Being Seen

Gia Coppola’s “Palo Alto,” based on James Franco’s short stories, is a drifting, melancholic exploration of adolescent ennui in a suburban Californian town. April (Emma Roberts), a sensitive and intelligent high school student, is seduced – gently, incrementally – by her much older soccer coach, Mr. B (Franco).

The film’s palette of pastels and shadows creates a dreamy haze through which predatory grooming is rendered not as crime or crisis, but as slow emotional erosion. April is emblematic of the melancholy nymphet: quiet, watchful, passive, and perpetually misunderstood. She is not eroticized in the lurid sense but filmed with an intimacy that centers her emotional unmooring.

Her relationship with Mr. B is marked not by passion, but by longing for validation, the slow realization of betrayal, and the dull ache of losing something she never truly chose. The male character, meanwhile, cloaks his predation in sensitivity, emphasizing how melancholy fantasies can be vehicles for emotional manipulation, cloaked in empathy rather than dominance. The power imbalance is not eroticized but quietly devastating. Coppola’s female gaze lends April a quiet interiority, allowing viewers to feel her absence of agency without needing to sensationalize her body.

V. Subversions and Reclamations: The Nymphet Tells Her Own Story

If the figure of the nymphet in cinema has traditionally served as a projection screen for adult male fantasy – whether erotic, melancholic, or punitive – then these films of the 21st century attempt something far more radical: they return voice, agency, and emotional truth to the girl. These works are not fantasies; they are narrative reclamations. Told almost exclusively through female perspectives (and often by women directors), these films unsettle the familiar patterns of gaze and control. They do not simply critique the adult man’s desire; they interrogate the narrative machinery that has historically rendered the girl invisible even in the telling of her own trauma.

In these films, the so-called “nymphet” is not a symbol of temptation or innocence lost. She is a thinking, feeling, narrating subject – often confused, vulnerable, and still forming, but never reducible to the roles others assign her. These are coming-of-age stories that are painfully aware of the power imbalances that shape young girls’ experiences of sex, love, and attention. But they also resist the temptation to flatten girlhood into either victimhood or agency.

Instead, they dwell in the gray areas – in memory, in ambiguity, in interiority. Crucially, these films are not just about what happened to the girl, but about how she remembers, narrates, and reframes what happened. The camera no longer peers at her; it aligns with her gaze. In doing so, these films restructure the cinematic grammar of girlhood, replacing spectacle with subjectivity and fantasy with reckoning.

12. Blue Car (2002): The Poetry Of Grooming And The Ghost Of Trust

Karen Moncrieff’s “Blue Car” (2002) stands out in the cinematic treatment of adolescent female subjectivity because of its quiet intensity and refusal to sensationalize the familiar but often mishandled trope of the “precocious girl” seduced by an older man. At the heart of the film is Megan (Agnes Bruckner), a sensitive, intelligent, and emotionally neglected teenager, whose talent for poetry draws the attention of her high school English teacher, Mr. Auster (David Strathairn). What begins as mentorship quickly evolves into a dynamic laced with emotional grooming, boundary-blurring intimacy, and covert desire, though the film avoids portraying these developments through conventional narrative beats of seduction or scandal.

The teacher, Mr. Auster, is not the archetypal predator. His power lies not in overt manipulation, but in performing care, listening to Megan’s poetry, encouraging her talent, offering her praise when her home life (a troubled mother, an absent father, and a tragic family rupture) offers little stability. In many ways, he represents the fantasy of the adult who finally sees the girl for who she is, a dangerous mirage that has been central to the cinematic construction of the nymphet. But “Blue Car” complicates this fantasy by showing how recognition can serve as a vector for exploitation, especially when layered over hierarchical power dynamics.

The sexual violation, when it comes, is not dramatized. It is quiet, sad, and irreparably disappointing. There is no erotic thrill, no redemptive trauma. Instead, there is a moment of collapse, a shattering of trust. Mr. Auster doesn’t force himself on Megan in the way a more conventional narrative might frame as rape. But that’s precisely what makes the betrayal more insidious: it reveals how emotional grooming masks itself as affection, and how easily adult power hides beneath the language of mentorship. Moncrieff allows her protagonist to feel deeply, to be smart and confused at once, and to emerge not broken, but wiser, more resolved. The film reclaims the narrative by refusing to eroticize either the girl or the abuse. Instead, it centers her betrayal of trust, allowing her voice through poetry to endure.

13. Fish Tank (2009): The Rebellious Nymphet

Andrea Arnold’s “Fish Tank” (2009) offers a piercingly intimate portrait of adolescence that pushes back against the eroticized myth of the nymphet. Mia (Katie Jarvis), a volatile 15-year-old growing up in an Essex housing estate, is not crafted to titillate or mystify. Instead, she is rendered with raw physicality and emotional immediacy – restless, confrontational, aching for something she cannot name. Her defiance and isolation are not signs of precocious seductiveness, but symptoms of social and emotional deprivation.

When her mother’s new boyfriend, Connor (Michael Fassbender), enters the household, the film begins to quietly track the asymmetrical dynamic that unfolds between the two. Connor appears warm, attentive, and playful, he encourages Mia’s interest in dance and offers her the approval she craves. But Arnold never lets the viewer forget the structural imbalance beneath their interactions. The camera, handheld and claustrophobic, stays close to Mia, aligning us with her experience rather than Connor’s gaze.

Also Read: All Andrea Arnold Movies Ranked

The power of “Fish Tank” lies in its refusal to aestheticize or moralize. The film exposes how working-class girls are often hyper-visible and hyper-vulnerable, perceived as both sexually available and emotionally disposable. But Mia is not a victim in the traditional cinematic sense – she is angry, impulsive, and yearning. Her sexuality, while present, is neither performative nor strategic. It is confused, raw, and at times self-sabotaging.

Arnold subverts the nymphet trope by stripping it of glamour and fantasy. There are no stylized seductions here, only a slow realization of betrayal, and a girl who must navigate her own messy selfhood. In doing so, “Fish Tank” asserts that desire does not equal consent, and visibility does not equal power. Mia’s story is not a fall from innocence, it is a fight for autonomy in a world that offers her none.

14. Daydream Nation (2010): The Postmodern Nymphet

Michael Goldbach’s “Daydream Nation” complicates the nymphet trope by making its heroine, Caroline Wexler (Kat Dennings), knowingly complicit in her own myth-making. She is a precocious teenager who relocates to a small, dead-end town after the death of her mother. When she begins a sexual relationship with her high school English teacher, Barry Anderson (Josh Lucas), while simultaneously toying with the affections of a shy classmate, Thurston (Reece Thompson), Caroline seems to enact the classic trope of the dangerous, sexually knowing girl.

But “Daydream Nation” is not interested in validating this narrative, it’s interested in dissecting it. Caroline is less a Lolita figure than a teenage girl aware of the cultural scripts imposed upon her, playing them out with deadpan cynicism. She knows she is being watched by peers, teachers, and the camera, and she manipulates this surveillance with a mix of boredom and defiance. Her sexuality is not innocent, nor is it deviant; it is a weapon against ennui, wielded in a world where all adults appear either predatory, ineffectual, or emotionally bankrupt.

Goldbach infuses the film with ironic detachment, monologues about romantic doom, literary references, and moody indie aesthetics. The result is a nymphet narrative refracted through a postmodern lens: hyper-aware, performative, and emotionally dissonant. But beneath the stylized detachment lies real loneliness, a longing for stability that the adult world fails to provide.

“Daydream Nation” ultimately resists placing Caroline within a binary of victim or femme fatale. Instead, it renders her as a girl exercising autonomy in a culture that gives her no space for vulnerability. It critiques the very construction of the nymphet by letting the girl play the part, and then showing the emotional void it leaves behind.

15. The Diary Of A Teenage Girl (2015): The Radical First-person Gaze

Marielle Heller’s “The Diary of a Teenage Girl” breaks open the genre by placing narrative control in the hands of its teenage protagonist, Minnie (Bel Powley). The film tracks her sexual relationship with her mother’s much older boyfriend Munroe (Alexander Skarsgård), but does so through Minnie’s own voice – her diary entries, voiceovers, and doodled animations that spill across the screen. This is not the nymphet as seen by the man, but the girl watching herself, trying to understand what she wants, what she feels, and what it all means.

Rather than vilify or eroticize Minnie, the film treats her experiences with tender, often painful nuance. Her longing is real; her pleasure and confusion coexist. The male character is not the center of moral drama, he is a weak man exploiting access. But the emotional arc belongs to Minnie, who reclaims herself through art, expression, and honest self-reflection. Diary is less about trauma than it is about emotional authorship. Heller’s female gaze turns the genre inside out, giving us a portrait of teenage desire that is neither shameful nor celebratory, just unflinchingly real.

16. The Tale (2018): The Unwriting Of The Nymphet

Jennifer Fox’s “The Tale” (2018) is not only a searing excavation of childhood sexual abuse, but also a profound meditation on the way language, memory, and storytelling shape, and often distort, how girls come to understand their own trauma. It dismantles the cultural fantasy of the “knowing girl” by revisiting the narrative from within, from the adult woman who once told herself a story of romance, only to later recognize it as abuse.

Jennifer (Laura Dern), a successful documentary filmmaker, begins to question the “love story” she wrote at age thirteen about a relationship with her much older riding coach, Bill (Jason Ritter), and his female accomplice, Mrs. G (Elizabeth Debicki). As Jennifer revisits her past, the film engages in a meta-narrative exercise, one that deconstructs the very architecture of the cinematic flashback. We first see her younger self as a confident, knowing teenager, echoing the nymphet figure as imagined in countless films: worldly, precocious, complicit in her own seduction.

Related: The Tale (2018) Movie Review: An Intensely Disturbing Story of Child Sexual Violation

The film’s most radical move is formal: it initially casts a teenager (Jessica Sarah Flaum) as young Jennifer, only to later replace her with a visibly younger, prepubescent actor (Isabelle Nélisse). This recasting becomes a powerful cinematic rupture, forcing both the protagonist and the viewer to confront the truth beneath the illusion of consent. Fox exposes how victims often survive by narrating their trauma as choice, a narrative structure reinforced by society’s tendency to sexualize girlhood and romanticize exploitation.

Rather than offer a voyeuristic account, “The Tale” privileges emotional and psychological complexity. Jennifer’s adult journey is not about recovering lost memories, but about reclaiming the right to interpret them differently. The abuse is not restaged for shock; it is reconstructed as emotional manipulation, complicity, and deep-rooted self-gaslighting. Fox’s feminist intervention lies in authorship. She refuses to let her younger self be mythologized into a nymphet. Instead, the film becomes an act of narrative resistance, an adult woman finally giving voice to the girl silenced by euphemism.

“The Tale” is not about innocence lost, but about truth reclaimed. It rewrites the trope of the seductive child by revealing its most enduring lie: that she ever knew what she was consenting to. As a contribution to the cinematic archive of girlhood, “The Tale” is singular. It unwrites the myth of the seductive child not through condemnation, but through reframing. It allows the adult woman to mourn the child she once misunderstood, and in doing so, it grants that child a retrospective subjectivity she was always denied.

Feminist Criticism and the Ethics of Looking

The figure of the nymphet is not born in isolation, it is nurtured by the cinematic apparatus itself. As Laura Mulvey argued in her foundational essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), mainstream film often serves the scopophilic and egotistical tendencies of the male spectator, casting women, and, disturbingly, underage girls, as objects to be looked at, fragmented, and consumed. The camera, under patriarchy, is not neutral. It is an extension of a desiring adult gaze that turns the girl into a spectacle.

In films like “Pretty Baby” (1978) and “American Beauty” (1999), this gaze is fully operational. Brooke Shields’ character is photographed like a living tableau, her nudity stylized to evoke both innocence and seduction. Similarly, the teenage Angela in “American Beauty” is framed through Lester’s longing eyes: petals rain on her naked body, not as she is, but as he imagines her. These scenes don’t simply show desire, they aestheticize and eroticize it, inviting the audience into complicity.

Feminist critics, including bell hooks, Carol J. Clover, and Linda Williams, have pointed out that such representations are never innocent. The nymphet trope displaces real girlhood, replacing it with a dangerously palatable fantasy that normalizes the sexualization of minors. It allows adult viewers, often men, to indulge in desire without confronting its ethical stakes.</p>

However, a wave of contemporary films by women directors, such as “Fish Tank” (Andrea Arnold), “The Tale” (Jennifer Fox), and “The Diary of a Teenage Girl” (Marielle Heller), actively resist this apparatus. These works recenter subjectivity, reclaiming the girl’s gaze and refusing the fantasy. In “Fish Tank,” the camera stays with Mia, often at eye level, unflinching in its commitment to her inner world. Her sexuality is present, but not exploited; it’s confused, reactive, and emotionally entangled.

Similarly, “The Tale” uses startling formal devices, like replacing the young actress mid-scene, to jolt viewers out of comfort and expose the fantasy of the “precocious girl” as a coping mechanism for trauma. Such films represent a feminist ethics of looking: one that refuses to fetishize or aestheticize girlhood, and instead insists on complexity, pain, and power. They are not only a response to Mulvey’s critique, but an evolution of it, a move from theory to cinematic practice.

Beyond the Gaze

The persistence of nymphetmania in cinema tells us less about actual girls and more about the adult anxieties projected onto them. From “Lolita” (1962, 1997) to “Poison Ivy” (1992), from “Palo Alto” (2013) to “Lost in Translation” (2003), the nymphet functions as a cipher, simultaneously seductive and tragic, angelic and dangerous, a symbol of lost youth, uncontainable chaos, or masculine regret. She is not a character, but a construction: a fantasy folded into the architecture of cinema itself.

Yet this fantasy is being slowly and crucially unraveled. In “Blue Car” (2002), the metaphor of poetry as grooming reveals how adult attention masquerades as mentorship. In “The Diary of a Teenage Girl” (2015), the girl narrates her own desire – awkward, messy, sometimes transgressive, but never aestheticized for external consumption. Even “Leon: The Professional” (1994), often criticized for its ambiguous dynamic, contains moments that expose the vulnerability beneath the nymphet trope.

To move forward, cinema must dismantle the optical pedestal on which the nymphet stands. It must find new languages for girlhood, ones that recognize its contradictions, its awkwardness, its rage and tenderness. Films like “The Tale” and “Molly Maxwell” do not tidy up the discomfort; they inhabit it, allowing girls to be seen not as erotic myths, but as complicated, half-formed people navigating the dangerous borderlands of coming of age. In dismantling the nymphet, these films do not merely challenge the male gaze. They propose a new way of seeing, one grounded in care, accountability, and the radical act of listening.