The re-emergence of Australian cinema in the ‘70s continued and flourished even further in the ‘80s, sticking with the number of trends that were commercially successful, but also introducing new ones as a result of a newer model for film production that was introduced. The prestigious art-house dramas and period pieces of the Australian New Wave in the ‘70s continued on through government funding, creating well-regarded films from this country like Gallipoli and Careful, He Might Hear You. They were even becoming more present and successful at renowned festivals, with Jack Thompson even winning the very first Best Supporting Actor award at Cannes in 1980 for Breaker Morant.

But these kinds of films weren’t as common as the cheaper Ozploitation films, which included all sorts of films belonging to the ‘80s most prominent genre – action. Not all films could be as great or have as elaborate a production as Mad Max 2 or Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, many of these action films were shonky dystopian films like Turkey Shoot and Dead-End Drive-In (both directed by the king of Ozploitation, Brian Trenchard-Smith), and car films for the Aussie rev-heads like Midnite Spares and Running on Empty. The reason for this influx in more low-brow and commercially viable content was due to a tax incentive introduced in October 1980 called 10BA, where its investors could claim 150% tax concessions on film financing.

And so, government financing become less prominent, as it was viewed as not being inclusive to these genre films – it was the public who were now bankrolling the films (though most of them made up of bankers and stock-brokers, not filmmakers), and even if these films didn’t make a profit at the box office, they didn’t even need to for investors to get their concession (and these folks were more interested in money than the films). Government funding was tight, with some films being made for as less than a million dollars, so crew members were sometimes badly paid. But under 10BA, even though more workers had to be paid (accountants, insurers, lawyers, brokers), there was still more money for these wages. Over the years, the number of films being made and the overall budget increased – 270 films were made in this decade, compared to 110 during the ‘70s, with $985 million spent on them in total.

The films thrived and were becoming more commercially successful than films of the ‘70s, especially as the Australian identity was becoming a hot commodity of itself, thanks to some internationally popular tourist ads featuring Paul Hogan, who soon afterward appeared in Crocodile Dundee. The cultural differences of this stereotypical larrikin in the big apple made it a huge unprecedented success, becoming for a long time the highest-grossing Australian film (dethroned by the Australian co-production Mad Max: Fury Road, though it remains the highest-grossing Australian film within its own country). It seemed overseas audiences were starting to enjoy the Australian New Wave and culture just as much as Australians themselves, with the cultural cringe evaporating and a more positive self-portrayal emerging in this decade than before.

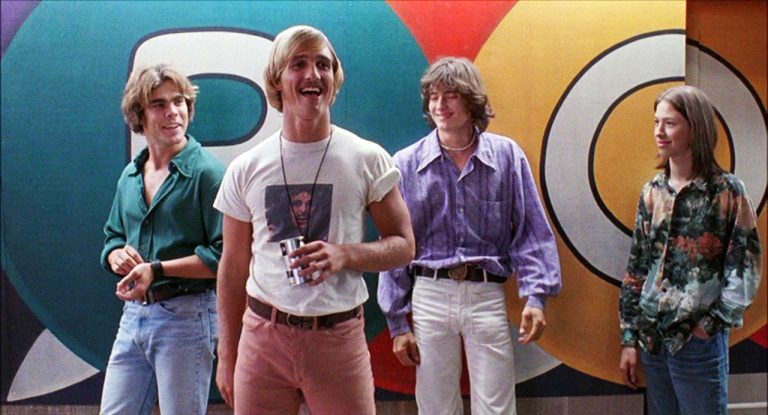

Many kinds of trends that began in the ‘70s flourished in the ‘80s mostly thanks to 10BA, such as the coming of age films (Puberty Blues, Starstruck, The Year My Voice Broke, Dogs in Space) that tapped into the youth market, as well as, conversely, tough-as-nails films that this country was adept as producing, namely a couple of prison films (Stir, Ghosts… of the Civil Dead), which showed the more authentic and brutal portrayal of prison life this side of Oz.

Similar to the Australian New Wave – Addiction and Film: A Complex History

But some of the trends from the ‘70s became lost. The ocker comedies were certainly dying out, the comedy genre instead replaced with slightly more mannered, but still slapstick affair (Malcolm, Young Einstein). And a few of the well-regarded Australian filmmakers of the ‘70s migrated to Hollywood in the ‘80s, actors like Mel Gibson (to star in the hugely popular Lethal Weapon) and directors like Bruce Beresford (directing Driving Miss Daisy), Peter Weir (directing Witness, The Mosquito Coast, and Dead Poets Society), Fred Schepesi (directing Roxanne), and Phillip Noyce (directing some popular action-thrillers in the ‘90s like Patriot Games and Clear and Present Danger), leaving Aussie cinema of this time for a new generation of newbies (Gillian Armstrong, Paul Cox, Jane Campion). There was also a reverse issue with American actors being placed in Australian films, lowering the number of acting jobs from its already low number, which caused concern in the Actor’s Equity Association (this issue most prevalent in Road Games, The Coca-Cola Kid, and A Cry in the Dark).

The 10BA scheme lost its popularity throughout the decade as the government became anxious about lost tax revenue through it. Its concession was lowered twice by treasurer Paul Keating, first in 1983, again in 1985, and by 1989, the return had become a 100% flat write-off.

In its resurgence in the ‘70s, the Australian new wave was admirable in how much it was able to suddenly emulate the quality of the films being released in the USA and Britain. But just like in these countries, this quality declined in the ‘80s, though still offered an exciting time for cinema and how it could reflect our cultures of this specific era.

![The Silence of the Lambs [1991]: The Voluptuous Death](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/silence-of-the-lambs-768x516.jpg)