“ [A]bhiman should be read not merely as wounded pride, not as whim or feminine pique…[the word] encapsulates what have been called ‘outlaw emotions’ such as rage, obstinacy, and protest,” editor and translator, Rimli Bhattacharya notes in the afterword to Binodini Dasi’s “My Story and My Life as an Actress,” published by Kali for Women. Bhattacharya clearly understood the perils of translating an emotion so conspicuously bedded in the culture of Bengal that it runs the risk of sliding into misapprehension. So cocooned is its existence, so vulnerable, that the slightest exposure seems like a threat to alter its fabric.

For the unversed, the word ‘abhiman’ in Sanskrit stands for pride and vanity. When used in Bengali, the grandeur of the word, which serves both to elevate and to awe, is released, and what is left is a somewhat elusive concept; a precise delicacy which is quite unmatched by that of any other feeling. Perhaps no other definition is more affecting than the one Sharmishtha Mohanty formulates in her book, ‘Extinctions.’ For Mohanty, the Bengali word stands for a “sense of self which has been wounded, and which cannot have, or does not want to have, any direct expression of that wound… Abhimaan assumes a childness, a kind of wound and love, or wounded love, of which only a vernacular is capable, a daily tenderness, a contiguous self, a searing need for the other.”

Yet, the emotion defeats precise and faithful translation in English. The experience of translating is tangled and often bewildering, as can be deduced from the ever-changing choice of words employed to capture its essence. The act of ‘obhiman’ (going by the exact pronunciation in Bengali) is at once a sacrosanct necessity, to sustain intimacy, and necessarily sacrosanct, standing for the essential purity in its expression.

There are swathes of cultural history preserved in rituals, gestures, and emotions such as abhiman, ignored by cultural imperialists. Gleaning insights from Mohanty’s vision of recording these fleeting, immaterial artifacts, now on the verge of extinction, I sometimes moon over finding a way to stunt the process of their progression into nothingness. I sometimes wonder what could be the reason for such a threat to their existence: has the investment in love and its circumambient gestures dwindled with time? Is it a result of the speedy assimilation of the local aspirations into a broader rubric of the ‘universal’?

In order to stymie the process, it is important to appraise the valuables and spread the word about their value. As “Lootera” re-released this week around the country, it was a reminder for me to witness how well it does the work of reviving the almost extinct and priceless sensibilities. Vikramaditya Motwane’s “Lootera” (2013) seems to be the most persuasive advocate of preserving such important intangible cultural relics: the gestures of love and quiet acts of heart that only the vernacular is privy to. Ironically, “Lootera” deals with the loss of tangible cultural artifacts of a zamindar. The story takes place in Bengal in the 1950s, where the passing of the Estates Acquisition Act indicates a disintegration of the zamindari system.

Zamindar Soumitra Roy Chaudhary, too myopic and attached to his long-lost glory, had erstwhile scotched the idea that the zamindars were standing at the brink of a ledge. As the flames reach close to home, he is forced to make sense of this newly modernizing state, which in all probability will not have a place for him. The arrival of Varun Srivastav, a young archaeologist, changes his life forever. The young man advises the zamindar to sell off the ancient relics he possesses. The state decrees the zamindar to forego the array of artifacts in his possession which would now be maintained at the museums.

Standing at the crossroads between choosing to lose it all to the government and losing it all in exchange for money on the advice of his new friend, the zamindar makes a tough call. On the other hand, the zamindar’s daughter, Pakhi, falls in love with Varun. Pakhi, who spiritedly embraces life, meets Varun right when her mortal sickness has fully revealed itself. The world of the Roy Chaudharys is turned upside down when Varun, along with his partner-in-crime, Dev, slips away with their loot.

As Pakhi and Varun slowly but surely forge a bond, the film employs close and intimate framing to meticulously record their expressive faces. The quiver of the eyebrow, the restrained narrowing of the eyes, smiles waxing and waning from the corners of the mouth– all become bearers of untranslatable and slippery emotions. At the dinner table scene, when Varun arrives at the palace for the first time, the mise-en-scene is such that it bolsters the communication of the half-said words. When the zamindar lightheartedly broaches the topic of Pakhi’s amateur writing skills to Varun, Pakhi is a little hesitant, but does not mind the conversation at all.

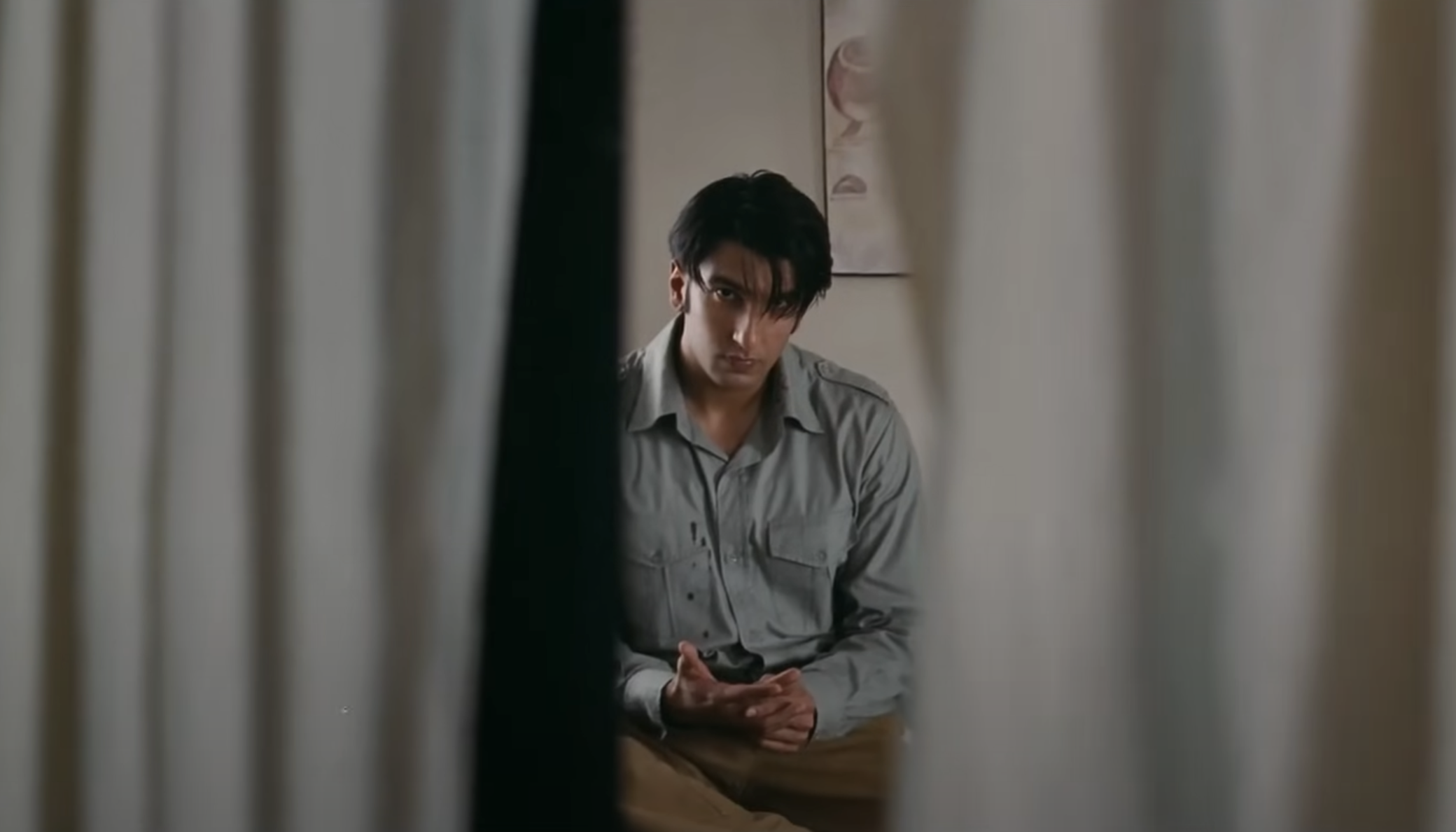

The seating arrangement around the table is such that Pakhi and Varun sit face to face, with a candelabrum almost blocking their view of each other. When Varun states his belief in her writing capability, it is a cue for Pakhi to express her satisfaction. There is not much to record on Varun’s face and, therefore, his face is in full view. On the other hand, the candelabrum blocks Pakhi’s face in such a scrupulous manner that only a sliver of her frontal face is visible through the two candles. She lifts her gaze for a moment, in response to Varun’s praise, and quickly looks down without looking directly at the speaker. It is the gesture of laaj, an expression of demureness but even the word itself is inadequate as it does little to express the undercurrent of unabashed flirtation.

Also Read: 7 Great Films on MUBI Hand-Picked by Vikramaditya Motwane

A little later, we see Pakhi proclaim that she wants to learn painting. Of course, this proclamation has a reason behind it. It is a way of professing her desire to get closer to Varun, albeit in a roundabout and tacit manner. Her ploy to rope in Varun as her in-house painting tutor is courageous and in line with the desires of her heart. A pervasive atmosphere and a series of evanescent gestures– playing on the variation of quick playful glances at each other and sustained scrutiny of the other– cement the fledgling romance.

An important moment in the film arrives when Varun stops appearing for his painting classes, as he realizes Pakhi’s feelings. Unaware of Varun’s motive and unable to bear the uncertainty, Pakhi arrives at the digging site to take him back. Pakhi tries to look for an answer to his absence, but Varun constantly stymies the process by holding back what she is looking for, both the answer and his reciprocation of her feelings.

Pakhi is desperate to know when he plans to come back, as evident from her way of uttering the days of the week in quick succession, accompanied by the fading of her smile to a more somber countenance. Her face darkens with anger. When she stomps her feet and demands what she imagines to be rightfully hers, Varun retracts and bursts her bubble. Pakhi grows wobbly when Varun calls the entire relationship a product of his stupidity. On Varun’s penultimate day, they have one last tryst. It is not until the Dehradun episode that we understand what might have conspired that night, through a flashback.

Cut to the Dehradun episode, Pakhi is now bitter and in no mood for love. As she prepares to finish her novel, the news of Varun’s reappearance disturbs her. A slew of memories make her job of writing and forgetting the past difficult. With the help of a flashback, we are transported back to that night before Varun was to disappear forever.

As Pakhi sits across the bed writing her novel silently, Varun tries to initiate a conversation. He asks her if there is a boy and a girl in her story and if the characters love each other. Pakhi’s answers to his questions come with a pause, hinting at her obvious inner wound. Varun gauges her emotional state and asks in whispers if she is angry, followed by the question if it is due to his imminent departure. Pakhi confirms his concern.

The stillness in her voice permeates the atmosphere of the room. The scene is a remarkable rendering of abhiman, of a soul that is tender from the hurt yet unbending. Her anger stems not only from her lover’s approaching departure but his inability “to catch those unrecorded gestures, those unsaid or half-said words, which form themselves, no more palpably than the shows of moths on the ceiling” (Virginia Woolf, “A Room of One’s Own”).

The songs set the tone as they serve both to conceal and to reveal the unencodable emotions. With hints of subcutaneous hope and despair all at once, the songs explain the fluidity and inconsistencies of feelings and emotions. While “Manmarziyan” is a lyrical extension of abhiman and gives a word to that feeling, where the obstinate heart weighed down by ‘outlaw emotions’ only finds solace in doing what it pleases, “Shikayatein” is the vivid account from the other side of the metaphorical ice melting inside his lover. The closest equivalent to abhiman in Hindi would be khafa hona or rooth jana (the latter even finds a place in the lyrics of the song ‘Sawaar Loon’). “Ankahee” on the other hand stands for the overarching theme of exploring the unspeakable.

I borrow the title of my essay from a line from Kamala Das’ poem ‘An Introduction.’ Tinkering with the words and turning the meaning on its head opens up a way to fit Pakhi’s world in it, due to her preoccupation with writing. I assume that her elite upbringing would give her enough exposure to a high-class English education, so she might be well-versed in all three languages, namely English, Bengali, and Hindi. Another loose conjecture is her ability to write in both Hindi and Bengali, as we see her writing letters to Varun in Hindi, even if it is simply a way to appropriate the Bengali story for a Hindi film. Lastly, the matters of heart are conceived and communicated through unspoken gestures with specific cultural inclinations. That is why, I believe, she loves and yearns in one.

In putting up a resistance against translation, Lootera’s glory lies in its disavowal of the forms of cultural imperialism and its whispered rebellion against plundering of the vernacular aspirations of the emerging nations by the colonial and imperial forces. Although the politics of “Lootera” largely remains underdeveloped, dealing with a social class that has eternally found itself on the wrong side of history, the quiet but passionate outpourings of love become radical acts in themselves as compensation.

I place “Lootera” in a fledgling constellation, where it shares the space with its only other traceable compatriot, Gulzar’s “Khushboo” (1975). In fact, when I watched “Khushboo” for the first time back during the pandemic, it was the first film to have fomented the idea of tracing the untranslatable, particularly the emotion of abhiman. The dialogue, the music, and the restrained expressions of Hema Malini’s Kusum and Jeetendra’s Vrindavan make it a reservoir of cultural history worth assessing.